Historic Black Santa Monica: A Conversation with Leana Brunson-McClain

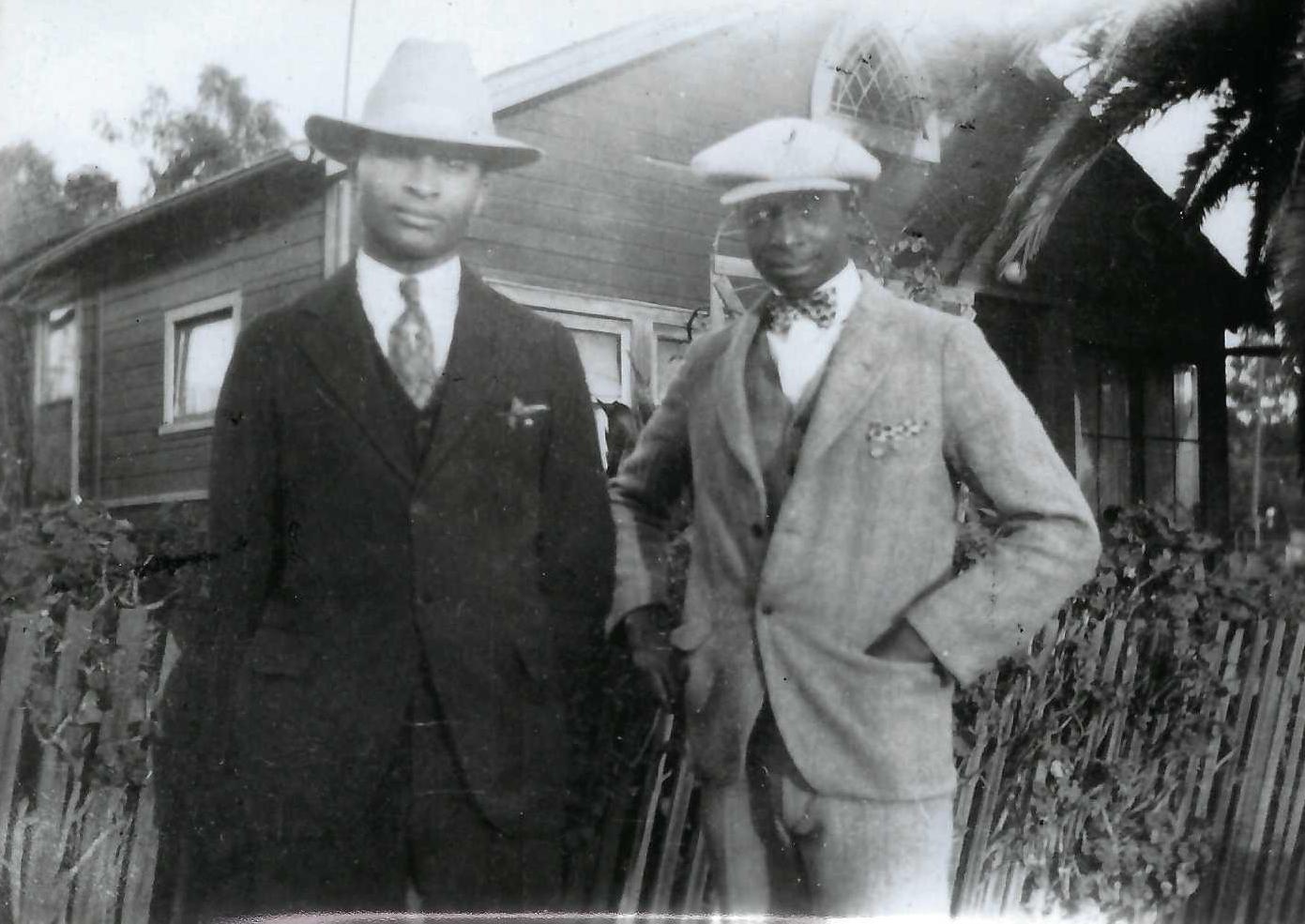

Leana Brunson-McClain grew up in the heart of Santa Monica’s Black community during its heyday in the 1950s and ’60s. According to Brunson lore, the family moved to Santa Monica in 1907, and Leana’s father, Donald Augusta Brunson, was the first Black child to be born there, a distinction that Leana recalls with pride. Donald Brunson is remembered in Santa Monica as a visionary community leader who was able to bridge the city’s Black and white worlds, and who helped to preserve Black institutions during the construction of the Santa Monica Freeway, which displaced the mostly Black and brown neighborhoods in its path. Until recently, the history of Black Santa Monica had largely been forgotten. In my interview with Leana, she reflects on the vibrant community that was and details her efforts to preserve its fading memory.

