A Griot of the Black German Experience: A Conversation with Katharina Oguntoye

Bearing Witness: In his ongoing column, Karlos K. Hill highlights the efforts of cultural figures doing works of essential good around issues of social justice.

Katharina Oguntoye is a renowned Black German educator, activist, and community leader. A historian, she is best known for authoring the books Showing Our Colors: Afro-German Women Speak Out (1987; Engl. 1992) and Eine afro-deutsche Geschichte (1997; Eng. 2024). She was one of the founders of the JOLIBA Intercultural Network, which provides support for children and families focusing on Afro-German and African families in Berlin, and served as its director for more than two decades.

Oguntoye spent her early childhood in East Germany, two years in Nigeria, and from the age of nine lived in West Germany. Until the Black German movement, which Oguntoye helped found, there were no positive terms for Black Germans, only negative terms like neger, mischling, and “war babies.” In 1984 the African American activist and author Audre Lorde became Oguntoye’s mentor and helped inspire the founding of the Afro-German movement and the use of such terms as “Afro-German” or “Black German” for the first time. Since that time, Oguntoye has worked to promote greater recognition and respect for Black Germans within German society.

In January 2024 Oguntoye was awarded a prestigious Obermayer Award in Berlin for her lifelong commitment to fighting against racism and hate and advocating for intercultural dialogue and reconciliation. Prior to the ceremony, I was able to interview her about her life and about why winning an Obermayer Award is so meaningful to her and to Black German people. Katharina Oguntoye’s story is an inspirational one that deserves to be known more widely.

Karlos Hill: Can you tell me about your childhood and what it was like for you to grow up in Germany?

Katharina Oguntoye: I was born in Zwickau, but from the ages of one to seven, I lived with my family in Leipzig, which is a big town, an old town, in East Germany. We then moved to Nigeria for two years, where we lived in Ife and Ibadan. And then we came back to Germany, but this time to West Germany, to the old town of Heidelberg. It was very nice there; a million tourists visit Heidelberg every year. Before the Wall fell, most people in West Germany had no understanding of how the East worked. Even as a child, I felt very strongly that the atmosphere was different there. The language was the same, but people thought differently and there were different connotations of what people were really about. My experience of being raised partly in the East and partly in the West led me to call myself doppelt Deutsch (double German). I saw things from both sides.

Hill: What was it like to be a young Black woman of Nigerian heritage growing up in Heidelberg? Was there an experience that was defining for you?

Oguntoye: I liked the people around me, and they were nice to me in return. I had a pleasant personality, so people often referred to me as a “nice girl” or a “good girl” because I was so interested in what the grown-ups were saying that I would sit quietly and listen. I was always acknowledged as a person there. That was my experience, but I know it was not that way for everyone, including my father. He was a foreign student finishing his doctorate at the University of Heidelberg, but he was an African man, and my mother said that when he would go to a restaurant, people would look at him like they were happy to see that he could eat with a fork and a knife. (laughter) So then they could acknowledge him as a civilized being. We were targets of racism, of course, but we were lucky enough to be in a situation where we didn’t experience much ostracization.

But even though my experience there was good, I did hear the word neger, which is the German equivalent of the N-word in English. People were always using the N-word. Half the time they would say it to be mean, but at other times it would be used in a so-called neutral way. So it basically meant “Black,” but half the time they would use it to degrade you. One time when I was on the tram with my mother, I said, “Look, there’s an ‘n’ over there.” She calmly said, “You are not to use that word.” I asked, “Why not?” I didn’t know why it was wrong to say it. I was still very small. She said, “I can’t explain it, but it’s not a nice word, and you are not to use it.” I didn’t understand, but I did learn that there are some things you just don’t do. So there was this strange racism all around me, and yet I was treated nicely. As Black Germans, we feel it very immediately if somebody is saying things that are meant to be negative and hurtful. Fortunately for me, it didn’t happen too often in my own life, but on some level I was always aware that it was there.

There was this strange racism all around me, and yet I was treated nicely.

Hill: Not everyone in the United States knows about the Afro-German movement, or even that there are Black Germans. Can you expand a bit for the benefit of those who are not familiar with the work that you and so many others have done to raise awareness?

