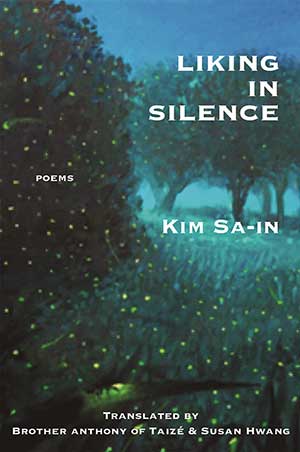

Liking in Silence by Kim Sa-in

Buffalo, New York. White Pine Press. 2019. 120 pages.

Buffalo, New York. White Pine Press. 2019. 120 pages.

IN THE PREFACE to Liking in Silence, eminent Korean poet Kim Sa-in tells his readers that “[growing] up through an era of developmentalism and authoritarianism” has caused his poems to take up positions of “compassion and sympathy.” Indeed, texts in this book are suffused with water cannons and homelessness, old lovers, temples, death, grief, and drunkenness. These are capacious works taking in minuscule details of the everyday’s casual and causal contexts. When noticing a little toe poking through a sock, the poet sees “a million years of human history”; when watching a butterfly, Kim wonders “[h]ow far on earth / are you going.” When “a prematurely dead leaf drops stealthily,” he exclaims, “Thanks! / Really, this is something to be grateful for.”

These poems are attuned to the existential, and Kim speaks as if reflexively from a position of profound humility. The poet casts a gently vigilant gaze across the dramas around him (both human and otherwise), watching as “good days drift away, like a lost scarlet hairpin . . . Before we know it, dust settles on every windowpane and everything blurs.” Within these inevitabilities, he announces a clear role for poetry: “I have no intention of blaming anyone after all this time. / We are beginning to resemble the thing / we have long been dreaming of together in harmony.”

The tones in Liking in Silence are alertly calm, and this book watches multitudes intersect, minutiae endlessly explored for implication. A “tiny weed stands in [his] way,” and in the next poem, Kim seems so bewildered by mundane beauty that he wonders whether the fragrance of an acacia tree “come[s] from a distant star.” When not opening onto such interconnections, the poems seem to yearn toward it (in “harvested fields / flocks of birds are indifferent”), and, on the next page, the poet wants to know to “whom shall I speak about sorrow?” This book is suffused with such questions, democratically asked, and the poet only seldomly ventures answers. Perhaps this is the point, for Kim’s assiduous inquiries sustain not only a poetics but also an engaged humanity. His imagistic immersions are moral and know all too well how full the world is of random forces, which can change the course of a life in an instant.

The poet refuses to avert his gaze from scenes of poverty, misery, tragedy, and so many poems in this book investigate betrayals and enmities where “a knife can be hidden behind a smile.” In one poem Kim is caused to ask, “does life still have manners?” And yet the poems are as if reflexively positive, and this from a poet who since the late 1970s “has been imprisoned three times and [has] had to hide with pseudonyms from the oppressive regimes.” As he asserts, manifold suffering may be “easier to endure if I say: ‘It’s all learning.’” These impeccable poems serve “even in some small way all the unconsidered things in the world,” and Kim’s oceanic calm is exemplary. Liking in Silence shows how, no matter what (or despite everything), tranquility can be possible.

Dan Disney

Sogang University (Seoul)