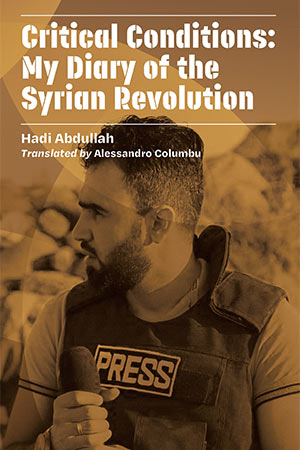

Critical Conditions: My Diary of the Syrian Revolution, by Hadi Abdullah

DoppelHouse Press. 2025. 278 pages.

Some books arrive as testimonies, others as warnings. Hadi Abdullah’s Critical Conditions: My Diary of the Syrian Revolution is both: the Syrian nurse-turned-journalist delivers a memoir of rare urgency and moral clarity. Translated with care and political nuance by Alessandro Columbu, the book spans thirteen harrowing years—from 2011 to 2024—chronicling the brutal arc of the Syrian uprising as well as the interior life of a man whose camera became a weapon against erasure.

The memoir unfolds in impressionistic bursts—vignettes drawn from demonstrations, secret radio transmissions, field hospitals, funerals, and front lines. Abudullah’s writing, shaped by the immediacy of lived trauma, resists easy classification, belonging almost everywhere. It is part frontline diary, part oral history, and part literary testimony. These short chapters, often poetic and aphoristic, are dispatches from inside the storm.

The book is tripartite. Part 1 (2011–2014) documents the euphoric and idealistic early days of the revolution. In this section, we witness Hadi as a young nursing student in Homs, swept up in protests sparked by the children of Daraa scrawling “You’re next, doctor!” on a school wall. He soon transforms from student to citizen journalist, forming a grassroots media team with his first cameraman, the principled and joyful Tarad al-Zuhouri. Part 2 (2015–2019) descends into darkness: Russian airstrikes, chemical attacks, regime advances, and the collapse of opposition bastions. Hadi is imprisoned, injured in an assassination attempt, and mourns the deaths of close friends, including Tarad and Khaled Issa. Khaled’s murder, in particular, casts a long shadow. The two had made a pact; if one of them died, the other would carry on the mission. Part 3 (2019–2024) is composed of WhatsApp voice memos sent by Hadi to Columbu as the regime began to collapse. These entries, intimate and unfiltered, carry a double temporality—reportage and retrospective at once. On December 8, 2024, the regime falls. Hadi returns to al-Qusayr, now a bombed-out shell. He does not gloat. Instead, he whispers to his parents: “We will rebuild it. We will rebuild the whole town.”

One of the memoir’s greatest strengths is its balance of moral clarity and emotional nuance. Abdullah is uncompromising in his denunciations of Assad’s regime and extremist groups like Jabhat al-Nusra and ISIS. When Jabhat al-Nusra arrests his colleagues Ra’ed Fares and Hamoud Junayd for allegedly “hating Islam,” he tells them: “You’re just like the Assad regime, like ISIS, like any other brutal regime in the world. . . . I will expose you.” His revolutionary ethos—dignity, justice, nonsectarianism—remains undiluted.

The memoir is filled with recurring motifs, each carrying layered meanings. The jasmine flower appears repeatedly as a symbol of Damascus and peaceful resistance, even when its fragrance is overshadowed by the smoke of barrel bombs. Another significant motif is the Arabic word ʿayn, which means “eye” and is used affectionately to address friends. This holds both literal and symbolic significance, as the regime’s snipers often aimed for the eyes of protesters. In this context, where eyes are targeted, the word becomes a powerful act of resistance, a gesture of intimacy that reclaims humanity.

Equally memorable are the small, luminous details: a protest banner spotted on live TV; a mother guarding her son’s secrets; the taste of dust after a bombing. These moments do not merely add texture; they constitute the emotional core of the revolution. Where official histories list casualty numbers, Abdullah names the martyrs. His writing refuses abstraction.

The translator’s introduction is a thoughtful accompaniment. Opening with Antonio Gramsci’s line, “The old world is dying and the new world struggles to be born; now is the time of monsters,” Columbu positions the memoir within a wider framework of insurgent hope and catastrophic transition.

In many ways, Critical Conditions lends itself to a growing canon of Syrian literature born of the revolution, including Samar Yazbek’s A Woman in the Crossfire, Yassin al-Haj Saleh’s The Impossible Revolution, and Khaled Khalifa’s Death Is Hard Work. Yet while these texts—along with others like Wendy Pearlman’s We Crossed a Bridge and It Trembled and The Home I Worked to Make—come from exile, Hadi’s memoir is written from within, collapsing the distance between witness and participant, writer and revolutionary.

As editor Michael Beard aptly writes in the foreword, this is “history seen from the inside.” It is also a love letter to those who did not survive, a requiem for the disappeared, and a declaration of narrative sovereignty. Abdullah writes not to elevate himself but to archive the unarchivable—the laughter of Khaled, the wit of Ra’ed, the resilience of protesters who carried banners through clouds of tear gas.

In the aftermath of the regime’s fall, Critical Conditions does not indulge in victory. Instead, it offers memory as resistance. Even in ruins, even in exile, Hadi Abdullah reminds us that revolutions are fought not only with weapons but with words.

Ibrahim Fawzy is an Egyptian literary translator and writer whose work centers on memory, displacement, and the politics of language.

Ibrahim Fawzy is an Egyptian literary translator and writer whose work centers on memory, displacement, and the politics of language.