Apocalyptic Scenarios and Inner Worlds: A Conversation with Gloria Susana Esquivel

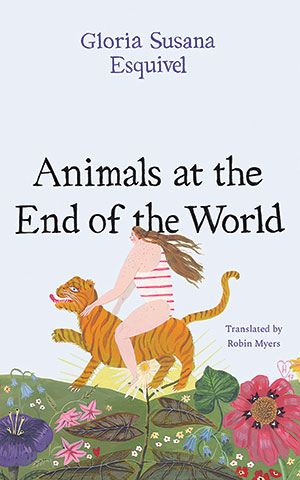

Poet and fiction writer Gloria Susana Esquivel has been quickly positioned in the spotlight of recent Latin American literature. The University of Texas Press recently published Animals at the End of the World, the English translation of her first novel. The novel follows Ines, a seven-year-old girl, in the weeks that precede the apocalyptic end of the world. Together with María, the housemaid’s daughter, she ventures through the labyrinthine space of her grandparents’ house and, in the process, witnesses the aggressive, sorrowful, and desolate world of the adults who surround her. Outside, the political violence of Colombia in the 1990s threatens to intrude into her world, and slowly but surely, Ines’s innocent world starts to crumble. What emerges from the destruction is a scathed and wounded animal that is both elusive and fierce. The novel is a tour de force that stands out as the voice of a generation, offering shrewd insights into a country, an era, and a cohort marked forever.

Esquivel is also the host of Colombia’s most renowned feminist podcast, Womansplaining, and a leading voice in cultural and feminist debates. À propos of the recent translation of her novel into English (translated by Robin Myers), we sat down to chat about her book, her podcast, and being a woman writer in Colombia.

Camilo Jaramillo: You chose an interesting narrator for Animals at the End of the World: the voice of a child through the memory of the protagonist, an adult. Can you speak of the difficulties of working with this voice?

Gloria Susana Esquivel: The book is narrated from the voice of a woman remembering her childhood. When I was doing research for the novel, I read many books written from the voices of children, and I thought it was very hard to achieve that kind of voice in a credible way. The girl is about to be seven years old and learning how to read and write, and it is very hard to translate that process into writing. The way children form sentences is very different from the ways an adult would. That would have exceeded my talent, and it was not what I was after. That’s why I decided that it was going to be narrated by the voice of a woman who remembered her childhood. What happens, though, is that this voice gets so immersed in these memories that she is able to bring a very genuine child’s perspective of the world, and that adult voice seems to merge with the voice of a child.

Jaramillo: When you were writing the memories and experiences of a child, did you rely on your own experiences as a kid, or was it, rather, a blank canvas for you to explore with freedom and creativity?

Esquivel: Memory and imagination can’t really be separated; they are linked. I did need to go into my memories, but not to bring out facts and events, or how things happened, but more to re-create the ambiences, smells, and the general feel of my childhood house. For example, I wanted to unearth how I perceived its light or its dimensions. I wanted to go back to that place and try to perceive the world like a child. Once I was there, in a set of sensations, then the story unfolded. And the story is all fictional and invented.

Jaramillo: The novel goes back to childhood as an attempt to go back to the origins of something. What is the character Ines trying to find in her past?

Esquivel: When I was creating Ines’s voice, I tried to imagine a woman who was going to psychoanalytic therapy. Although this does not appear in the story, this structure became a key feature for me. What Ines is doing, by telling those memories to herself again, is trying to understand why the adults that surrounded her acted like they did and, in the process, trying to understand how these adults affected her. More than trying to find something, she’s trying to make sense of her past. But memories are elusive, and, ultimately, her attempts are revealed as a fickle exercise: memories have a contingent meaning and are volatile.

Jaramillo: As the reader delves into the story, multiple meanings about animals and animality start to emerge. This can be seen, for example, in the title of the book, the games children play, the metaphors the adults are described with, etc. Can you talk about the drive to include animality in the text?

Esquivel: One of the references I had while writing the novel was Kipling’s The Jungle Book and the Disney film. It’s the story of a kid who is raised by a bear and a panther. The bear embodies many of the values and traits attributed to mothers, and the panther embodies the opposite side, the father. Ultimately, these animals face an important question: to raise him as an animal or as a human. I thought this was fascinating. I wanted to illuminate those instances of being raised that were not guided by rational principles. Much of our behavior is just animal behavior. In the end we are all animals, but animals that have language. Many times, the characters in the novel are driven, above all, by their instincts, without really realizing how this affects the protagonist.

