Reading in Malaysia: Literature beyond Erasure

Malaysia is among the most multilingual countries in the world, given the peninsula’s key role in the historical oceanic trade. Malaysian schools teach in four major languages: Malay (Bahasa Malaysia), English, Chinese (Mandarin), and Tamil. Many Malaysian writers are multilingual, writing in one or more of these languages, or code-switching in their prose and poetry—languages jostling effortlessly onstage at literary events and open-mics.

Malaysian English writing has made enormous strides since 2002, when Kirpal Singh, Mohammad Quayum, and I co-edited The Merlion and the Hibiscus: Contemporary Short Stories from Singapore and Malaysia, an anthology published by Penguin. I run the Dutt Award for Literary Excellence for Malaysian writers, and it has been a joy to see how reading and writing habits have expanded in the last decade. Readers now have broader interest in YA fiction, speculative fiction, urban noir, diaspora writing, myth-inspired fables, and literature in translation. Some of this interest in fueled by the success of homegrown talents like Hanna Alkaf, Zen Cho, and Tan Twan Eng in the international market, with Tash Aw’s The South—an ode to a vanishing Malaysia—garnering a Booker Prize nomination in 2025.

BookTok Malaysia is revitalizing interest in reading among younger audiences through informal and lively content. Urbanites participate in silent reading events with the KL Reads community at the KL Lake Gardens on weekends. Now there are book clubs, eclectic independent bookstores, and reading events making public spaces available for literature. The rise of social media has boosted exposure for works in all Malaysian languages; while English-language works are more visible to international markets, Malay works have a much broader domestic reach. There is a flourishing market for Malay literature in translation, even as the literatures of non-Malaysian communities often struggle for national visibility, marginalized as they are in terms of government support.

The Printing Presses and Publications Act continues to affect what can be published, imported, or distributed. While censorship is often discussed in relation to themes like sexuality, religion, or politics, what is considered “outside” mainstream norms is often opaque, and self-censorship is pervasive. Between 2020 and mid–2025, dozens of books have been banned, nearly half of them for LGBTQ themes.

Much has changed since 2002, when I first ventured into the Malaysian publishing space. Writers now take more risks for a greater diversity of readers, but existing laws—like the PPPA—informal norms, and religious and moral reservations still shape what can be written, published, and circulated.

Below are essays by the president of PEN Malaysia, an intrepid indie publisher and filmmaker, and one of Malaysia’s leading translators; each essay makes it clear that while we celebrate the flourishing of Malaysian writing and its growing audience, we also need to continue pressing for reform—for clearer and fairer laws, and for protections for authors, publishers, and readers. Only by confronting the uneasy balance between creative freedom and social regulation can Malaysian literature fully claim its place as something daring, honest, and resonant.

– Dipika Mukherjee

Whispers on Pages: Reflections on Reading in Malaysia

by Mahi Ramakrishnan

Words have always been my refuge. This was planted early by my Appa; his voice a steady current flowing through my childhood, rising with the cadence of Tamil poetry. I can still see those humid evenings when he would sit me down, Mahakavi Subramania Bharathi’s verses balanced on his knee.

Acchamillai, acchamillai, accham yenbathillaye.

There is no fear, there is no fear, there is no such thing as fear.

I didn’t know then what those words meant. But they burrowed into me, germinating quietly until they became the marrow of who I am today. They surface when I raise my voice against injustice, when I walk into refugee camps with my camera, when I refuse to bow before authority. Bharathi taught me that fear is a cage we can choose not to enter.

He also gave me fire:

I chanced upon a fiery ember of fire

I hid it in the hollow of a tree!

The forest was laid waste by this small spark of fire . . .

I’ve carried these lines into every space of my work. They remind me that each of us is a spark and that even the smallest flicker of resistance can raze the forest of oppression. Literature is not pastime–it is instruction, fuel, weapon.

