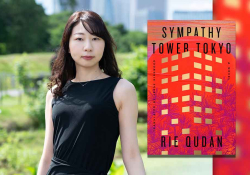

“Our Minds Are Porous and Forgetfulness Seeps In”: A Conversation on Translation and AI with Ilan Stavans

Ilan Stavans has tackled some of the most complex literary problems imaginable, ranging from piecing together the fragmentary work of poetry composed first in Nahuatl to teasing out the cultural bias in Spanish translations of that same work. In addition, he has explored theories of poetics and translation, which he employs in his own literary and critical work. With his skill in pattern recognition, recognizing bias, and evaluating multiple potential interpretations, Stavans is a perfect writer and scholar to chat with about the game-changing advent of AI.

Susan Smith Nash: Your quadruple endeavors—scholar, translator, publisher, teacher—place you at a strategic location in terms of understanding the impact of AI in language and literature. Have you experimented with any of the large-language-model generative AI tools to see how they translate literary texts? If so, what were the initial results?

Ilan Stavans: It has been the equivalent of a child discovering a candy store in the neighborhood. There are all kinds of AI tools: some offer universal blanket approaches, canvasing the digital world without restriction, others narrow the search to specific areas depending on the user’s appetite. I remain uncomfortable with the name AI: if intelligence is “the ability to apply knowledge to manipulate one’s environment or to think abstractly as measured by objective criteria,” as Merriam Webster states, these tools aren’t truly knowledgeable. They simply reconfigure—i.e., repackage—what’s online to please HI, human intelligence. And they are about information, not knowledge, since knowledge is information plus experience. Does AI learn? Does it understand new situations? Does it sort out challenges by means of improvisation?

Still, these tools are magnificent: Natural Learning Processing (NLP), which allows chatbots to understand and translate human languages; Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), where two neural networks compete to generate information; Theory of Mind AI, creating systems to understand human emotions, beliefs, and intentions; and Self-Aware AI, dreaming of possessing consciousness. Some patently more advanced than others, to have them at my disposal makes me think of the appearance of the mechanical printing press—and its deployment of movable type—with Johannes Gutenberg around 1440. Or the invention of the camera by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in the 1820s, the printing telegraph in 1855, the cinematograph 1895, or January 1, 1983, when TCP/IP was officially adopted, enabling different communicating networks to give birth to what we now call the internet. The world was forever transformed with them. The speed with which we experience life is meteoric.

I spent the second week of July 2025 at the Great Books Summer Program discussing AI with about seventy high school kids. One of the topics I posed to them, deliberately thought-provoking, is the similarity between AI and God. I asked them to read chapters 1 and 2 from Genesis in the King James Version. In them, the divine is portrayed as a generative intelligence. It isn’t prompted by humans to act; instead, it is a primordial force activated by its own will. Is the future of AI one in which bots have freedom of their own to create new universes? Astonishingly, we are told that it is through language that God creates the world, approving every act. Verse 3: “And God said, Let there be light, and there was light.” Or verse 5: “And God called the light Day, and the darkness he called Night. And the evening and the morning were the first day.” As in AI, language precedes action and everything is verbalized. Along this line of thought, God is omniscient, almighty, and ubiquitous. As one of the high schoolers posited, the divine is everything everywhere all at once. And one crucial aspect: especially in the Christian Bible, God wants to be loved, which is a development unique to monotheism, a kind of theosophy in reverse. Even the Hebrew Bible, according to theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel, stresses this dimension: the narrative is as much about humans in search of God as it is about God in search of humans. Might AI look for love from humans in the future?

At any rate, the kids understand perfectly the far-reaching implications of the AI technology: labor will be dramatically upended; intellectual laziness is likely to be the default mode; fine literature, more than ever, will need to be about nuance and detail; and the divide between the knows and the know-nots will be emphasized. As part of our discussion, we studied Borges’s story “The Aleph” (1945), in which a fictional Borges comes across a small, iridescent fake sphere in a Buenos Aires basement on Calle Garay, smaller than a golf ball (two or three centimeters in diameter, or roughly an inch), called The Aleph, in which the entire universe might be accessed, but not successively. The Aleph is about infinite space and collapsed time. With the promise of complete, even absolute knowledge, AI too elongates space and compounds time.

There is no such thing as complete, absolute knowledge, though. AI surveys the digital landscape to summarize information. It only accesses the digitized realm; whatever is beyond the digital world—the universe itself—is beyond its scope. It has no bearing on the present, let alone on the future, simply because these dimensions are always outside of the web. In other words, AI only knows what we already know. True, “our minds are porous and forgetfulness seeps in,” argues Borges at the end of “The Aleph.” The most daunting drawback of AI is its incapacity to forget, as in another Borges story, “Funes the Memorious” (1942). After all, forgetting is essential to thinking: in building a map of the world for ourselves, we conjure, we abstract, and we invent. To forget is to select, to prioritize, to individualize knowledge.

