The Eucalyptus Grove (an excerpt)

I’ve seen it more than once: the raised axe

swings and chops into the last remnant;

Lying still in the dirt

is the moving, glowing crown.

– Rahel, Eucalyptus

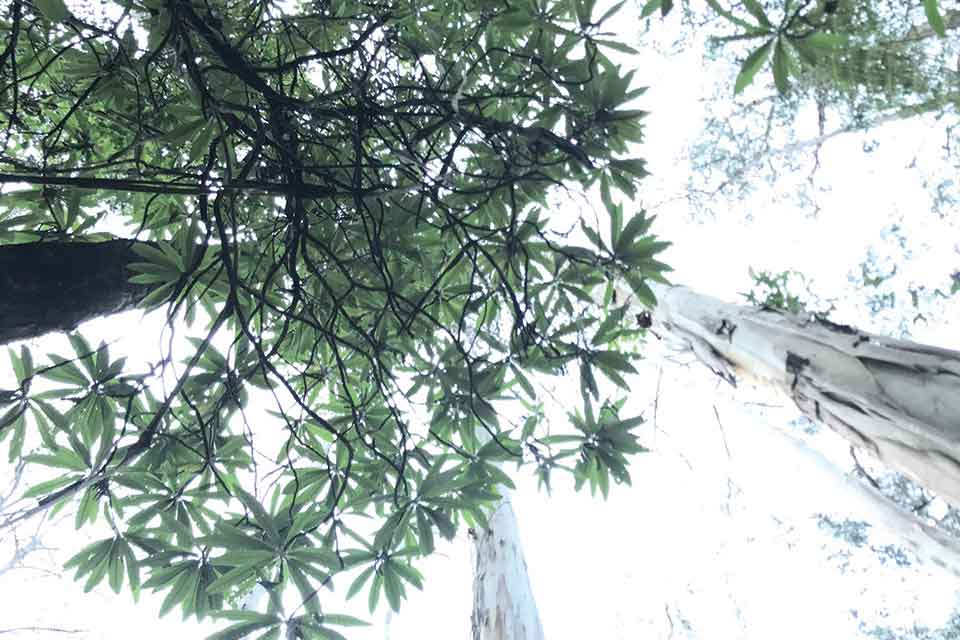

The gray-green tops of the eucalyptus trees were the first thing Avi saw every year as the sluggish Fishermen’s Island ferry slowed down at the entrance to the port. Searching for the treetops, his eyes flitted over the green horizon, spotted gray by the rooftops of the sprawling vacation homes, and didn’t come to rest until finding them, as strange and familiar as always. Seemingly, the eucalyptus trees didn’t belong on the island: they were unusually tall and towered over the local brush; their leaves had a faded, arid look; the gray dirt of the grove was also different from the island’s dark, fertile soil. And yet, though the trees were utterly alien to the landscape and climate of Fishermen’s Island, nothing symbolized his bond to the place better, a bond that began over thirty years earlier when he and his first wife, Odelia, bought a house on the island and started spending their summers there.

But something was different about the view this year, and Avi’s visual search went awry. His gaze sped back and forth over the horizon, going faster and faster, searching in vain for the silvery-greenish stain of the grove. They weren’t there, they were gone. His eucalyptus trees had disappeared as if they had been swallowed by the earth, as if they had never been there. Avi was gripped by an eerie, intense unease. The sudden disappearance of the trees disrupted the festive sense of anticipation that filled him every year when the ferry drew close to Fishermen’s Island, separating him from his daily worries and routine concerns and carrying him to this calm, wonderful place for which he had such intimate feelings, even though it was so different from the landscapes of his distant childhood. His large hands gripped the damp rail tightly. He leaned over and continued to scan the horizon as if believing he could will the lost trees back into existence. The ferry blew its loud, metallic foghorn, alerting the crew at the pier of its imminent arrival. He had to go find Lauren and the kid, who were probably still amusing themselves by throwing bits of bread to the seagulls that hovered over the ferry, hoping for scraps, and take them to the car down in the hold. Avi detached himself from the handrail, gazed for the last time at where the eucalyptus trees were supposed to be, and went to look for his young wife and their three-year-old, Alex.

Avi’s eucalyptus trees had disappeared as if they had been swallowed by the earth, as if they had never been there.

The short drive to the house was spent in unpleasant silence.