And so I look at Malaysia, my home, and wonder: What are we reading now? What sparks are being carried quietly between our palms, hidden in our bags, folded into our commutes?

The answers are as fragmented as the nation itself. In Malay-language markets, shelves groan with self-help, spiritual reflections, and translated thrillers. Romance novels travel from pasar malam or night markets to friend-to-friend exchanges. In English-language shops, BookTok darlings like Colleen Hoover sit beside Sally Rooney and Murakami. Malaysian writers try holding their own—Tash Aw, Tan Twan Eng, Yangsze Choo, Hanna Alkaf—while graphic novels and manga continue their quiet conquest. Tamil-reading homes still return to Bharathi and Kalki Krishnamurthy, especially after the novel Ponniyin Selvan’s cinematic rebirth. That said, young Indians—including those in Tamil schools—have turned away from Bharathi, dismissing the work as boring. Chinese-language readers devour Keigo Higashino and blockbuster crime, romance, or fantasy fiction. This literature is really a mosaic of many tongues, converging only occasionally.

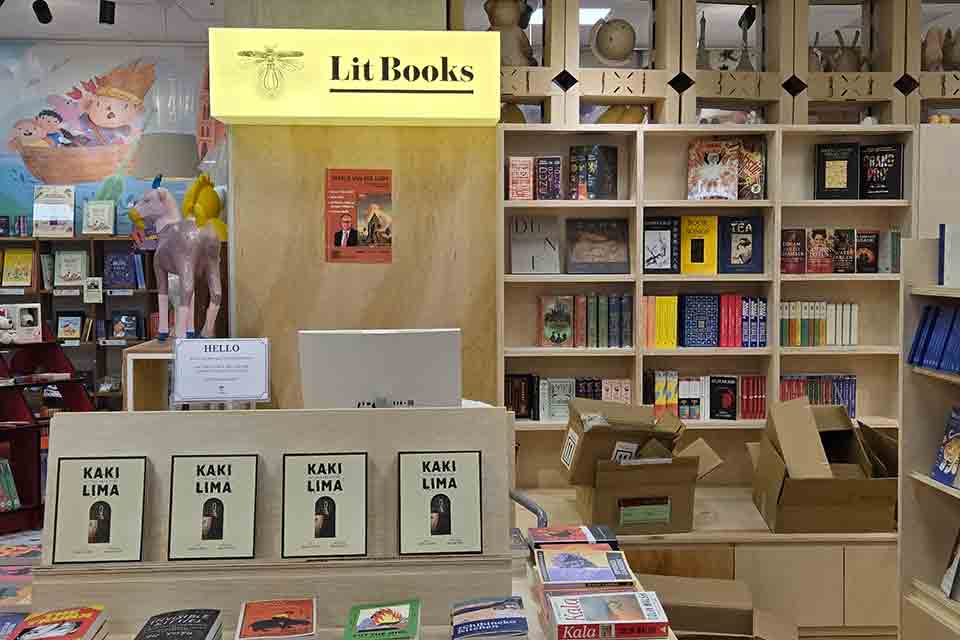

Bookstores here are both fragile and stubborn. MPH and Popular survive on stationery sales. Yet independents such as Lit Books in Bangsar and Gerakbudaya in both Petaling Jaya and Penang curate with tenderness, becoming sanctuaries for dissent and delight. Libraries lag, though digital portals have softened the gaps. Often, community improvises where institutions falter. At Shanar, a neighborhood restaurant in Petaling Jaya, a corner of donated books invites you to borrow for free or drop rm5 to take one home. I’ve lingered there after meals, grateful for the unassuming generosity of such a shelf. Books live best where people gather, eat, and exchange.

Malaysians do read in public somewhat. On trains, between scrolling screens, paperbacks appear. In cafés across Kuala Lumpur and Penang, readers sprawl with lattes and novels, half-posed for Instagram but sometimes lost in their pages. In films, books lean casually against picnic baskets in sunlit parks, a romantic image that never quite plays out in Malaysia. Despite this, reading here, once private, has somehow grown oddly communal.