Nash: What do you see as any advantages or benefits (if any) of using an AI tool for literary translation? Your next book, Fictional Translations, showcases a series of nonexistent translators.

Stavans: Although Fictional Translations (2026) only partially uses AI, it is a by-product of its age. The volume gathers the work of twelve fictitious translators (Jacinta Candelaria from Colombia, Delphine Ndiaye from Senegal, Albert Ines from Catalunya, Aliaksei Kovalenko from Belarus, et al), delivering renditions of poems I invented in the voice of celebrated poets like Goethe, Cavafy, Valéry, Rilke, Hikmet, Pessoa, and Bolaño.

Nash: Just for clarification, you invented the poems, their translations, and even constructed faux translators? That is amazing! Each one is a deepfake. I’m reminded of Borges.

Stavans: Who lived his life convinced he himself was fake. Or like Pessoa, who created over seventy heteronyms, among them Ricardo Reis, Álvaro de Campos, Bernardo Soares, and Alberto Caeiro. Plus, Pessoa himself, who, in The Book of Disquiet (released posthumously in 1982), wrote: “I wasn’t meant for reality . . .”

After years of reading these poets, I did imitations of the canonized poets. They aren’t replicas because the poems I wrote as if I were Pablo Neruda or Wisława Szymborska aren’t copies; they are altogether new. The book not only features the invented translations but the made-up originals in their respective languages as well: medieval Spanish, eighteenth-century Greek, Turkish, Polish, Ladino, and so on. “The Fearful Hour,” by Russian poet Anna Akhmatova (1889–1966), is an example:

The Fearful Hour

The door creaks like an old woman’s bones,

A shadow falls across the bare stone floor.

I sit in the dark, not knowing how long

The hour will stretch its fingers, cold and sure.

I speak not a word, though my tongue burns still

With the sharpness of truths I dared to say.

They are waiting, their eyes like knives on my will,

While my heart beats too loudly, pounding in dismay.

Oh, this silence! The walls close in,

The weight of my thoughts is a leaden crown.

I thought my voice would break the night, begin

A song of resistance—but now I drown.

They have taken my freedom, my body, my name,

But the soul is not theirs, though they search for it deep.

The world will remember, and history will claim

The broken will rise, though the living may sleep.

Still, the fearful hour creeps without end,

And I count the seconds as they tear away.

The truth I spoke—they will not bend,

But neither will I, in this long, hollow day.

They think I’ll break, they think I will fall,

But the fire in me, it will not cease.

For when they break the body, the spirit stands tall—

The prison is not the soul’s final release.

—Aliaksei Kovalenko (2017)

Albert Ines, one of the translators in Fictional Translations, a Catalan who is a columnist for La Vanguardia in Barcelona, is a lover of AI. Most of the others are skeptical of these tools.

Anyway, AI allows us to translate, in mechanical fashion, works of literature. That these versions lack sophistication is obvious, which doesn’t mean they aren’t useful in a variety of ways. As the publisher of Restless Books, agents, authors, translators, and others from around the globe constantly pitch us work they believe deserves to appear in English. Usually, these pitches are accompanied by a brief translated sample: five to twenty pages, often in a rough English style. At times, I suspect these samples have been generated by AI. If we are intrigued by a book but find the sample too short, we ask AI to translate the rest. Although the rendition will be artless, it will give us a sense of plot, central motifs, character development, and the rest. A caveat: the sample will automatically be another component of the infinite database accessible to AI, setting a record, inadvertently and otherwise, for future translations.

I am acquainted with translators whose first draft is done by AI, to which they apply their style.

Again, among the challenges in a world shaped by AI is discernment: what is human and what is fake? It is conceivable, of course, that the fake supersedes the human, simply because as humans we default to boredom. AI, for better or worse, is alien to the concept of boredom.

Among the challenges in a world shaped by AI is discernment: what is human and what is fake?

Nash: Will AI, as it improves, do the same in the future? How will we be able to tell the difference between deepfake poems, translations, translators, and the real?

Stavans: Impossible—and therein the rub. That, indeed, is one of the side effects of this magisterial revolution: the infinite number of authentic derivatives. The separation between real and bogus, always a fixture of human civilizations, is from now on embedded in our DNA. Consider that you and I are able to tell the difference between a Campbell’s soup can and Andy Warhol’s agitprop depictions of it. AI makes that distinction meaningless: it is able to create real and imagined Campbell’s soup cans, authentic and false Andy Warhol pieces, and an infinite number of derivatives likely more compelling that either of the two.

