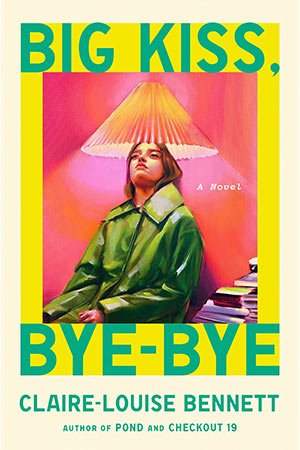

Big Kiss, Bye-Bye by Claire-Louise Bennett

Riverhead Books. 2025. 224 pages.

Claire-Louise Bennett is back, and she’s not pulling punches. In Big Kiss, Bye-Bye, Bennett’s third novel after Pond (2015) and Checkout 19 (2021), she plunges us into the raw, often agonizing disintegration of long-term partnerships. Her nameless protagonist, a woman navigating her thirties or forties, offers an intimate dissection of the moments that define—and destroy—our deepest connections.

The protagonist of Big Kiss has had to recently move from a house in the city to one in the deep countryside. Haunted by the memories of herself in that previous house and plagued by a sense of loss, the narrator thinks deeply about the houses in which we live our lives, how often some of us choose to move out of them, how some never really move out, ever, and the glib sentimentality that takes over some of us when we leave these houses. She muses: “Everything else went into storage yesterday. Something is loosened. The things that hold life in place have been lifted off and put away. I wonder about the rare people who never move. Who live on and on in the same house.” Going through her things when she comes across an old letter from a passing friend, she finds herself in the morass of more melancholy, more memories.

In this limbo, as her life seems to go on, the narrator is visited by memories of people as well, especially those she has left behind. Chief among them are those of her former lover, Xavier, whom she still loves. The writing style pulls the reader into the protagonist’s headspace as she relentlessly sifts through past and present partners, desperately searching for the elusive “why” behind having drifted apart. The novel is, much like Bennett’s previous novels, composed of long paragraphs and a heavy, often deliberately repetitive language and style that blends pervasive ennui and playful curiosity.

In Bennett’s hands, Big Kiss is a vital contribution to contemporary fiction, cementing her place at the forefront. While generally in form, worldview, and language, she continues to be inspired by her literary forerunners like Ann Quin, John Keats, and Samuel Beckett, Big Kiss is a novel that owes much to Annie Ernaux and Chris Kraus’s works.

We’ve all been through the pain of being cut off from a lover, friend, or a beloved relative after being connected for a long, long time. Bennett gets at the jugular of this ache. “Being out of touch with him does not sit well with me,” she writes, “because I begin to feel in my bones that I’m reneging upon a divine appointment. It is very important to me that I see this through.”

Pond and Checkout 19 remain two of the boldest, weirdly compelling novels of the last decade. Much like these two, Big Kiss also works to slow the reader down. Phrases are repeated, language deliberate. Bennett’s work demands to be read in a slow, attentive, but highly ruminative cadence that everyone around us seems to be ruing the death of these days. That said, I couldn’t stop reading the novel and finished it in a day.

This manner of writing about the inner workings of the brain and how it arrives at thoughts, beliefs, and emotions is what makes up the meat of Bennett’s work, putting her in the league of other maximalist writers such as Kraus, Ernaux, even Karl Ove Knausgaard, who has published her previous novels in Norwegian under the Pelikanen (Pelican) imprint, which he founded in 2010.

A heady, poetic impressionism rules Bennett’s hold over the language. Her prose comprises descriptions, repetitions, definitions, discoveries, and wildness in a way that has long been left out of contemporary literature. In defying formlessness, she works to create her own form; in engaging with the text this deeply, she makes her own language, grammar, and rules. This maximalist aesthetic casts a spell on the reader, even as there’s so little by way of plot. In her repetitions, she also verges on the territory so singularly created and tread by Italo Calvino in Invisible Cities, almost as if she’s charting through these novels the various invisible, intangible cities that reside within her.

Found objects, wordy obsessions, flowers, letters, and handwriting seem to be of special interest. A wicked sense of humor casts a languid pall over the text, binding us closer to the protagonist. This is not the kind of book one could listen to on audio. Big Kiss, just like Pond and Checkout 19, demands to be read, underlined, obsessed over in its print edition. You’ll be surprised at how much you’ll underline, thumb through, and scribble in the margins, making a diary of your own inside these pages. A wild, untamed annotation to her work—perhaps the only way her books should be enjoyed.

Anandi Mishra

Gothenburg, Sweden