The most enduring of these gatherings are Sharon Bakar’s “Readings,” where authors read excerpts to a crowd of writers, literature lovers, journalists, academics, and yuppies. It is intimate yet performative, playful yet serious: a reminder that literature breathes loudest when shared.

But over everything, censorship looms like a damp cloth. PEN Malaysia recently met with Home Minister Saifuddin Nasution, who promised to revisit book-banning SOPs. It was theater. Since then, raids have intensified. Booksellers live in quiet dread.

The absurdity reached its peak when Tash Aw’s The South was longlisted for the Booker Prize. Instead of celebration, Home Ministry officers scoured bookshops for the novel. It wasn’t banned, but suspicion lingers, perhaps because of its depiction of love between two men. That the state meets literary recognition with surveillance, not pride, says everything. Books here are still policed for their ability to imagine differently. And yet, book lovers resist by trading PDFs, smuggling titles, reading as if it were rebellion itself.

Social media now shapes tastes as much as shopfronts. BookTok thrives with teary confessions about romances and fantasy sagas. Hashtags like #BookTokMalaysia boost local authors, while Instagram curates literary aesthetics for the algorithm. Offline, book clubs such as Classics Challengers proliferate, sharing everything from feminist collectives to literature that grapples with Malaysian society. In short, stories slip through every crack in the wall.

Among American imports, YA dominates: Angie Thomas, John Green, Suzanne Collins. Michelle Obama’s Becoming and Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime found eager readers. Toni Morrison remains untranslated in Malay; her brilliance still rationed to English-literate circles. Translation is gatekeeping as much as bridge.

In refugee camps I’ve visited, I’ve watched people clutch books, frayed at the edges, in Burmese and English. At the annual Refugee Festival, which I founded nine years back, they’ve recited magical poems, told stories, staged plays. For them, words are not luxury. They are survival.

Sometimes I catch myself stepping outside my body, looking at Mahi the filmmaker, organizer, advocate. She looks tireless, always moving. But inside, I remain the girl listening to her father in the twilight, learning that words can soothe and burn in equal measure. That child still carries embers from poem to protest, from book to screen.

The future of reading in Malaysia feels precarious yet luminous. Precarious because of censorship, digital distraction, economic strain. Luminous because one book can still ignite a revolution of spirit. Malaysians are still reading: in trains, in cafés, at Sharon Bakar’s readings, in whispers about banned titles, in secret PDFs. Reading here is resistance, refuge, and, sometimes, joy.

Malaysians are still reading: in trains, in cafés, at Sharon Bakar’s readings, in whispers about banned titles, in secret PDFs. Reading here is resistance, refuge, and, sometimes, joy.

For me, it always circles back to that moment: Appa’s voice, Bharathi’s verses unfurling like banners in the dark . . . there is no fear.

Perhaps that is the legacy of reading in Malaysia: the quiet courage it plants in us, to resist, to imagine, to burn bright against the silence.

That Cougar Choked My Dick

by Amir Muhammad

I started publishing books in 2007, and, although it’s unseemly to keep such a strict count on these things, I think the total number of notches on my belt so far is about 350. Out of these, four titles have been banned.

