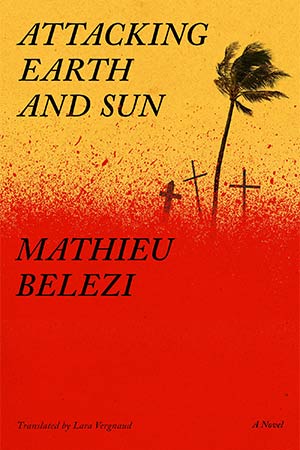

Attacking Earth and Sun by Mathieu Belezi

Other Press. 2025. 144 pages.

Though fictitious, Attacking Earth and Sun reads like personal memoirs from the early days of France’s occupation of Algeria during the mid-nineteenth century. With alternating chapters of agonized desperation and frenzied brutality, Mathieu Belezi hypnotically relates two colonizing perspectives, drawing from his meticulous historical research to present the past with unflinching honesty and raw emotion.

The first perspective of this short novel comes from Séraphine, a wife and mother who has left poverty in France with her family in the hope of a better life in France’s new territorial acquisition among five hundred other colonists. Surviving the dangerous journey, the family discovers a reality estranged from the promises given by the French government. Apart from the comfortable administrative class, the newly arrived colonists find themselves in an isolated slapdash village, vulnerable to the elements and a defensive native population. A cholera epidemic soon complicates their bleak hopes of securing a foothold in this hostile, still foreign land.

The second perspective comes from an unnamed soldier of the French army, one of an indistinguishable many devoted to their captain and to the annihilation of the Algerian “barbarians” who refuse complete submission to the colonial authority. Tasked with putting down resistance, the army’s bloodlust and savagery quickly escalate into a hypocritical devastation of the native people and land, fueled by murder, rape, and flames.

Though coming from these two different perspectives in alternation, Belezi composes the text of Attacking Earth and Sun with a unified structure and shared stylistic elements. From what I can tell, the English translation by Lara Vergnaud retains the absence of periods (full stops) in the original French text and only uses capital letters in dialogue, for proper names, and the pronoun “I.” Each sentence is given its own paragraph, however, providing the text with easy readability and comprehensibility even with its deviations from the norm.

I wept

I couldn’t help but weep when we arrived and saw the land that would need working

holy Mary mother of God

days and days of travel, along the Seine and the Saone, and then the Rhone on boats flat as the palm of your hand and drawn by horses that took their sweet time, believe you me, while at every lock the men raced to the inns to gorge themselves on food and wine as we poor women used the pause to wash the linens not to mention the children, days and days I’m telling you, until at last we could make out the sea, the sea and its dazzling light that beckoned like a beacon over the port of Marseille

holy Mary mother of God

With such stream-of-consciousness text, Belezi brings the horrified, frantic reality of the characters’ lives to the reader with maximal empathy. Vergnaud’s translation effectively captures the poetic and melodic flow of the language that gives warmth and beauty to a novel whose plot is utterly cold and harsh. Long lines that flit from one panicked thought to another are broken up by the repetition of such phrases as the “holy Mary mother of God” refrain, which punctuate the text like a liturgical rite of response. Though immediately obvious through the Roman Catholic point of view of Séraphine, such repetition appears equally in the secular perspective of the soldier, with his cultlike devotion to the captain and his mantra: “you’re no angels!”

Along with the juxtaposition of sublime text over a nihilistic plot, what I find most impressive about Attacking Earth and Sun is how effectively Belezi and Vergnaud make the two perspectives unified yet unique. Readers are apt to read Séraphine more sympathetically than the soldier, with Séraphine a relatively powerless and ignorant victim of her circumstances and the solider a willing powerholder and eager participant in atrocities. Though both grim, there’s a relative gentleness to the “Hands of Toil” chapters devoted to Séraphine compared to the cruel “Bloodbath” chapters of the soldier. Indeed, the titles to the respective chapter perspectives say it all.

In the end, Belezi reveals something universal for the characters of the slim Attacking Earth and Sun, whether innocent, evil, oppressed, or in power. Everyone is damaged. Far from being a system of betterment, benevolence, or pioneering opportunity, colonization is revealed to be a dehumanizing and pestilent social institution that provides nothing more than an illusion of power and control, with a high cost in bodies and souls.

Daniel P. Haeusser

Canisius College