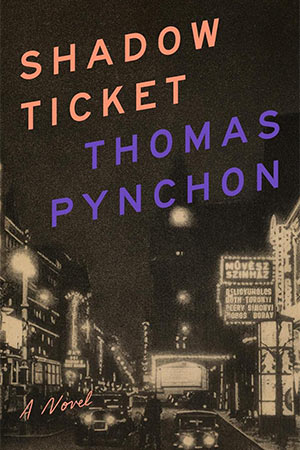

Shadow Ticket by Thomas Pynchon

Penguin Press. 2025. 304 pages.

Thomas Pynchon has broken his twelve-year quiet with a new detective novel in Shadow Ticket. As with his more recent works, it is a more accessible entry in an oeuvre that was once anything but. It kicks off in a Depression-era Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where money’s hard to come by, but “it seldom gets more serious than somebody stole somebody’s fish.” Prohibition has propelled cycles of escalation and abuse, creating bigger criminals and even bigger law enforcement, yet everyone appears to be drinking on the job, including those investigating bootlegger operations.

The protagonist this time around is Hicks McTaggart, a former strikebreaker turned private eye, and something of a prodigy on the dance floor. McTaggart, whose father has skipped town, spends early chapters seeking guidance between two surrogates—his boss Boynt Crosstown, uninterested in that role, and his uncle Detlef “Lefty” Flaschner, seemingly too preoccupied with the populist Hitler movement in Germany (a nominative irony for readers who follow reactionary politics). As the world around him grows stranger and more authoritarian, he finds a gradual and reflective direction in an auspicious encounter with a self-help seminar in comic strip form. He comes to believe that his heart isn’t in violence anymore, that maybe he’s lost a step, he isn’t the same “dirt stupid gorilla” people think he is. Where he’s unique among Pynchon’s gallery of capable fools as leading men, however, is that he’s the recovering adversary, a thug initially more at home in a James Ellroy novel who, these days, just wants to do a right thing and get the girl. Not everyone’s convinced, however, and attempts persist to revert or convert him.

He is captivated by the perpetually unavailable April Randazzo, a lounge singer who gigs at speakeasies, and their chemistry is teased out, then cut short. What he gets instead is a job he wants nothing to do with, namely, stopping the elopement of cheese heiress Daphne Airmont with a clarinet player in a swing band. McTaggart is pressured into the job by forces both known and unknown, including gangsters, his employers, and the feds, and he soon finds himself shanghaied aboard a Europe-bound ocean liner. It’s here that the narrative resets with an entirely new cast of characters as Hicks mixes with British spies, jewel thieves, Soviet-hunting assassins, golems, an incestuous father-daughter duo, fascist paramilitary bikers, cocaine-addled Interpol agents, and a mysterious “apportionist” who might know more about things than he lets on.

If the American part of Shadow Ticket is a fairly straightforward period noir, the European part’s closest tonal relative is perhaps Julio Cortázar’s 62: A Model Kit, with its ominous and magical settings, and, well . . . vampirism. This is also a book of black routes: Europe is full of smuggling checkpoints and ever-fluid borders, objects disappear from one location and appear in another at will, submarines emerge in the most unlikely of bodies, Nazi sleeper cells operate beneath innocuous Midwestern fronts, early Resistance members scout escape routes for European Jews, and throughout, the Second World War looms as an unstoppable apocalyptic event while invisible hands toil away in the background.

It’s an exhausted trope by now in many criticisms of Pynchon’s work, no matter its length or scope, to make unfavorable contrasts with Gravity’s Rainbow, so likely readers should know this book instead belongs to the class of his storytelling that includes The Crying of Lot 49, Inherent Vice, and Bleeding Edge, and among that lineup it holds up just fine. Shadow Ticket does read a bit thin in the sections transitioning between settings, which halts some momentum to reframe the story and almost feels like a stitching together of two different novels. Yet it still manages to stick the landing and function as a thoughtful, melancholy reflection of a moment where concerns of the 1930s have met a resurgence in this post-2015 world.

Where a direct comparison to Gravity’s Rainbow could be more appropriate is in the two books’ prescriptions for their times. For Tyrone Slothrop in pursuit of the rocket, the only way to win against an engineered system was to just not play. Here where that doom is almost certain, there are hints at a greater calling for Hicks McTaggart, one of vigilance and organizing, of a preparation for and finding purpose through resistance to what’s coming. And as one character says, “Whatever it is that’s just about to happen, once it’s over we’ll say, oh well, it’s history, should have seen it coming, and right now it’s all I can do to get on with my life.”

Michael Kazepis

Portland, Oregon