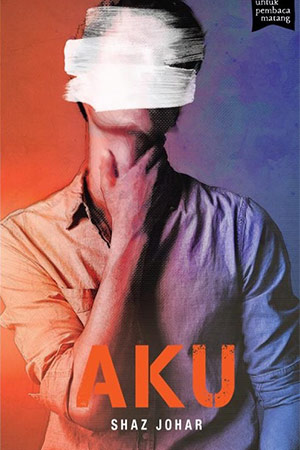

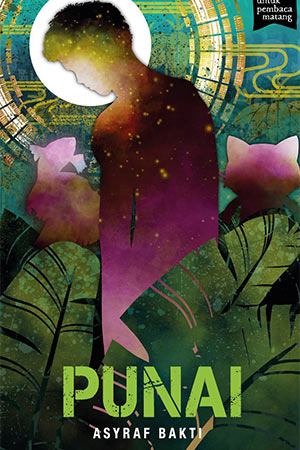

A banned rate of about 1 percent seems decent. I even developed a mnemonic for the titles. The first to get banned was Cekik [Choke] by Ridhwan Saidi; the second was Aku [I] by Shaz Johar; and then in rapid succession came Punai (the word is either a type of bird or slang for penis), by Asyraf Bakti; and Shaz Johar’s Kougar: 2 (which is the sequel to . . . wait for it . . . Kougar, which remains blissfully unbanned). The word is merely a Malay rendering of the American slang term “cougar.” But when “two” is pronounced in English, it sounds like the Malay word “(i)tu,” which is not the same as the Spanish or French tu at all; it just means “that.”

A banned rate of about 1 percent seems decent. I even developed a mnemonic for the titles. The first to get banned was Cekik [Choke] by Ridhwan Saidi; the second was Aku [I] by Shaz Johar; and then in rapid succession came Punai (the word is either a type of bird or slang for penis), by Asyraf Bakti; and Shaz Johar’s Kougar: 2 (which is the sequel to . . . wait for it . . . Kougar, which remains blissfully unbanned). The word is merely a Malay rendering of the American slang term “cougar.” But when “two” is pronounced in English, it sounds like the Malay word “(i)tu,” which is not the same as the Spanish or French tu at all; it just means “that.”

The mnemonic was spontaneously developed when a friend on WhatsApp asked me which books of mine have been banned, and I replied “Kougar tu cekik punai aku” (in English, that is the title of this article).

The first time I got banned, it did make me a little paranoid. Would cops come knocking at my door? Would someone raid my computer to see what files I had? But when nothing like that happened, I just went about my regular boring routine.

Over 3,100 books have been banned in Malaysia since the 1950s. If you want the exact number, do check out the Home Ministry website, where you may search by title, author, or publisher. While the existence of this public list is a type of transparency, as a publisher I have never been told why those books were banned, beyond some vague guff about “moral standards.” In fact, I always found out from journalists initially, rather than from some government official. So, this exact conversation happened four times in the past decade:

Over 3,100 books have been banned in Malaysia since the 1950s. If you want the exact number, do check out the Home Ministry website, where you may search by title, author, or publisher. While the existence of this public list is a type of transparency, as a publisher I have never been told why those books were banned, beyond some vague guff about “moral standards.” In fact, I always found out from journalists initially, rather than from some government official. So, this exact conversation happened four times in the past decade:

Journalist: “Could you give me a comment on that book of yours that just got banned?”

Me: “Err, what book is that?”

I have come to think of bans as an occupational hazard; it’s a price of entry for publishing here. They’re annoying and disruptive but akin to having a piece of half-chewed taugeh stuck between one’s teeth: inconvenient, but hardly the end of the world.

I have come to think of bans as an occupational hazard; it’s a price of entry for publishing here.

This year, I have been thinking a lot about a Facebook post by a Singaporean intellectual. When commenting on some controversy—the details of which are hardly important, as Singapore has the most boring controversies in the world; it’s the price they pay for having the best airport—Cherian George (yes, he’s the Singaporean intellectual I am talking about, in case you think I was referring to that other Singaporean intellectual) said: “Resilient authoritarian rulers resort to obvious, spectacular censorship only occasionally, to remind the public who’s boss; the routine, everyday experience is much more complex and subtle. It’s often in the form of economic incentives and disincentives.”

This is fantastic and relatable to me. I have been the recipient of various grants and government incentives in both of my chosen fields: book publishing and movie producing. (I have had two documentaries banned too, but since this is a literature magazine, I shall stick to books.)

