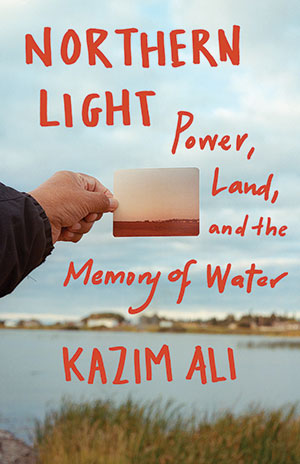

Northern Light: Power, Land, and the Memory of Water by Kazim Ali

Minneapolis. Milkweed Editions. 2021. 200 pages.

Minneapolis. Milkweed Editions. 2021. 200 pages.

ON A NIGHT WHEN icy winds blew south off Lake Erie and shook the windows of Kazim Ali’s house in Oberlin, he remembered the Canadian winters of his youth and searched online for images of Jenpeg—the company town he’d lived in as a child. He finds little online about Jenpeg. It’s mostly gone, the modest network of residential homes for employees at the hydroelectric dam under construction on the Nelson River.

Other regional headlines piqued his interest instead. In Cross Lake, across the waters from Jenpeg and home to the First Nations Pimicikamak community, Chief Cathy Merrick had made headlines for serving eviction papers to Manitoba electric-utility giant Manitoba Hydro. Chief Merrick had contended that Manitoba Hydro, the province of Manitoba, and the federal government of Canada had not fulfilled their agreements in the Northern Flood Agreement, the 1977 treaty with five northern Bands under which Manitoba Hydro received easement rights to build the generating station. The Jenpeg Generating Station and the former town of Jenpeg where Ali lived were on Pimicikamak sovereign territory. Now, the dam his father had built was negatively impacting the Pimicikamak’s community and changing the biodiversity of their unceded lands and waters.

He read more: last winter, in Cross Lake, six young people between the ages of fifteen and eighteen had died by suicide in the space of two months. The Pimicikamak had declared a mental-health emergency, and, Ali writes, “the Elders in the community had gathered and performed a sacred ceremony calling on the spirits of the land and water to assist.”

In the weeks that followed, he couldn’t get Cross Lake out of his mind. The contemporary concerns in Cross Lake alarmed him and recalled the years that Ali, who is queer, Muslim, and the child of South Asian migrants, had spent traveling through the Palestinian territory in the West Bank teaching yoga and training yoga teachers. “I’d seen the impacts of occupation and political disenfranchisement up close,” Ali writes, and “the sociopolitical impacts of colonialism.” He wonders about his own family’s complicity in the dam that his father had worked on at the Jenpeg Generating Station. Reflecting on his family’s culpability in the dam beside his work in Palestine, Ali probes his own blind spots: “What made it possible for me to recognize the damage that colonialism far from home had wrought when I’d thought so little about the damage that I myself might have played a role in?”

What rights and responsibilities does “being from” a place saddle a person with? Ali, who has called many places home, asks: What does it mean to have a point of origin, a community to belong to, or several? With richly layered questions about place, home, colonialism, complicity, indigenous sovereignty, and his own activism and childhood memories in mind, Ali emailed Chief Cathy Merrick. He wanted to learn more about the daily social and environmental issues facing Cross Lake and told Merrick he’d grown up in Jenpeg. Her email back was brief but generous: “It is wonderful that you would reflect on your childhood. You are more than welcome to visit our Nation.”

Shortly thereafter, he boarded a plane and flew north.

Northern Light is a journey story that troubles the maxim “You can never go home again.” Ali does go home, but that home, the town of Jenpeg, is gone to boreal forests growing back in the glow of Manitoba Hydro. He goes home to humble himself before the Pimicikamak community on whose ancestral lands he’d lived, unbeknownst to him, as a child. Ali returns to listen and be in dialogue with a community that has long called the waterways of the Nelson River their home. He returns to look closer and more tenderly at a place that is and is not familiar, that does and does not belong to him.

His journey to Cross Lake is full of connections, burgeoning friendships, late-night hockey games, brunches honoring mothers, and school visits. Ali is a kind and attentive listener, curious, always a warm presence on the page. Always eager for more.

What do we each owe to the places we call home, and what can we give back to them, and to each other? Ali’s ethical imaginary is as finely honed and illuminating as his prose. “We belong to the places of our earliest griefs, belong to where we left our dead, and belong to places where those younger than us were born.” What a privilege his fine book is, what a joy to spend a week in Cross Lake beside Ali. Returning home, he observes: “Places do not belong to us. We belong to them.”

Kathryn Savage

Tulsa, Oklahoma