Nash: Is AI also putting human translators out of work?

Stavans: AI will weed out the uninspired. Just as theater didn’t disappear with the advent of cinema and TV, and just as e-books haven’t eclipsed print books, fine translations are likely to become ever more valuable.

I have an anecdote for you that shows how slow AI processes the vastness of human knowledge. Very shortly after Robert Francis Prevost became Pope Leo XIV, on May 8, 2025, I asked ChatGPT to create a brief biographical profile. It clearly wasn’t ready, so it responded that Pope Leo XIV was a fictional character of Vatican City. It vomited all kinds of unproved ideas about a replacement for Pope Francis. Is this what literature in the age of AI might be?

Nash: What are some of your thoughts about the difficulties of capturing regional, cultural, or historical nuances or multiplicities of meanings in a translation? How do prose and poetry pose unique challenges in each of the cases mentioned earlier? How might these be impacted in the use of AI? You just published a volume with Cambridge University Press called Conversations on Dictionaries: The Universe in a Book.

Stavans: AI is blunt, insipid, unworldly. In Platonic terms, machine-learning algorithms work through pattern recognition, which means the bigger the training set, the better. But it looks at the large picture because it is trained that way, embracing universals. Standardized imperial languages are its preferred mode. Ask for it to explore different varieties of Ladino, the ancestral language of Sephardic Jews, and, metaphorically, it responds with an “uh.” Akkadian? Baghati? Weenhayek? Anuki? AI isn’t of much service.

AI is blunt, insipid, unworldly.

Likewise, dialects, regional parlance, auxiliary languages, and similar linguistic systems. The jargon Mark Twain conflates in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884) is an extraordinary creation, even if it is a shameless appropriation of slave speech on the banks of the Mississippi River. The Spanglish of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao (2007) might be accessible in the digital stratosphere, but it doesn’t continue to evolve in it; only in East LA, San Juan, Spanish Harlem, La Villita in Chicago, and minority urban spaces does it retain the capacity to surprise us. AI doesn’t come up with new language theories; it simply regurgitates those already available.

Conversations on Dictionaries is a collection of twenty-two tête-à-têtes with lexicographers in the same number of languages about how dictionaries have developed historically in their own realm: Ancient Greek, Arabic, Chinese, English, Esperanto, French, German, Hebrew, Irish, Italian, Japanese, Nahuatl, Spanish, Quiché, Yiddish, hybrid languages like Spanglish, Franglais, Portuñol, etc. While each language has developed its own lexicographic tradition, in my mind dictionaries are the most lucid examples of language progress. The very concept of a dictionary is astonishing: to encapsulate, in between covers, all the words in a language. Understandably, there is no such thing as an unabridged dictionary. In spite of their ambition, all dictionaries are finite. They are perishable, not to say forgettable.

The twenty-second conversation, semifictional (or maybe “autofictional”), is a dialogue I once had with a philanthropist who wanted to hire me to produce “the total dictionary,” an online dictionary containing all other dictionaries that have been produced in every language since the beginning of time.

Nash: What are your thoughts about how AI might assist in the idea of a reconstructed text, or might help fill in the gaps where all that is left are remnants or fragments? I’m thinking of Sappho, for example. I’m also thinking of your book Lamentations of Nezahualcóyotl: Nahuatl Poems (2025).

Stavans: Because the past, although slippery, is knowledgeable, AI is a valuable tool to explore its fragmentary nature. I didn’t use AI when writing Lamentations of Nezahualcóyotl, but now I see how useful it could have been in charting the linguistic, historical, religious, military, and cultural scene of the Aztec Empire fifty years before the arrival of Hernán Cortés and the Spanish conquistadors to the city of Tenochtitlán in 1519. As long as the resources are digitized, the possibilities are enormous. Still, it is important to remember that the biases of the past are embedded in AI: yesterday’s prejudices are passed on to tomorrow’s generations.

It is important to remember that the biases of the past are embedded in AI: yesterday’s prejudices are passed on to tomorrow’s generations.

Consider attempting to re-create a medieval manuscript, say La Celestina (1499), by converso lawyer Fernando de Rojas. Parts of the surviving manuscript are purportedly written by an anonymous author. No one knows who that author might have been, although there are all kinds of supposition. Digital technology has allowed us to compare the stylistic patterns of the anonymous author to those of de Rojas, who added a large number of chapters, thus having posterity ascribe the book to him. Could AI go further, analyzing the style of other contemporary authors? Might it show that another chapter or more were lost to history? Scholarship of this kind is possible. It has already allowed us to recognize passages William Shakespeare contributed to plays written by others, a practice, by the way, typical of his time.