He was distracted. He forgot to slow down before stop signs and had to make abrupt stops that made the car shudder, the bottles of wine in the back clink in protest, and Lauren to flare up in annoyance.

Upon the long-awaited arrival at the house, the usual festive feeling was still absent. Avi clambered out of the car, stretched his legs, and looked around, but he wasn’t suffused with strange joy as he usually was; he didn’t take in the salty sea air with relish; he didn’t ramble busily between the rooms of the house, checking the taps and fixtures to make sure they were working properly; he didn’t even unload the wine from the trunk of the car, a crateful that he had selected with great care and pleasure at his wine shop in Princeton, a cherished annual rite forced upon him by the puritanical laws preserved since Prohibition in many counties and towns in the state of Massachusetts, including wide swaths of Fishermen’s Island where the sale of alcoholic beverages was completely banned. He helped the still-scowling Lauren with the suitcases, muttered a confused excuse that even he didn’t comprehend, got back in the car, and drove in the direction of the main road, not knowing where he was going and why.

Driving by himself without the oppression of Lauren’s angry presence in the car, Avi started to feel a little better. He drove slowly and took in the view, trying to connect the beautiful landscape with his pleasant memories and with the pressing longing he felt every year at the onset of spring, which made him take off from Princeton on the very first day of summer break for the island. Thirty years! Thirty-two, to be exact. He and Odelia were invited by the department head of political science at Rutgers to spend the weekend at his vacation home on the island. It was their first year in the United States. They weren’t planning to emigrate, not at all. They were so young, kids, really, and weren’t thinking too hard about the future. Avi was singled out early for his promise in his field and was invited to Rutgers even before he formally completed his PhD, provoking the envy of his fellow students and even some junior faculty. It started as a yearlong postdoc, but Avi’s abilities distinguished him in America just as they did in Israel. His contract was extended by two years, a rarity at the time, and from there things continued, as they often do, at an almost dizzying pace: an offer from the department to fill a position that had unexpectedly opened up; early tenure; and, finally, his successful negotiation with Princeton, which had kept its eye on the young, promising Israeli scholar since the publication of his first book, which garnered widespread attention. It all happened so fast: the journal articles, their first child, their first home in Princeton, the second child, the second book, the full professorship. They didn’t have time to breathe, to digest, to clearly think things through. When was the exact moment that they made the decision to stay in America indefinitely? Was there even such a moment? The unease that prickled him onboard the ferry returned, and Avi pressed on the gas. No, there was no such moment, not really. Things didn’t work out like that in life, only in movies and books.

All Avi caught were broken pieces: the whitewashed wall of the old synagogue in the moshav; yellowing fields in summer; spindly palm trees, their beards of gray spathes giving them a senescent look; the patch of eucalyptus trees by the grocery store.

They visited every year. Almost every year. Sometimes Odelia took the kids to Israel while Avi stayed home in Princeton to teach the summer program or to finish some important article. Unlike Odelia, it took Avi no time at all to feel at ease on the East Coast. For some reason, the sizes, the shapes, the very scale of it made him feel right at home. It was odd, but Avi never stopped to think about it. He attempted to dredge his memory for the landscapes of his childhood but failed to bring them up to the surface. All he caught were broken pieces: the whitewashed wall of the old synagogue in the moshav; yellowing fields in summer; spindly palm trees, their beards of gray spathes giving them a senescent look; the patch of eucalyptus trees by the grocery store. Eucalyptus! Roused from his revery, Avi pulled to the side of the road, turned off the engine, and looked around him in wonder. As if of its own volition, the car had brought him to the place where until recently his eucalyptus trees grew. He stepped out of the car and walked a little unsteadily toward the grove. There was nothing there. The trees had been cut down, every last one. The patch of earth was leveled and the soil compacted to make it ready for the construction of a new house. Shaken, he looked at the lot, its borders marked by wood beams and colored flags. Maybe he was at the wrong place? It wasn’t as if he deliberately sought out the place. He was driving almost absentmindedly. But the consolation of that thought was brief. He knew the spot well, much better than he was ready to admit. He had driven there dozens of times before, sometimes taking a longer route just so he could see the gray-green trees and the gray dirt for a few minutes longer. The grove was gone. The trees were gone and would never be coming back. That was that.

Translation from the Hebrew