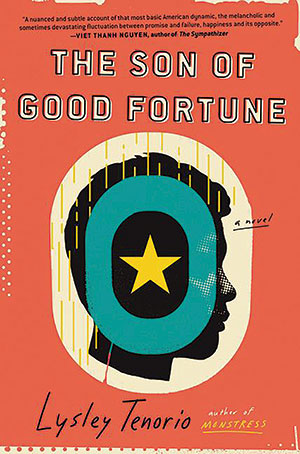

The Son of Good Fortune by Lysley Tenorio

New York. Ecco. 2020. 290 pages.

New York. Ecco. 2020. 290 pages.

MAXIMA IS A washed-up Filipino action hero, trained in the deadliest of martial arts, but her days of fighting bad guys on the big screen are over. They ended twenty years earlier when she got pregnant and bought a one-way ticket to California. Now she charms nice guys on the small screen of her computer. The Son of Good Fortune, by Lysley Tenorio, tells the story of her son, Excel, as he evolves from teenager to adult, despite still looking like a child. Maxima and Excel live TNT—tago ng tago, “hiding and hiding”—as undocumented immigrants. Maxima’s martial-arts instructor, Joker, takes them into his modest apartment in Colma, just ten miles south of San Francisco.

Aside from two short trips to visit San Francisco as a kid, Excel’s world is limited to a few-mile radius around the La Villa Aurelia apartment complex where they live. When Excel meets a wandering young woman, Sab, he leaves the only home he knows and moves to Hello City, an experimental community in the California desert with her. In Hello City, Excel encounters a truth-telling owl, entrepreneurial hippies, retirees, and artists. Excel’s journey beyond the tight radius of life around his apartment is confusing and strange. As he recounts, “Arrival—was utterly foreign to him—he’d never really come from somewhere else before.”

Tenorio could not have predicted how relevant the chaos caused by the coronavirus pandemic of 2020 would make Excel’s trials of belonging, family, and home. For example, the novel explores questions about place and identity by examining the intimacy born of talking via screens, something 2020 has made us more familiar with than ever. It draws our attention to the way you can get closer to someone else’s face via video chat than you ever would in person, how you can stare, maybe not directly into their eyes, but examine their face, see into their home. At the same time, it reminds us of how we can feel so distant from each other even when sequestered away in the same small apartment. It explores the difficulty of being together as well as the hurt caused by leaving. Today, amidst the awareness of social connection and distance caused by a pandemic, the questions The Son of Good Fortune raises about community, identity, and place seem prescient. How does home locate or separate us now in a world where we are all capable of being connected or disconnected through screens, cables, and wire?

The Son of Good Fortune, Excel’s coming-of-age story, is poignant, hilarious at times, and heroic, even if the characters do not fit any hero stereotypes. Tenorio has a rare ability to capture bizarre but believable details like the daily routines of The Pie Who Loved Me, the detective-themed children’s pizzeria where Excel works monitoring the ball pit, cleaning toilets, and dressing up as Sloth the Sleuth. But it is Tenorio’s characters—ordinary and struggling but also unforgettable and haunting—that make the book a treasure. I dreamt of Excel and Maxima while reading the book, and for days after, my subconscious mind worried about their fate. Tenorio renders the everyday difficulties and choices of his characters in a way that recalls Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist masterpiece, The Bicycle Thief; in both cases the day-to-day challenges of ordinary workers struggling to survive and the way their fate is intertwined with luck and circumstances is unforgettable. Just as I remember Bruno, the boy pumping gas in De Sica’s film, I won’t be able to forget Excel hunting for a child’s lost tooth in the colorful ball pit of The Pie.

Without romance or melodrama, Tenorio renders Excel’s growth and maturity, his search for agency, his desire only to have the power to help someone else, a triumph both for Excel and the power of kindness and caring.

Stephanie Pilat

University of Oklahoma