Oguntoye: When I was growing up, there was no such term as “Afro-German.” I thought of myself as “mixed.” The word for that is mischling, like “mixling”: of mixed heritage. To me, though, the German word mischling does not sound so great. “Mixed” sounds more neutral. Another term we heard frequently was “mulatto,” which basically means the same thing. It’s a Spanish word, but it was used a lot in Germany, and it was associated not only with a mixed heritage but also with exotic and sexualized stereotypes. I think it’s used in English, too. Another term that was around was “half-breed.”

The term Besatzungskinder (children of the occupation) or “war baby” was also common, because there were many German women who had had children with African American soldiers stationed in Germany after World War II. A few years ago, a group of people who are Afro-German with part American heritage published a book entitled Kinder der Befreiung (Children of the liberation), referring to the freeing of Germany, not the occupation of Germany. They had been called “occupation babies” their whole lives, and that was really hurtful—first to have their existence constantly referred to negatively in conjunction with the war and, second, being referred to as babies even though they were adults. It’s like calling a grown man “boy.”

For all these reasons, this is why we suggested the use of “Afro-German.” For the longest time, German identity was connected to a bloodline, meaning that you had to have a great-grandfather who was German to be a German yourself. We wanted to get away from the Nazis’ idea of “bloodline” and the “one-drop rule” in the apartheid sense. We wanted identity to refer to being socialized in a place, to having the focus of your life in a place, whether you had grown up there or whether you moved there later as an adult. If I stay in Germany for twenty or thirty years and I decide to be a German, then I have the right to do so. Africans have as much right to become Germans as everyone else. It has nothing to do with blood.

Africans have as much right to become Germans as everyone else. It has nothing to do with blood.

So that’s how the term “Afro-German” came into wider use, as a way to move beyond terms like “war baby,” “mixling,” “half-breed,” and “mulatto.” Because how can you build a healthy identity around words like those? It’s just not possible. You might decide that you can live with one of them, you might be able to have this personal negotiation with yourself, but it won’t change anything. It doesn’t take away from all the heavy stuff that comes with the words. So that was our reasoning in promoting this new term. At the beginning of the movement, right when the book came out, we had a meeting at which there were thirty or forty young people in the room, and we ended up talking about it again. Some people said that their father was from America, or from the Caribbean, so they were looking more in that direction for their heritage, because “Afro-German” seemed to refer more to Africa. So we came up with another option, “Black German”: Schwarzer Deutscher. In the African American Civil Rights Movement, Black is beautiful in a political sense, right? We had a long and intense discussion, and in the end we voted for using either “Afro-German” or “Black German,” depending on each person’s preference, or even just “German” if that’s what someone preferred.

A person’s identity is not like a passport; it’s an individual choice. So we would each choose our own identity term, but whatever we chose, we would not let anyone call us the N-word. We didn’t think it would be possible to reclaim the word “negro,” so we made the decision to ban it and replace it with our own terminology. That decision was a powerful one.

Hill: Can you give us a brief summary as to how the Afro-German movement got going?

Oguntoye: In 1984 Audre Lorde came to lecture at the Free University in Berlin. A small feminist publishing house offered to publish her work but she said no, the Afro-German women need a book, and so May Ayim and I were asked to be part of writing the first book by and about Afro-Germans. We met two very important eyewitnesses of twentieth-century Afro-German history, the sisters Erika and Doris Diek. They were born in the 1920s and survived the Nazi period. We asked them how this was possible, and suddenly our movement had a history.

The book, Farbe bekennen (Showing Our Colors), includes essays, interviews, poetry, and prose by sixteen Afro-German women. After its publication, May Ayim and I traveled all over Germany giving readings and making the book known. It was Farbe bekennen that inspired Black people in various German towns and cities like Munich and Frankfurt to come together and organize. It was a real catalyst. Then in the mid-1980s I helped found the ISD (Initiative Schwarzer Menschen in Deutschland / Initiative of Black People in Germany) as well as the Black German Women’s group (adefra). Both are still active today. So the book was a means of coming together and discussing and organizing.