This is fantastic and relatable to me. I have been the recipient of various grants and government incentives in both of my chosen fields: book publishing and movie producing. (I have had two documentaries banned too, but since this is a literature magazine, I shall stick to books.)

Our government gives annual book vouchers to university students, and some of them choose to buy our books, and this boosts our bottom line. Those students just need to choose from all the nonbanned books, which still greatly outnumber our banned ones.

There’s a certain type of middle-class liberal who will smirk, “Banning a book just makes people look for it harder!” Alas, this is not the case in Malaysia, as we tend to be lazy. It’s not worthwhile to even try selling these things underground. After a couple of days in the news, people will go back to gossiping about politics or royalty or whatever.

As Patrick Hamilton, or someone who lived in the same time as him, once said: “A fate worse than getting banned, for a book, is remaining unread.” And, as someone who has hundreds of unread titles on my shelves, I am guilty of perpetuating this worse-than-banned fate for many books, most of which I bought because they were by people I know and I just wanted to be polite. This phenomenon of having many unread books is something the Japanese call tsundere (or a word very much like it).

Will these bans affect the books I’ll publish in the future? At this point, no. (But in the future, who knows? That is why I have been thinking of that Cherian George post.) I hope to continue publishing the authors I deem interesting. Most of our books are in the Malay language, which doesn’t have a great deal of variety when it comes to content. Most Malay fiction tends to be romance, and most Malay nonfiction tends to be “how to get rich or go to heaven or preferably both.” Although this has gotten better in the past two decades, thanks to some colleagues of mine in the book trade (most of whom choose to remain silent whenever someone else’s book is banned, bless them), why not strive for more?

Along the way, yes, we will sometimes get banned and sometimes lose money (guess which option is scarier), but what’s the alternative? Getting a real job? Now that’s a prospect that will get me choking on my batang buruk.

The Afterlife of Books: Secondhand Circles in Malaysia

by Pauline Fan

Books rarely die in Malaysia. They live on in afterlives both physical and virtual, crossing thresholds of time and technology. Passed from hand to hand, wrapped in newspaper, annotated in blue ink, hidden in drawers that smell of camphor and dust. They are rescued from forgotten storerooms, revived in Facebook posts, reborn in parcels that travel across land and water. They bear the faint scent of mildew and rain, their pages alive with the ghostly traces of readers who once folded and underlined them.

Books rarely die in Malaysia. They live on in afterlives both physical and virtual, crossing thresholds of time and technology.

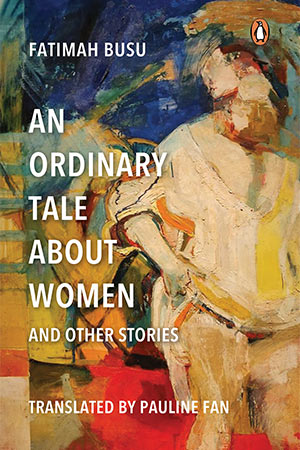

My own journey into this afterlife was as a literary translator searching for the lost short stories of Fatimah Busu, one of Malaysia’s most fearless and inventive writers. Her stories—often centered on the lives of Malay women—are fierce, satirical, and unsparing in their critiques of hypocrisy and patriarchy. But by the time I began my search, most of her collections had long gone out of print.

My own journey into this afterlife was as a literary translator searching for the lost short stories of Fatimah Busu, one of Malaysia’s most fearless and inventive writers. Her stories—often centered on the lives of Malay women—are fierce, satirical, and unsparing in their critiques of hypocrisy and patriarchy. But by the time I began my search, most of her collections had long gone out of print.

I turned to the improvised, vibrant world of secondhand Malay books, which now thrives online. Facebook has become the nerve center of this underground literary economy. Groups such as Kolektor Buku-Buku SeMalaysia, Kelab Pengumpul Buku dan Majalah Antik, Tuju Buku, and Buku terpakai trade out-of-print titles with reverence and excitement. Each post follows a familiar rhythm: first, a photograph of a yellowed paperback, perhaps Fatimah Busu’s Salam Maria, a volume of essays by Za’ba, or a well-thumbed collection by Keris Mas. Within minutes, the comments appear: Berminat (“interested”), Nak (“I want this”), followed by the seller’s reply, Ditempah (“booked”). It’s a language of affection and urgency, shorthand for longing.