Additionally, there is nothing more instinctive and animal than that which comes out when you are surrounded by your family. Family ties are animal ties, and that’s the place where our consciousness is molded. Every time we are with our family, particularly, our unconscious is on the surface. In other words, I wanted to explore the animality of a family. So, overall, I thought that animals and their behavior were the way to talk about those familial relationships I was interested in exploring, those instances where rationality was not the dominating principle.

There is nothing more instinctive and animal than that which comes out when you are surrounded by your family.

Jaramillo: Violence is omnipresent in the story. Sometimes it’s domestic violence, but other times it’s the violence that happens outside, generated by the political unrest of the 1990s and the war on drugs. This violence has been an important topic in Colombia’s literature. Did you feel it was your responsibility, as a Colombian writer, to address this topic?

Esquivel: It is true that all Colombian writers, at one point or another, have represented violence in their texts. It is my impression that some generations ago, this was done directly by representing that violence or some of its aftermath: they would represent partisanship and its aggressions or make clear references to the armed conflict. I believe young Colombian writers are doing what can be described as “elaborations” on that violence. These do not necessarily spring from specific acts of political violence. Instead, they are more about what it means to coexist and inhabit a violent reality.

Esquivel: It is true that all Colombian writers, at one point or another, have represented violence in their texts. It is my impression that some generations ago, this was done directly by representing that violence or some of its aftermath: they would represent partisanship and its aggressions or make clear references to the armed conflict. I believe young Colombian writers are doing what can be described as “elaborations” on that violence. These do not necessarily spring from specific acts of political violence. Instead, they are more about what it means to coexist and inhabit a violent reality.

I once tried writing about this direct violence, but it just didn’t come out naturally. Colombia has a very complex history and form of violence, one that I have not experienced directly like some other victims have, so I felt that I was mimicking and appropriating a voice that was not mine. So when I started writing Animals, I was mostly interested in identifying and developing those forms of violence that I inhabit every day and can genuinely speak of. In my case, that was the violence that springs out of class divisions and classism, and gender violence. And I think these happen in tandem with, and are informed by, that bigger, more spectacular political violence of Colombia’s history—drug-dealing and narcoviolence.

Young Colombian writers are doing what can be described as “elaborations” on that violence.

Jaramillo: Class and its inherent violence make their appearance in the relationship Ines establishes with María. It is not evident at first, but when it settles, the friendship between these girls is irrevocably changed and disrupted. What is the point that you wanted to get across?

Esquivel: At the beginning, Ines does not see class. She’s inside the world of her house, and the games she plays with María are somehow equalizing. But we do see that María, who belongs to a lower class, is freer than Ines: she has the outside world, the streets, etc. Ines, being a protected and bourgeois girl, lacks that world and, instead, needs to remain pristine and untouched. Toward the second part, however, as Ines learns how to read, things change. For me, one of the most violent moments in the story is when Ines realizes the class difference between her and María and she executes the power she has for submission and subordination. In that moment, we know that their friendship has ended: they are master and servant. So she goes from the naïveté of childhood to a place where she understands that class dynamics define who she is and how she should act. And, you see, this is not at all distant from that other kind of “spectacular” violence we were just talking about: in the end, those microaggressions are the seed of Colombia’s political struggle.

Jaramillo: Gender violence, on the other hand, doesn’t seem to be something that suddenly enters and disrupts but rather something that is always present, defining every move of the characters.

Esquivel: Well, I think each one of the female characters embodies different ways of being a woman in Colombia. The mother is interesting: she’s a single mom and wants to be young and free, but she’s a mother, so coming to terms with those two things is her biggest conflict. The world tells her that you either live life or you’re a mother. And every time she trespasses this, she’s punished.

And then there is Ines, who has to be well behaved all the time, have good manners, and is always expected to behave in a certain way. And then she rebels against the patriarch that governs over these women, and she is punished too. So I guess the violence I wanted to show is one that exists when the expectations others have about women meet the true and internal desires of these women. What is revealed is an oppressive patriarchy that hurts and minimizes women. A trauma, if you will. And that’s one of the central issues of the book.

Jaramillo: The book starts and ends with apocalyptic scenes. Where did the drive for such an image come from?