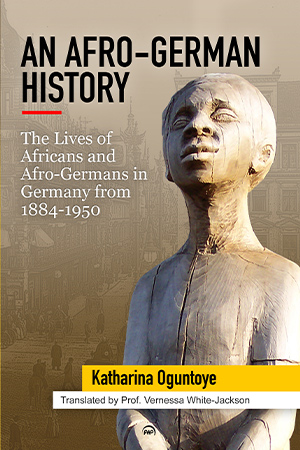

Then in my MA thesis, I looked for a way of proving in the archives what the Diek sisters had told us in oral history interviews. This became my second book, called An Afro-German History, which came out in German in 1997. During my research I documented over one hundred Africans or Afro-Germans in Germany from the nineteenth century onward. And the great news is, the book was finally published this year in the United States by Africa World Press thanks to the wonderful work of Vernessa White-Jackson, professor emeritus from Howard University, who translated it into English.

Hill: In 2020, as I recall, there were protests across Germany in support of George Floyd, and that seems to have been a watershed moment, too. How do you envision the future for Black Germans? Where do you think the Afro-German movement is headed?

Oguntoye: I think the George Floyd incident brought the world to the same level, in the sense of understanding and acknowledging that there is racism. Until then, even though we heard about all the attacks in North America, there were always excuses: the person who was killed must have done something wrong, or there must have been a misunderstanding of some kind. But with George Floyd, the whole world saw it at firsthand; we were all a part of that very public lynching. And with the way the police officer was smiling as he killed him, nobody could make excuses anymore.

With George Floyd, we were all a part of that very public lynching.

We’ve waited all our lives to hear from society that they understand that racism is wrong. And with the Black Lives Matter movement and the George Floyd incident, there was finally an understanding. Now we are in the next stage of movements, and the young people who are involved with Black Lives Matter are also formulating political requests regarding what should be changed and what the standards should be for equality.

This is in part why the Obermayer Award is so meaningful. Growing up in Germany as an Afro-German, I was always very cognizant of the history of the Holocaust and the atrocities committed by the Nazis against Jews, Blacks, Sinti, Roma, gays, and other groups. The Obermayer award-winners are all doing such excellent remembrance work. Now, through their Widen the Circle program, there is a very fruitful exchange happening, and I am very honored to be a part of it. The best thing is, there are a lot of young people involved! I don’t know what the future holds, but I’m happy to see that the next generations are finding their way.

Hill: According to a national survey that was conducted in 2020, there are about one million people in Germany who identify as Black German or Afro-German. That’s a tangible impact which is directly connected to your work and your legacy. Because of the negative ways in which you saw those around you being treated, you started a movement to reframe how Black people in Germany understood themselves and how white people in Germany should refer to them, and now, some forty years later, there are a million people saying, “We are Black German.”

The last time we talked, you told me that white Germans didn’t see Black Germans as Germans; they only saw stereotypes, and they treated you accordingly. You said, “We had to invent a new identity for ourselves because they just didn’t see us.” The more I thought about that statement, the more I was struck by the realization that you’re not just a historian of the Black German experience, you are a griot of the Black German experience. In creating such a positive identity for Afro-Germans, you have given the next generation the strong foundation they will need in writing their own next chapter of this history.

January 2024

Editorial note: Oguntoye’s seminal text An Afro-German History: The Lives of Africans and Afro-Germans in Germany from 1884–1950 (1997), the result of the author’s pledge to research, verify, and give voice to the “lived stories” of Black Germans, was integral to encouraging socially and politically marginalized Germans to embrace and openly declare their full identities. While Germany labored through reunification, An Afro-German History lent support to the growing Black German Movement (Initiative Schwarze Deutsche) and increased interest in Black German and Black European studies. The book was recently republished.

Editorial note: Oguntoye’s seminal text An Afro-German History: The Lives of Africans and Afro-Germans in Germany from 1884–1950 (1997), the result of the author’s pledge to research, verify, and give voice to the “lived stories” of Black Germans, was integral to encouraging socially and politically marginalized Germans to embrace and openly declare their full identities. While Germany labored through reunification, An Afro-German History lent support to the growing Black German Movement (Initiative Schwarze Deutsche) and increased interest in Black German and Black European studies. The book was recently republished.