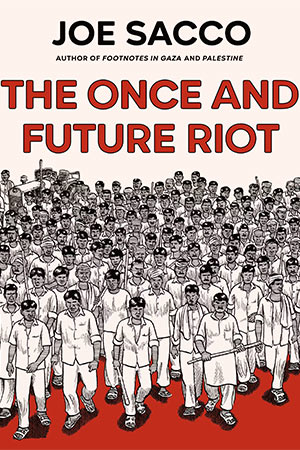

The Once and Future Riot by Joe Sacco

Metropolitan Books. 2025. 144 pages.

In September 2013 a riot raged through the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh, claiming over dozens of lives and injuring hundreds more. Journalist-cartoonist Joe Sacco arrived a year later to sort through the imbroglio. This is not a simple task for the casual observer of Indian history and politics. One must fathom the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan, which displaced some twelve million people and extirpated a million more. Also significant is the 1992 razing of the Babri Masjid mosque, which, like the Temple Mount in Old Jerusalem, sat upon a site in Uttar Pradesh considered sacred to both Muslims and Hindus. Subsequent protests triggered by that event killed thousands of people across the subcontinent. (In 2024 the Indian prime minister Narendra Modi consecrated the Hindu Ram Temple, constructed over the ruins of the Babri Masjid.) And a thousand other incidents, small and large, nonlethal and deadly, each of them significant in prolonging a fervent simmer in India’s cultural pot.

Sacco has made a career from casting his peppy, pen-and-ink style over ethnopolitics in the Balkans, Palestine, Iraq, and the Canadian North, among other locales, including India. His previous reporting from Uttar Pradesh on the Dalits, once called the “untouchable” caste, appeared in the French magazine XXI in 2011. His rendition of events in The Once and Future Riot, presented in his wacky-yet-grounded, sometimes graphic artwork, shows a local land-owning Hindu Jat minority feeling religiously victimized and politically oppressed by the local Muslim majority, who constitute the region’s agricultural labor. Elites feeling compelled into revenge against the very people they repress has many historical comparisons, as does the oppression of women, who in this case, as in many, receive the lion’s share of both blame and consequences for the conflagration. As Sacco writes, if you want to inflame any kind of riot, political, ethnic, or otherwise, “throw down female tinder before striking the match.” Elsewhere, he is told that “every incident of communal tension or riot in Western U.P. starts with a case of molestation.” Another shockingly candid statement comes from a Jat, who tells Sacco, “We don’t consider it a crime to murder somebody who is trying to encroach upon our land or trying to disturb our ladies.”

Such was the case here, when a Muslim man, accused of assaulting a young Jat woman, is killed by two Jat cousins. The two are then subsequently killed by a Muslim mob. The atmosphere thickens, and, egged on by various leaders and politicians on both sides, the violence spills out to neighboring villages, ensnaring thousands of people.

The reasons Sacco turned his gaze on this particular event are not discussed, but that, and the fact that the reporting in the book is over a decade old, hardly seem to matter; the intervening years have seen similar violence bloom across Uttar Pradesh from the same poisoned rootstock: in Dadri in 2015, in Bijnor in 2016, in Kanpur in 2022, in Sambhal and Bahraich in 2024. One local leader predicts that a “large-scale war will erupt at any time.”

“Do you believe in The People?” Sacco asks, pronouncing the thesis of the work. At one time, the question would have been about speaking truth to power; “The People” would have been the oppressed masses in search of equality and truth in opposition to some overwhelming force (say, “The Man”). Today, from India to America, “The People” has come to mean much the same as “Them,” a dark term imbued with menace. The Once and Future Riot is no doubt an astute look at India’s struggles, but it left me with little faith in any collection of people.

J. R. Patterson

Gladstone, Manitoba