Esquivel: I started writing the novel in 2012, when there was some kind of prediction about the end of the world. I started to remember other similar stories and how scared I was of them. And then this horror slowly disappeared and vanished. What I found interesting is that grief is also like this: when someone dies, or a relationship ends, there is an end to the world as you know it. Grief is apocalyptical. But, in the end, it also gives birth to a new world. We are always experiencing the ends and the beginnings of new worlds. The girl in the book is obsessed with the end of the outer world, while in the meantime there are many smaller worlds dying and ending. The world will not end, but her own world, in many ways, ceased to exist. So, in a way, the apocalyptic scenario is a way to talk about her inner world, what died, and what was renewed in her.

Grief is apocalyptical. But, in the end, it also gives birth to a new world.

Jaramillo: I want to talk about the end without giving it away. Let me just say that Ines is looking for her dad. But what she finds is something completely different. One of the most threatening characters appears again. The scene is very Oedipal. As a matter of fact, the end makes me think of Ines’s future relationships with men.

Esquivel: Well, I think there is something very erotic in the entire novel. It does speak of heterosexual relationships from a woman’s perspective. Frankly, it’s utterly perplexing that men and women can have heterosexual relationships and that we have been able to build and sustain a civilization through heterosexuality. Ultimately, men have oppressed women for centuries and are physically menacing. There is always a vote of confidence when a woman establishes a relationship with a man, because there are no guarantees that he won’t kill you. I am not saying that all men are predators; I am speaking from a biological perspective.

Additionally, men have all social institutions in their favor. So, in some ways, it is incredible that women and men build relationships. . . . Anyway, I tried to represent different sides of masculinity, like the father’s tender side, but also the feared and menacing side, like the grandpa’s. So, in a sense, yes, fatherhood and masculinity are somehow blended, and there is a love/hate relationship and fear of their aggression and of their abandonment.

Jaramillo: You’re a feminist. As a matter of fact, you run one of the most important podcasts on feminism in Colombia, Womansplaining. What is this podcast about and how has your experience been as a leading voice in this debate?

Esquivel: It’s fundamentally a podcast about the intersection of feminism and culture at large. It has evolved since it started, trying to answer the questions that the podcast itself has raised. It started by being focused on how certain aspects of our culture are marked by aggression and oppression of women, and really interested in discussing the microaggressions women have to endure. But then it started to change. Feminism has become a lens to analyze “reality” at large. Just to give you an example, questions like, Why aren’t there more women in politics? When you answer this question, you start to delve into bigger structures and social systems. It has given me an opportunity to think out loud and to revise topics that might not be first and foremost a problem of gender, like environmentalism or Colombia’s political violence.

Feminism is not easy to talk about in Colombia or in Latin America at large. There are too many prejudices: there is a lot of misinformation, making it seem like a topic that is only relevant to other feminists. But this podcast has been interesting precisely because while it obviously attracts women who identify with the themes, it is also on the radar of a wider audience.

Jaramillo: What is the role of literature written by women in feminist debates today?

Esquivel: Women have been taking a fundamental role in public debates in Latin America, and one of the most striking examples is the 8M movement (continent-wide protests led by women, focused on massive killings of women, abortion, and inequality at large). But this is a reflection of what is happening: Latin American women writers are writing with a distinctive political agenda that is strong and loud. And it has received notoriety outside Latin America, too. In a way, women writers are contributing in changing that old popular perspective that art is an independent domain from politics and that women are uninterested in it. This is proven by the fact that the more women writers are engaging in a political agenda, the more successful they seem to be.

Latin American women writers are writing with a distinctive political agenda that is strong and loud.

Jaramillo: Have you read yourself in English?

Esquivel: Yes, and I love it. I think it’s even better than in Spanish. Robin Myers, the translator, found gestures of language that I would have been unable to intuit, even in Spanish. I didn’t want the translation to be morphed into a “Latina literature” kind of rhetoric. First, because the novel is not about immigration or anything like that. So I really liked that the translation had no intentions of showing a Latin American experience through an “exotic” lens or through an “immigration experience” lens, as is sometimes the case with Hispanic literature in the United States.

Jaramillo: Do you have any anxiety about how you could be read and interpreted in the United States?

Esquivel: When I have talked about the book in other countries that are not Colombia, people tend to be very interested in the political and historical context—Colombia and its violence in the 1990s. But those are questions that I have never been asked in Colombia: rather, they ask me about childhood, maternity, or the psychological depth of the novel. So I think the cultural and historical context will be of interest in the United States. Hopefully, however, that will also allow me to talk about the other things the novel holds.

April 2020