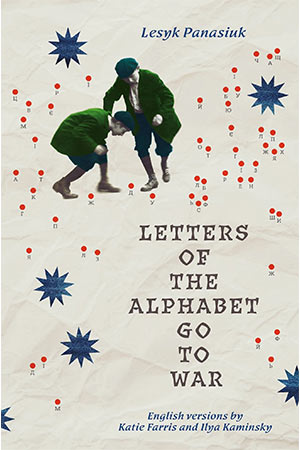

Letters of the Alphabet Go to War by Lesyk Panasiuk

Sarabande Books. 2026. 89 pages.

For anyone following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine for nearly four years now, the city of Bucha is one associated with brutality, atrocities, massacre, and war crimes. According to Ukrainian officials, the Russian military killed nearly five hundred people and committed over nine thousand war crimes. Lesyk Panasiuk’s Letters of the Alphabet Go to War, a bilingual collection, examines the necessity of language and poetry during the invasion’s apex. Words become living characters who witness and survive unspeakable, unforgettable devastation as language, lives, and a once-vibrant city rupture and break.

Poems like “Aubade” psychologically tug and blur the fine lines between surrealism and reality. The poem’s simple construction—three minimalist lines—reinforces how, frequently, poetry arrives at an unexpected moment and fills the present’s ever-widening gaps:

One morning I woke up

as a bomb

And flew headlong home.

The imagery is modernly, and terrifyingly, Kafkaesque. The separation of lines 2 and 3 contributes to the poem’s jarring surrealism. The poem’s brevity, nonetheless, personifies another horrifying reality faced by Ukrainians each and every day: how quickly war unravels lives and routines, and how drastically it reshapes an individual.

“October” possesses stark philosophical anecdotes that mirror the work in Yaryna Chornohuz’s dasein: in defence of presence. “October” poses questions like “is the world / ending?” It captures how war disrupts time, so that one day becomes unrecognizable from another: “and these days don’t end. / This October won’t end.” Again, Panasiuk adeptly renders war’s psychological and physical tolls into words: “No one will buy us in this shop. / I will be an open cash register. / You, a porcelain vase.” Hope transforms into “a duck” since, as the speaker observes, “ducks snatch our words / from foreign mouths.” The duck’s snatching of words from “foreign mouths” is symbolic of the reclamation of the Ukrainian language that swiftly occurred after the full-scale invasion began.

“Icon” is a brief, stark poem commenting on the transformation of Ukrainian families during the war. Drawing on the tradition of iconography in Ukrainian culture, Panasiuk reimagines the classic portrayal of an icon. “The whole earth is an icon,” the speaker states. Madonna holds the child, but “No father” exists with them. The speaker continues, asking if it is the “hole in our chests” to which a collective “we” pray. According to the speaker, the image “surprises no one” and “evokes no sympathy” because “It’s the traditional Ukrainian family.” What makes this particular poem even more stark is the minimal language and the simple line structures. The matter-of-fact tone implies not only a matter of acceptance. It also creates a sense of distance and dissonance from the rest of the world.

“Turbines of Hydroelectric Plants” serves as an image-laden reminder about the war’s ecocide. Trees poke through a river’s surface. Flooded villages become places “to which no one, no one, no one / returns—.” The speaker acknowledges, “How lucky are our dead: they do not see these streets.” The dead are spared seeing the transformation of “the geography of childhood,” a testament to the significance of landscape and nature for Ukrainians everywhere. Each day, according to the speaker, is transformed “into a day of the dead.” As the poem concludes, the lines taper from longer ones to shorter ones:

when you return from work turn on

the light:

darkness

how it

hesitates, before

leaving.

The personification of darkness, as well as the usage of the verb “hesitates,” echoes the blurring of time first portrayed in “October.” This stylistic and thematic combination also creates a permanence, an awareness that the war’s impacts will last for years, across many generations.

In its dissection of language and how it changes, adapts, and evolves during wartime, Letters of the Alphabet Go to War echoes Ostap Slyvynsky’s compilation A Ukrainian Dictionary of War. Thematically, in its analysis of atrocity and how individuals process brutality linguistically, it echoes Oleksandr Mykhed’s The Language of War. Despite these similarities, Lesyk Panasiuk offers the collection’s audience a visceral account of one of modern history’s darkest moments. (Editorial note: The collection’s translators, Katie Farris and Ilya Kaminsky, guest-edited the July 2022 Ukraine issue of WLT.)

Nicole Yurcaba

Southern New Hampshire University