Nash: You mentioned the biases of AI. Could it be used to extract that bias or cultural colonialization in some early Spanish translations of Indigenous languages? If yes, how might that work, and how would a scholar such as yourself be vital in such an enterprise?

Stavans: No human endeavor, and therefore no artificial effort that responds to human needs, is ever unbiased. In Lamentations of Nezahualcóyotl, I stress that what we know about the Nahua king, poet, and mystic Nezahualcóyotl (1402–1472) comes through us through endless layers of misinterpretation: the Aztecs who embellished his oeuvre, the Spaniards who reconfigured it, the Mexican nationalists who reframed it, and so on. All of us, without exception, are nothing but a sum of disparate interpretations; that was, is, and forever will be the way of human affairs. Should we be careful to acknowledge our biases? Certainly, although that acknowledgment will not eliminate them altogether because human knowledge is built on contrasting perspectives.

Nash: What are some of the most problematic ethical issues that could arise in using AI for translation, for (a) historical texts that may or may not be complete; (b) Indigenous languages; and (c) politically charged texts?

Stavans: AI is a false mirror, as all mirrors are. Any picture we take of our face—a self-portrait, or else a photo of our face taken by someone else—might be improved or diminished endless times, approximating more or less the original. What it will never be is our face itself, for that exists in the universe, discreet, untrappable, ephemeral. The self-portraits we have of Rembrandt or Van Gogh aren’t Rembrandt or Van Gogh. The same goes for translation: every translation is an estimation. There are almost twenty-four different translations of Don Quixote de la Mancha into English. That is, Shakespeare’s tongue is stunningly rich in Quixotes. Yet Spanish has the one and only original, even if that original itself pretends to be a palimpsest—a translation from the Arabic.

Ours is an age of excesses. The arrival of AI is promised as a panacea on different fronts: medicine, technology, human communication, and so on. While it is likely to reshape our civilization, one thing I assure you it can’t do: make us happy. Happiness, the feeling of contentment, is a result of balance: our qualities and our limitations battle it out at every moment. AI will accelerate the speed of information, it might help endangered languages be recorded before they are eclipsed from human memory, and it will disseminate ideas and texts in a free-flowing market that is likely to destabilize governments, particularly democratic ones. AI is extraordinary in its potential as well as in its dangers. As in the discussion of weapons, its ultimate function will depend on us, because guns don’t kill people, people kill people.

As a teacher, the arrival of AI into the classroom is both stimulating and disconcerting. It is reported that a whopping 90 percent of students already use AI in their education. Among teachers, the percentage must be similar, if not always acknowledged. In Austin, Texas, known as a technology hub, Alpha school, all private, is a new fad. Students have a teacher for only a couple of hours a day; the rest is spent on AI-powered screens. From Texas, this educational model is spreading like wildfire to other cities: Miami, New York. I’m concerned that the distinction between information and knowledge is being obliterated. Information is universal and free-flowing; anyone with basic skills might access it. Knowledge isn’t only experiential but epiphanic; it is how each one of us digests—i.e., individualizes—information.

To put it another way, whereas information is never-ending, knowledge is finite, allows, and even celebrates, error, and cannot be replicated in its totality without it being turned into information again. The classroom is the place we change our minds. Doubt is its true engine. Knowing everything is impossible. We learn our own limitations by interacting with others. Undeniably, it is in the classroom where HI, human intelligence, is able to self-reflect. That self-reflection depends on contact with others. It thrives not only longitudinally, meaning through exchanges with our same-age peers, but generationally, with our elders, which is what teachers are. These days, there is a deep distrust of teachers. Yet teachers have experience. They themselves have been students at some point and, thus, have learned through trial and error. The passing of values from one generation to the next is in question nowadays, and distrusting teachers is a symptom of that doubt. It is a sad comment about our fractured, dislocated times.

AI is a machine. HI is a living organism. I am grateful that AI, in its current form, made its debut in the last quarter of my life. Otherwise freedom, as I understand it, would have been curtailed.

July 2025

Ilan Stavans (b. 1961) is the Lewis-Sebring Professor in Latin American and Latino Culture at Amherst College and publisher of Restless Books. His books include I Love My Selfie (Duke, with Adál), Quixote: The Novel and the World (Norton), and, most recently, Lamentations of Nezahualcóyotl: Nahuatl Poems (Restless) and Conversations on Dictionaries: The Universe in a Book (Cambridge). He has translated into English the poetry of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Rubén Darío, Jorge Luis Borges, and Pablo Neruda, among others. He is also the editor of The FSG Book of Twentieth-Century Latin American Poetry (2011). Stavans is a 2025–26 New York Public Library–Fordham University fellow, finishing a book on Hispanic anti-Semitism.