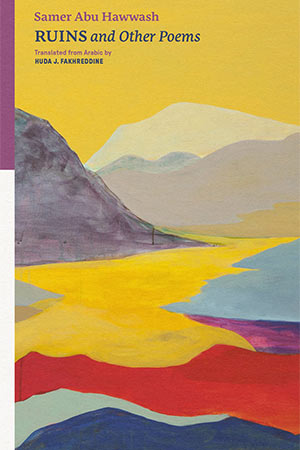

Ruins and Other Poems by Samer Abu Hawwash

World Poetry. 2025. 144 pages.

This bilingual edition of Samer Abu Hawwash’s Ruins and Other Poems, translated by Huda J. Fakhreddine, is a godsend for an anglophone reader such as myself. The volume has two main partitions: the three-part movement “Ruins” (belonging, one learns, to the qasida convention of Arabic poetry, classical and new), followed by a clutch of equally brilliant and moving poems, titled separately.

There are four dovetailing ways in which I would like to read this book, in brief, in order to display some of its patent riches. The collection evinces a kind of wisdom literature, and with its canny but melancholy play between presence and absence, it might also be read as a book that offers a kind of “dialectic of enlightenment,” moving between senses of irretrievable loss and sheer disenchantment and a kind of ghostly wish to reenchant a land forced into barrenness. Indeed, I noted in reading these translations of Abu Hawwash’s masterful verses echoes of both T. S. Eliot’s “The Hollow Men” and the infamous opening of his later Four Quartets. Thus the Eliot-esque notion of the “dissociation of sensibility” is one way of reading the movements of this book. Added to this, the infamy of Palestinian displacement—the relentless violence that has visited this people, then as now—sometimes finds its way into the verse with uncanny senses of infinite regress, absurd reductions, and, at times, reverse psychology. This book, for all its lyrical flair, is also a narrative, built and often driven by implacable tensions.

We read verses like “Whenever longing for him surges within me, / I’d grasp a handful of soil, / and learn something new about love” (“The Final City”) or, near the end of the book, where the poetic voice peels off the skin of a date to “reveal the gleaming stone at its heart,” we then read of how, “in the stone, I see all things, / past, present, and future” (“A Box of Dates on the Kitchen Table”), and we know we are in the presence of a kind of knowledge that is not just cognitive but derived from the saturation of sensory experience. A kind of prophetic blood-knowledge, where things become infused with spirit, after so many innocent lives have been spirited away. Indeed, on the subject of objects, the close of Ruins is titled “A Bench Remembers,” just as in the later piece, “From the River to the Sea,” we find a powerful list poem that manages to populate the reader’s imagination without use of a single verb. It feels as if, in so far as Palestinians are used and disposed of like things, not human beings, the poet’s (realistic) last resort must be to breathe new life into things, heart into the matter.

But to return to that late list of time-tenses (“past, present, and future”)—it is only one reference among others, as I see it, to the opening of Eliot’s “Burnt Norton,” burdened with the latter’s problematization of historical presence and absence. Indeed, the opening of “Ruins” starts with impactful senses of negation that can’t yet but live: “Morning didn’t come; / I wasn’t. // I awoke to the mirage of a tear.” This melancholy play is the result of a truly tragic impasse, the situation of Palestine, of Palestinians, very much an “impossible” situation if there ever was one: “these stones won’t speak / and they won’t go away.”

Such clear paradoxes are also made magically real in other places, too: “A dream erased a dream / and both were erased by yet another dream.” Or much later, “A soundtrack for a forgetting / that forgot / to be forgotten.” Such indications feel endemic to tragedy in its truest sense; a situation that cannot simply be resolved, made adequate, by the mind or by the body. This melancholy play works itself out in other ways in a kind of reverse psychology. Like the earlier unspeaking stones that yet won’t go away, the later poem “We Will Lose This War” seems to revel, with deeply sad and deeply riveted paradox, in the fact of loss. The eponymous line is repeated in a kind of reverse psychology aimed, it’s clear, to shame the killers—the Palestinians, as it were, the adults admonishing the murderous enemy like an impetuous child. This note of reverse psychology is also picked up in “It No Longer Matters if Anyone Loves Us,” another poem that displays a kind of perverse resignation which indicates, but with real finesse and moving flair, the sheer tipping point of Palestinian experience.

In all these ways, the impossible becomes, in some small and touching manner, possible. In “The Hollow Men,” Eliot’s notion of “dissociation” is imaged and lived out—the idea of inner and outer, mind and body, as sadly sundered in the modern world, what Max Weber famously discussed as “disenchantment.” I don’t want to say that this playful but deeply melancholy book somehow returns (to quote Abu Hawwash) to “an immortal wolf” its “primordial howl”; that somehow what Heaney called “the redress of poetry” actually happens in the wake of such horror. That would be too glib for such a serious-minded, tragic book. Still, for an English reader like myself, access to these skilled translations speaks volumes, and I am grateful for the gift.

Omar Sabbagh

Beirut