Moving House

A frequent WLT contributor faces a quandary likely faced by book reviewers, and avid readers, everywhere: which books to take with them when moving house?

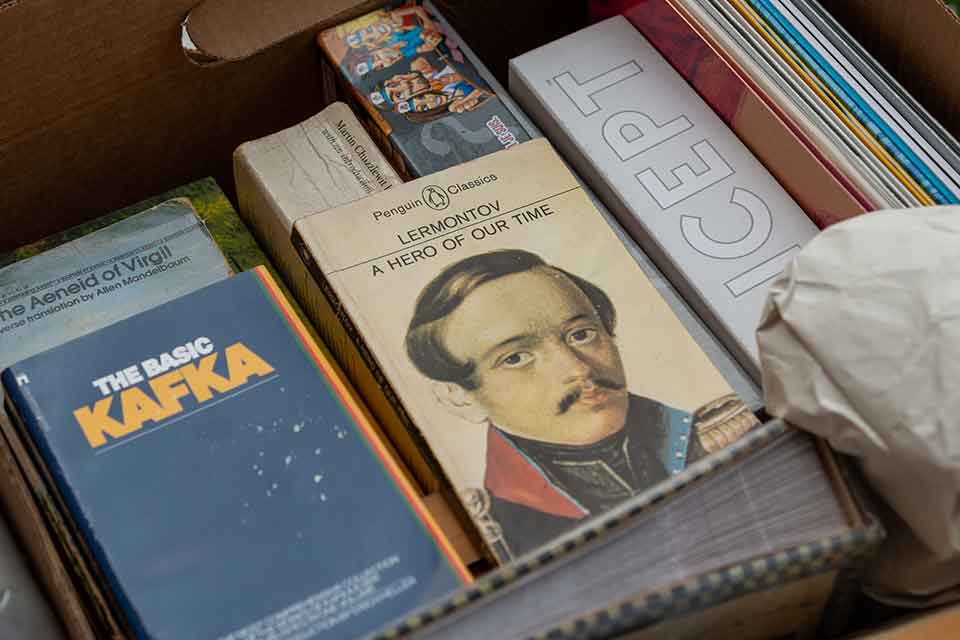

A little while back, I moved house again. Though it wasn’t a great distance—only a few miles—how much easier it would have been were I not burdened with some five hundred books. Yet it is nearly impossible to lessen the number. Moving, in its stock-taking of possessions, presented the opportunity to strip away a good number. But where to start? I’ve carted Middlemarch around unread for six years across four countries, but who’s to say I won’t get around to it soon? And yes, three copies of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is excessive, but each one is unique, taken from a different part of the globe. And the books in Azeri, a language I don’t read—gifts! I couldn’t abuse my friends in Baku and Xaçmaz that way. Taking a break from boxing these up, I went on a short walk, only to return with The Oxford Book of Travel Verse, a doorstop volume that added about ten pounds to my belongings.

When my shelves were half-bare and I had filled the tenth box, I thought: How the hell did Robert Louis Stevenson get his books from Scotland to San Francisco, and from there to Samoa? I paused my packing and opened up his Vailima Letters. “I have no books,” he wrote, sounding mightily depressed, to his friend Sidney Colvin upon his arrival in Vailima, Upolu, in November 1890. Only in May the following year were his books “slowly draining up the road, in a sad state of scatterment and disrepair. . . . Odd leaves and sheets and board—a thing to make a bibliomaniac shed tears—are fished out of odd corners. But I am no bibliomaniac, praise Heaven, and I bear up, and rejoice when I find anything safe.”

I don’t consider myself a bibliomaniac either, but I have come to accept the wide-eyed gawking at my collection, the inevitable question “Have you read all these?”, and the flummoxed looks when I tell them that, no, I can’t even keep up with the new arrivals. Again, we are only talking about five hundred books, but I do not come from a bookish part of the world, and I do not spend much time with bookish people. Where I live, it is not strange to enter a house where books are either hidden from guests or not present at all; I know many people who even take strange pride in their illiteracy, as though they had saved themselves something by turning away from reading.

This matter of moving books from place to place is part of the peripatetic life. It’s a pain, but a manageable one, because the need for the physical manifestation of hope and comfort that books provide is one that roots itself deep. For a time in my early twenties, I lived in my Ford F-150 pickup, sleeping in the backseat with my guitar. This was in Alberta, not a hotbed of literature, but with enough cities and bookstores to push my interest in reading to new levels. I kept my new acquisitions in a wooden crate and spent many cold nights idling the engine and reading Hemingway, Edward Abbey, and motorcycle manuals. The oil fields, where I ended up, were another unashamedly antibook atmosphere, and my little crate became a refuge that gave me both temporary reprieve and the audacity to hope that I, like these authors, might form something greater from my experiences. I thought of my books like a Muslim’s misbahah or a Catholic’s rosary: talismans of illumination.

Under such oppositional backgrounds, it was a comfort to learn that writers are almost always exiles, perhaps from their country or family, but in practically all cases from their surroundings. Whatever their undertaking, no matter how deep their commitment, some significant fragment of themselves always stands apart, observing. And another fragment observes the observance, and so forth. Such splintering is necessary to create worlds. Books work like a caulk, filling the cracks by reminding us that others have been here before, and there can be purpose to such isolation and deprivation. Stevenson knew this, writing in The Ebb-Tide that “Virgil, which he could not exchange against a meal, had often consoled him in his hunger.”

Of course, Stevenson’s problem of nothing to read needn’t exist now, with digital books. But these are a paltry substitute for the real thing. Occasionally, I am asked to review a book, and am duly sent a copy—sometimes physical, sometimes digital, often both. I cannot deny the practicality of the e-book—a thousand in your hand!—however, these digital copies dissipate into nothingness when you aren’t reading them. Without physicality, a coldness lingers over them. The preference of the physical book comes from the same drive to drink wine, stay up late, and plant flowers; these, too, are impractical, indulgent, ephemeral. Yet they constitute the sensual part of life, give the eye something beautiful upon which to rest.

Keeping books isn’t a vital necessity, but doing so creates a sanctuary where new thoughts and ideas can be discovered and rediscovered again and again. My library is a magpie’s jumble, with each book a twig in my spiritual nest. It is not a part of my home so much as it is my home, as integral as the walls, roof, and doors.

Gladstone, Manitoba