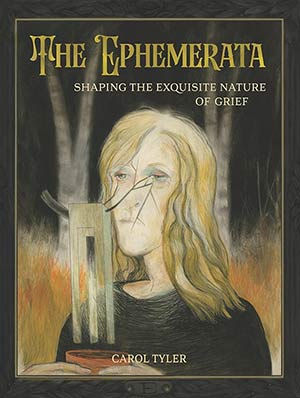

The Ephemerata: Shaping the Exquisite Nature of Grief by Carol Tyler

Fantagraphics Books. 2025. 232 pages.

Grief is common and yet unique—it happens to everyone and yet is never experienced in the same manner. Imagine how difficult it is to capture the experience of grieving in all its particulars and yet make it universal on the page. With great style and insight, this is what Carol Tyler manages to do, and do beautifully, in this graphic memoir.

It is not unusual to be averse to entering an arena of pain, or the “Realm of Cessation” as Tyler dubs it, and I was admittedly reluctant to enter the world of this book, even though Tyler’s illustrations were alluring. But I was ultimately persuaded by her early metaphors and images. Fallen large trees and a garden gone to seed lead to a single tombstone listing all the people she has lost too soon and too close together.

But this is not a mere list of loss. Nor is it a heady theological examination of death. Tyler hits hard as she draws a rather simple series of thought balloons containing the biggest questions that death invites us to ask about our own lives. “Did I matter? Did I do enough? Was I loved? Did I love well? Will I be remembered?” And this is all in preface to the real work as her journey continues into Griefville, where Tyler examines various styles of grieving, mourning, and caretaking. As she conducts a historical examination of grieving, she even creates an entire section around her great-grandmother Theola’s mourning bonnet, part of a tradition of grief apparel.

Throughout her description of her family’s history of loss in “The Bereft Are Left,” Tyler’s evocative black-and-white renderings of people, animals, and objects cross the boundary between actual and imaginary. Her emotions and explorations are the subject here, and the living Tyler struggles with the vagaries of domestic life as we all do. Being a daughter, sister, wife, mother, and dog owner provides her with a broad variety of losses to experience. With each, there is pain, empathy, anger, and love, and yet each has its own variety of absurd humor. There is even a page of euphemisms for death emerging from a pain bucket. The simple listing hits hard—too often we avoid the explicit statement of death, yet no one escapes it.

Tyler shows great vulnerability and pain in this memoir as she unpacks the difficult work of mourning and the difficult work of living. She must deal with an OCD husband, a daughter with a junkie boyfriend and thieving friends, a teaching job that is not secure, and the inability to cry and maybe to grieve because there is so much else to do just to keep afloat in her life. Each panel is chock-full of ideas and information. Some are eerie and some gorgeous. As she processes her grief, an intimacy between the reader and the text builds, and by the time she finds, for brief moments, some solace in nature, that breathing space is also a gift to the reader.

This is a rare and naked work in which Tyler offers a great deal of comfort and empathy in her depiction of the human condition.

Rita D. Jacobs

New York City