Sometimes rare titles are auctioned live, the comment thread turning into a feverish literary marketplace. Occasionally, sellers tell stories about where a book was excavated: an old teacher’s library, a deceased father’s collection, a pile discovered in a kampung storeroom. Each book’s survival feels like an act of quiet rebellion against forgetting.

My search for Fatimah Busu’s works stretched over months. I scoured these online bazaars, exchanging messages late into the night with strangers who had become fellow archivists. Some sent me scanned pages before parting with the originals; others slipped handwritten notes of appreciation into their parcels. One secondhand bookseller in Johor, Omar Bachok, became a close ally in my search and tracked down old anthologies published by Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka in the 1970s, featuring Fatimah Busu’s early award-winning stories. Piece by piece, I gathered the material that would form my translation, An Ordinary Tale about Women and Other Stories (2024).

What began as research became something more intimate: an act of recovery, a kind of listening. Each rescued book carried not only Fatimah’s voice but also the echoes of an era when Malay literature burned with idealism and defiance. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka (DBP), the national institute for language and literature, had just been born. Its origins trace back to Balai Pustaka in Johor, founded in 1956 as a modest department under the Ministry of Education. During the Third Malay Literary and Language Congress later that year, it was renamed DBP, with headquarters set up in Kuala Lumpur in 1957, the year of Malaya’s independence.

In those early years, DBP was a revolutionary force. It became the crucible where Malay writers, freed from colonial hierarchies, imagined a new literary and linguistic destiny. The establishment of Malay as our national language was not merely administrative; it was political, emotional, and philosophical. Language became the vessel for the idea of nationhood, a means of liberation from colonial powers, and a framework for imagining a shared identity.

Writers like Usman Awang, A. Samad Said, and Shahnon Ahmad were animated by the urgency of imagining a new nation through language. Their words carried the conviction that literature could shape the soul of a people. Even now, their sentences pulse with that visionary energy, something readers continue to seek in an age of scrolling and fragmentation.

Over time, that fire dimmed. The institution that once ignited a linguistic awakening settled into bureaucracy, preserving rather than provoking. The hunger for renewal—that wild, original freedom of the Malay voice—has drifted to the margins. It lives on in readers, translators, and secondhand traders who refuse to let the language ossify.

For me, this yearning took another, more personal form: the search for a particular edition of Shahnon Ahmad’s Srengenge (1973). It was the first Malay novel I ever read, and it stunned me with the terrible beauty of its opening line: “Srengenge tersergam hodoh macam setan” (Srengenge loomed, hideous as a demon).

In that single sentence, I learned how landscape, superstition, and inner torment could coexist, at once visceral and luminous. I remember the cover as if it were still before me: blue-green, with a sun (or perhaps a moon) rising over a jagged mountain, like the unblinking eye of a cyclops.

I searched for that exact edition for weeks. Copies surfaced online, but none matched the one in my memory. On Carousell, I messaged sellers who replied with photographs of cracked spines and dog-eared pages, their captions brief, their offers fleeting. The right edition never appeared. Yet the search itself became its own kind of reading, a meditation on how literature survives through memory and desire.

Each exchange reminded me that books in Malaysia survive, not through institutions, but through individuals. In this archipelago of afterlives, secondhand booksellers form an unseen network of memory keepers—a living web of exchanges, part marketplace, part archive. It is through them that we continue to read together, across time.

I often wonder what happens to a book after its first life ends, when it disappears from syllabuses and shelves. Its survival depends on those who refuse to let it vanish. To read and translate in Malaysia is to dwell among ghosts, to listen for voices that might otherwise be lost.