Forgotten: Searching for Palestine’s Hidden Places and Lost Memorials by Raja Shehadeh & Penny Johnson

Other Press. 2025. 240 pages.

If you know anything about the history of Israel/Palestine, you know that one of the first things that happened after the creation of the new state of Israel was the effort to “de-Arabize” Palestine. This was part of the long-term Zionist vision that sustained the narrative of “a land without a people for a people without a land.” Although “de-Arabization” began even before 1948, it is a prevailing feature of Israel’s occupation in the West Bank today; one need only see recent pictures of Gaza’s flattened landscape to know that Israel’s ultimate goal is to make Gaza not only uninhabitable for its Palestinian residents but also to erase the continuous history of Palestinian life there.

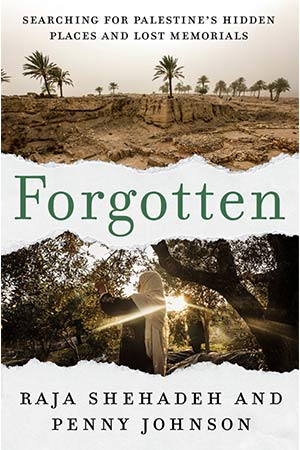

The new book Forgotten: Searching for Palestine’s Hidden Places and Lost Memorials, written by Palestinian writer Raja Shehadeh and West Bank academic Penny Johnson, explores their effort to recuperate, document, and contextualize Palestinian hidden places and lost memorials in painstaking detail in the face of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank. Reading this book now, after two years of continuous Israeli bombing and destruction in Gaza, only adds greater poignancy to the narrative; Shehadeh and Johnson show rather than tell us how instrumental it is for Israel to overlook the diverse history of cultural exchange, travel, human contact, and, yes, conquest of Palestine that existed outside and over a much longer span of history than modern Zionism.

To reinforce the state and biblical narratives, Israelis must engage in a willful forgetting and, ultimately, an omnipresent erasure that serves the interests of Israeli identity and the state. Of course, Forgotten gives a sense of the magnitude of the previous losses of the first Nakba—of monuments, buildings, historic sites—and what portends for the future of Palestinian memory in the post-1948 period. The authors began this project in the first days of 2022, chronicling those losses and erasures that were the result of the Nakba and Israel’s denial of it. And while those losses are immeasurable, they are dwarfed by what has transpired since October 2023, when Israel has dropped an estimated 85,000 to 100,000 tons of explosives on the Gaza Strip—the result of which has made life in Gaza altogether uninhabitable, never mind its wholesale erasures of homes, hospitals, schools, universities, mosques, churches, memorials, and even public records.

The opening sentence of the book declares exactly what the book delivers: “a search for hidden or neglected memorials and places in historic Palestine, now Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories,” and an “investigation into what they might tell us about the land the people who have lived, and are living, on our small slip of earth between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River.” This quest is undertaken by Shehadeh, Johnson, and their photographer guide and friend, Bassam. At nearly every turn, they must confront not only the emotions that are triggered by viewing the abandoned and forgotten memorials and places of the past but the active attempts to erase Palestinian life from the land in the moment in which they are writing.

In one of the early scenes where they are heading to the Palestinian town of Hawara near the entrance to Nablus, the team describes scenes of the Israeli settlement highways (Highway 60) that have been built on confiscated Palestinian land. One of these tunnel roads, built exclusively for Israeli settlers, is emblematic of the greater encroachment of settlements in ever greater numbers on Palestinian land in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. “Since our visit, Hawara residents had endured a pogrom—the term used by the Israeli army commander of the area—when on February 23, 2023, some four hundred settlers, mainly from the nearby Israeli settlement of Har Bracha (Hebrew for ‘hill of blessing’), went on a five-hour late-night rampage of revenge for two settlers shot and killed by Palestinian militants. The Palestinian was killed and some hundredt Hawara residents were injured, including four who were left in serious condition. At least fifteen houses were burned, one with the family still inside.” The book documents the ongoing effects of settlement-building as well as settler violence (one can now view this openly on social media), indeed of Israeli state violence, and the impossibility of attaining justice for both Palestinian residents and their ownership over the land; ultimately, this book seeks to not only recuperate the omissions of history but the omissions and erasures made by the media headlines that fail to account for what daily life is like for those living under Israeli military occupation.

Interspersed between the individual locations that the authors seek out—sometimes successfully, sometimes thwarted by fences and Israeli checkpoints—Shehadeh and Johnson describe in rich and elegant prose the significance of some of the places that memorialize, for example, fallen Egyptian soldiers or the remains of a wall surrounding the great Bronze Age city of Tell Balata. In their meditations on loss and in their efforts at recuperation, one can feel the concentric losses of Palestinian history that the world is experiencing today. This book feels all the more essential and urgent as the rich and long history of Palestine and the contemporary existence of Palestinian people are threatened daily by Israeli state and settler violence, which makes the Nakba not an event of the past but an ongoing and very much present reality.

Persis Karim

Berkeley, California