Karlos K. Hill: Your family has a long history in Santa Monica, so I wonder whether you might be able to talk some about what life was like in the city’s Black community before the area’s residents were scattered by the construction of the Santa Monica Freeway.

Leana Brunson-McClain: My family lived at 1762 Euclid Street, on the corner of Euclid and Michigan—only a block away from where the redlined district started. The house where my father was born was at 5th and Michigan, which was farther west, five blocks from the ocean and almost next door to Santa Monica High School. That’s where we lived until I was five or six years old, and I remember it well. When my grandfather bought the house there in 1905, the location was rural, mainly bean fields. It was a very short street, with no more than maybe eight houses, but it was an integrated street. My father used to call it a Little United Nations, because there were Hispanics and a Chinese family living there along with Black people. In 1952 the high school wanted to expand their ballfield, so they bought the property from the people who owned it, and that’s why we had to move.

My father used to call their street a Little United Nations, because there were Hispanics and a Chinese family living there along with Black people.

My parents wanted to find a house to buy in a similarly integrated part of Santa Monica, but realtors would only sell them houses inside the redlined area, the part of town where African Americans lived. Our church was in that area, and several times when we were on our way home from church, we passed this house on the corner of Euclid and Michigan with a “For Sale by Owner” sign out front. My parents would always say, “Should we stop?” before driving on past. And then one Sunday, they finally did stop. My dad knocked on the door, and a man named Mr. Morales answered it. My dad told him he was interested in buying the house, and Mr. Morales said he would sell it to him. When my dad went to the bank, though, they would not give him a loan because the house was outside the redlined area. When Mr. Morales heard that, he said, “I will carry the note for you until you’re able to find a bank that will give you a loan.” Mr. Morales carried that note for several years. I still have the receipts he’d send back when my father would send him a check. I also have the ledger where my dad recorded the $10 payments he was sending. Eventually, one of the banks in Santa Monica did take the mortgage for the house.

So, we were the first African American family to live in that area. An older woman lived next door to us, and she kept her window shades pulled down on our side for almost a year. She wouldn’t even speak to us. But my parents would always speak to her, and after a while she came around. She ended up being a very close friend of ours and a wonderful neighbor. Santa Monica was still pretty segregated back then when it came to socializing. When my dad went to school, he was usually the only Black kid in the classroom, and because we ended up living where we did, I experienced the same thing. I was the only Black girl in my elementary school, and there were only two Black boys until I was in the fifth grade. We both went to Lincoln Junior High School, and it was a little more integrated. But the redlining meant that certain schools were basically all white, and others were all Black and Hispanic.

The redlining meant that certain schools were basically all white, and others were all Black and Hispanic.

My father was active in a lot of causes in Santa Monica, and he became very well known in both the Black and white communities. So when he passed, it was a very large funeral. One of the speakers was the mayor at the time, the city’s first African American mayor, Nat Trives. My father had started and funded the first African American Boy Scout troop in Santa Monica, and Nat had been a member of it. When the funeral was over, he came back to the house with us, and as we were sitting around the dining room table, he said to my mother, my brother, and me, “Your father has done so much for the community of Santa Monica, there really should be a street named after him. I think we should change the name of Michigan Avenue to Brunson Avenue.” It was a nice thing to hear, but nothing came of it. I ended up moving out of the country and was gone for about seven years, and then my mother passed. When I’d go back to Santa Monica and visit the cemetery where my parents and grandparents are buried, I always went past our old house at Euclid and Michigan, and the street signs at the corner would remind me of what Nat had said.

When my brother passed three years ago, it was kind of a wakeup call for me. I knew that I needed to advocate for the name change, because I was the only one left in the family to do it. So I got in touch with Nat Trives and told him that I wanted to get this done. He was still in contact with people on the city council, so he got the ball rolling. It turned out that the process to change the name of the street would have been too difficult, but they were putting in roundabouts on Michigan at the time, and he was able to get them to name one of those “Brunson Circle.” Even that process took about a year, but the city council voted unanimously in favor of it. So, Brunson Circle is right in front of only the second house that my dad ever lived in. We organized a big celebration to dedicate it, and it was a well-attended event. Not only were we able to honor my father, but I got closure, because the thought that it might not happen had always bothered me.

Hill: Beyond the obvious family connection, why did you feel it was important for Santa Monica to remember your father?

Brunson-McClain: I thought he deserved recognition not only for his civic contributions—he was very involved with the African American community in the city, for instance, including as one of the founders of the AME church there, where his name was on the cornerstone—but also because of the stumbling blocks that were put in his way as one of the only African American people in many situations. He was able to navigate white Santa Monica, if that makes sense; he could walk in both communities and was well respected in both communities. He was in the African American Masons group, but he also received the Humanitarian of the Year Award from the Council of Christians and Jews. He advocated for everyone, and he was a pillar of the community for both Black Santa Monica and white Santa Monica. He was a very religious man, but he was a very gentle and caring man, too. He was also extremely smart and well read.

