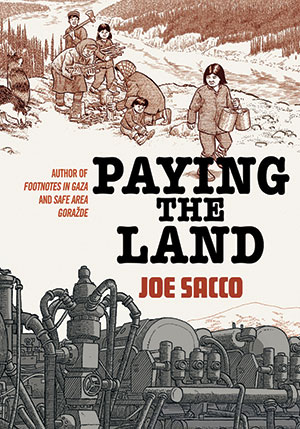

Paying the Land by Joe Sacco

New York. Metropolitan Books. 2020. 264 pages.

New York. Metropolitan Books. 2020. 264 pages.

WITH JOE SACCO having garnered fame for reporting from war-torn locales of the Gaza Strip, the Balkans, and the Russian Caucasus, a book from the Canadian North might, at first glance, suggest a change in heart for the cartoon-journalist. But, as always, stories form the bedrock of his latest book, Paying the Land. Though the setting may be safer, Sacco reveals it to be a place no less fractious than those other war zones.

The book itself is the story of the First Nation people, the Dené, who live on the resource-rich land of the Mackenzie River valley in Canada’s Northwest Territories. The land is key to their traditional identity. As one activist tells him, “Without the land we cannot be Dené. Without the land we don’t have integrity. Without the land we are a weak people. Ownership is not how we look at the land.”

But mightier forces believed otherwise and conspired to change the course of the Dené’s future. Canada’s first prime minister, John Macdonald, set the precedent for change, decreeing that regardless of their education, so long as indigenous children remained within the influence of their parents, they would merely be “a savage who can read and write.” The resulting government crusade to move children into reeducation camps (which ended only in the 1990s) ushered in decades of trauma and pain.

Working behind survivors’ recollections, Sacco’s depictions of the residential-school experience are horrific in their repetition, their detail, their silence. Beyond that, they go a long way in explaining the loss of language and culture and the subsequent loss of community reliance in the culture that once thrived on it.

Those who remain are divided as to how to move forward. For some, turning to the precious resources that lie in the ground could be the salvation of the Dené. But tying an entire culture’s future to the price of a barrel of oil is too risky for others. As one Dené elder tells Sacco, “The government pulled people out of the bush to put their children in schools, and they graduated from their independence [on] the land into a money-based economy with no jobs.”

Sacco provides no answers in what is his finest, most layered work to date. But one thing stands evident, as a young activist points out: the “defined system[s] of colonization and governance are not there for us to succeed as land users, they’re there for capitalism to succeed.”

J. R. Patterson

Gladstone, Manitoba