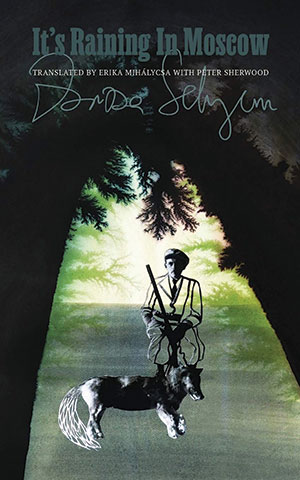

It’s Raining in Moscow by Zsuzsa Selyem

New York. Contra Mundum Press. 2020. 147 pages.

New York. Contra Mundum Press. 2020. 147 pages.

IT’S RAINING IN MOSCOW is the first collection of stories in English by Zsuzsa Selyem, a well-known Transylvanian Hungarian author and critic (see WLT, Nov. 2016 and Autumn 2019). It focuses on the history of one family, the Beczásys, who had Armenian ancestors but put down strong roots in a Transylvanian village; in the center stands István Beczásy, agricultural expert and gentleman farmer (the author’s maternal grandfather), with chapters devoted to Bandy, the easygoing uncle from Budapest, and Zina (Juci), István’s elegant polyglot wife. The stories span over forty years of Communist rule in Romania, starting with a hunt arranged for some “important comrades” in 1947 and ending with a “Circus Finale” of 1989, the year of change. In between, you have humorous and horrifying stories of the vicissitudes and sufferings of the Beczásys, first in forced resettlement, then jail, and also at forced labor on the Danube Canal.

Selyem’s narrative technique is skillful, vaguely postmodern, occasionally veering toward the absurd. While we can be involved in the story of Lux, Beczásy’s dog, and try and sympathize with the pathetic cat shivering in the gales at the Danube Canal (the place of István’s interment), it is hard to accept the far-too-intelligent comments of the bedbug in Beczásy’s cell in “Patissserie 1952.” It is one thing to regard prisoners of the secret police simply as “nutriments” but another (from a tiny bedbug’s point of view?) to treat the vile modus operandi of the Securitate in some detail. The experiences of Lux, the clever and faithful dog, recall Tibor Déry’s ”Niki,” a Hungarian novel about a dog, which achieved international fame in the years following 1956.

Most of these stories are imbued with humor and understanding for the main character, who is much more interested in the quality of the soil or the propects of harvest than ideologies or in the loudly proclaimed and economically disastrous ”class-struggle.” Quite a few of the methods used during the Communist period were not indigenous to Romania but copied from Soviet (NKVD-approved) procedures. The puzzling title of Selyem’s collection alludes to this, quoting an anecdote (not, I think, known to many Western readers), about Ana Pauker, one of the top Stalinist leaders before Gheorghiu: “Why does Pauker walk with an open umbrella in blazing sunshine in Bucharest? Well, it is raining in Moscow.”

It’s Raining in Moscow is skillfully translated by the Transylvanian scholar Erika Mihálycsa and London-based Peter Sherwood, but on the basis of their usage of certain idioms, the book is clearly intended for the transatlantic market. It also includes a multilingual index of place-names for the reader lost in the bewildering European territorial changes of the twentieth century.

George Gömöri

London