Hill: There was a successful effort in Los Angeles County to get the city of Manhattan Beach to return land that had been stolen from Black families in the 1920s through the use of eminent domain. I know that eminent domain was used in Santa Monica to acquire the land for the freeway, and that it displaced a lot of Black families. Do you have any thoughts about how what was accomplished in Manhattan Beach might apply to those former residents of the Black community in Santa Monica?

Brunson-McClain: With regard to our first house in Santa Monica, where the property was needed for the high school, Dad always said they were paid a fair price. He didn’t feel like it was taken away from them at all. But the land that was seized from people for the freeway was a different story. The new section of interstate cut right through the heart of the African American community. In fact, the original plan was to take the property where our church stands. My parents and other church members spoke up to request that the route be altered enough to spare the church, and they were successful. If you ever go to the AME Church in Santa Monica, you will see that it sits on a little pie piece of land right next to the freeway. There used to be a city street there, 19th Street, but they chopped it off for the new highway.

A lot of African American and Latino families were displaced, and my mother was on the committee to help them find new housing. Many of the properties that were taken through eminent domain were rental properties, because there weren’t many African Americans who owned land in Santa Monica, but those African American renters were forced to find someplace else to live. Euclid, which is the street we were living on at the time, also got cut in half because of the freeway. We were farther down, so we were not affected, but there were many white families on Euclid that lost their property.

When my parents bought that house on Euclid and Michigan, it cost $13,000. The last time I checked, it had sold for about $3 million. So much changed after that freeway cut through our community. I remember the day it opened. I was a teenager, so that’s where I learned to drive. The freeway made it easy for us to “go to town” on Sunday afternoon to go see the family. But at what cost to everyone who was displaced?

Hill: How is Black Santa Monica today different from the community that you knew?

Brunson-McClain: I rarely get back there anymore, so I can only speak to how it was back in the 1950s and ’60s. It was such a vibrant area, a thriving African American community where everybody knew everybody. Our church, the First African Methodist Episcopal Church, was right in the heart of things. We did not live in that redlined area, and there weren’t really any other African Americans where I went to school, so during the week I was with my white friends, and then on the weekends I was with my church family. I learned to live between the two worlds, but I never forgot who I was: a proud African American child. My parents made sure of that, and they made it a point to teach me African American history.

My mother grew up in the area of Natchez, Mississippi, but my grandfather wanted to get his three girls out of Natchez itself, so he and his brother, who also had several children, moved their families to two nearby African American settlements. My mother’s family lived in the farming community of New Africa, and Uncle Ike and his family lived across the highway in Alligator. We had a family reunion in Natchez maybe ten years ago, and I was able to visit New Africa and see the church where my mom went to school.

I also saw the property that my grandfather was a sharecropper on. He wanted his girls to be educated, so they all went to Alcorn College, and as each one graduated, he would send her out west to Los Angeles, where other family members who had already left were living. That’s how my mother ended up in California. She had never really been around white people at all, but when she married my father and he brought her to Santa Monica, she was thrown into a largely white community. Like my dad, she was able to navigate both worlds. She was very active in the church, but she was also the president of the Santa Monica City College Patrons Association and served on a number of different boards.

I didn’t think much about it at the time, but now I wonder what it was like for a young woman from Natchez, Mississippi, to come to Santa Monica and learn to live in two different worlds like that.

I wonder what it was like for a young woman from Natchez, Mississippi, to come to Santa Monica and learn to live in two different worlds like that.

Hill: As memories of old communities fade away, there’s a sense in which those communities themselves cease to exist. Are there places you can go in the city that bring back memories of Black Santa Monica as you knew it?

Brunson-McClain: Foremost for me would be the First AME Church. I practically grew up in that building, and I know almost every inch of it. My dad was superintendent of the Sunday school, and my mother was the youth director. I played the piano and lit candles for the services. We have an old regulator clock from the church in our family room here, which serves as a nice reminder for me. It had been put in storage when the church was modernized, and it was in pretty poor shape when I first saw it, so my dad and I refinished it together. That clock is a real Santa Monica connection for me, because it hung all those years in the church I grew up in, the church I was baptized in.

In Santa Monica myself, in addition to the church, I feel most connected when I go by the old house on Euclid and when I go to the Woodlawn Cemetery, where my parents and grandparents are buried.

Dad was interviewed more than thirty years ago about his life in Santa Monica. When I read that narrative, I can hear his voice. He loved Santa Monica. It was the only place he ever lived, and he was so proud of his town. Being Black was not going to stop him from doing what he wanted to do. Santa Monica will always be home for me, too. I still feel deeply connected to it.

April 2023