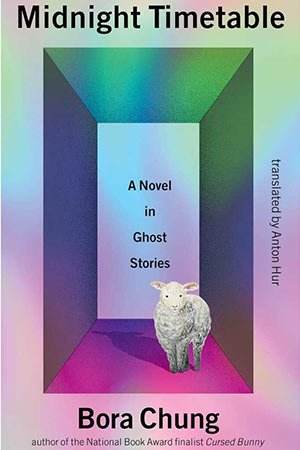

Midnight Timetable: A Novel in Ghost Stories by Bora Chung

Algonquin Books. 2025. 208 pages.

In Midnight Timetable, Bora Chung tells interconnected ghost stories that oscillate between chilling horror and fairy tale, weaving an unsettling narrative tapestry haunted by homunculi and handkerchiefs, by never-ending tunnels and by placid sheep mutilated by live scientific experimentation.

Chung introduces the reader to the Institute, a mysterious repository for haunted artifacts, through a first-person narrator who wanders the dim halls as a night-shift employee. This narrator hears ghost stories told by various denizens of the Institute: from an older, blind coworker; from the deputy director of the Institute; from a book found lying open in the employees’ lounge; and from the ghost of a cat who had been ritualistically sacrificed—and in the shadow of these patchwork tales, the Institute looms as an uncanny character itself.

Chung’s prose is unvarnished and all the more horrific for it. Her tales unspool quickly, quietly, with an irresistible momentum. One ghost story tells of a selfish brother to whom, in spite of his other siblings, his mother had been entirely devoted; she had coddled him and provided for his every need, and when she died, she left almost all her inheritance to him—everything but an embroidered handkerchief, which the brother coveted, but she had asked to be cremated with her. What follows is a story of midnight hauntings and intensifying obsession; a quintessential story of family. At the tale’s conclusion, Chung winks at the real-life horror belied by a ghost story like this: “And that’s when a completely different and much more ordinary type of family story began, one that is not a ghost story, but perhaps the scariest story of all.”

Indeed, throughout the novel, Chung uses ghost stories to address horrors very real and contemporary; among many, she discusses the scarring harms of conversion therapy and forced denial of queer identity, the far-reaching consequences of gambling addiction, and the all-too-common masculine violence of domestic abuse. The creeping tendrils of late-stage capitalism cannot be ignored throughout the entirety of the collection, too. In another story, a former employee is a paranormal influencer who livestreams his shifts at the Institute and steals an artifact to satisfy his viewers’ ravening desire for more content. Moreover, the very nature of the Institute—to hoard haunted artifacts, even for research purposes—implies the consumption mentality of institutions like the British Museum.

Interestingly, Chung includes an afterword in which she discusses her love for ghost stories and her motivations for writing Midnight Timetable. Much of the material for the novel comes from her life in and research about Korea. She compares the Institute to abandoned factories or hospitals haunted by toxins; she recounts that the invented medieval history from one of the ghost stories was inspired by the Korean history of the Kaya confederacy; and she describes how her fear of driving at night (and the series of tunnels in the Korean highway system) inspired the ghost story of a drive through a dark and eternal tunnel. That Chung’s horror fiction is grounded in her lived reality allows for verisimilitude to creep, creaturelike, into the supernatural.

What separates Chung’s horror writing from much of the mainstream, too, is that the forces in Midnight Timetable are not insidious but indifferent. The ghosts that haunt the stories do not seek out their victims for vengeance or evildoing; instead, horror finds the characters through flaws in the characters themselves—for instance, through the greed of the livestreamer and the covetousness of the brother—and thus Chung casts, not the ghosts as horrific, but the people with whom the ghosts interact. The human, in Chung’s novel, is the scariest thing.

Ultimately, Chung crafts in Midnight Timetable a tableau of the fearful and fantastical, the scary and the strange, and she wields the ghost story as a genre not just to scare but to destabilize the reader—and to ask the reader why they shudder and stumble through the hallways of the Institute. (Editorial note: Michelle Johnson’s Q&A with Chung appears in the March 2024 issue.)

Alex Crayon

University of Kansas