Where Are You? Rematriation and the Interconnections between Language, Body, and Land

Rematriation, a concept advanced by Lee Maracle (1950–2021), among other Indigenous women, is “the process of restoring lands and cultures, done with deep reverence to honor not only the past and present but also the future, and rooted in Indigenous law” (IndigiNews). Here, the authors relate their own rematriation work in Oklahoma, Iraq, and beyond.

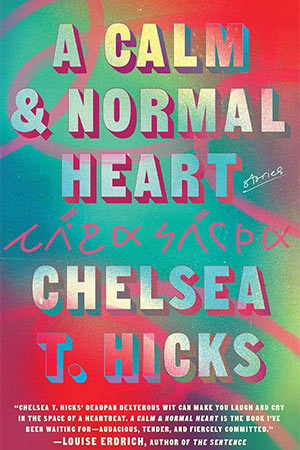

Chelsea: Land provides us with food, nourishment, and life, and this is true whether or not we are comfortable acknowledging land as a relative. Many of us have been taught not to acknowledge land as a relative. In my book A Calm & Normal Heart, there is a story in which an Indigenous character asks a white character where he is from.

“So,” she says as Daren comes back in and leans against the counter. “Where are you from originally?”

Daren replies that his family is from Southern California, and he grew up in San Francisco.

The Indigenous character, who is named Mary, intervenes in his identification with Indigenous lands.

“Oh,” she says. “So, would that be, like, England?”

He looks kind of freaked out. “Oh, hm. I don’t really know much about that stuff.”

When I was returning for the first time to my ancestral lands in Missouri, I felt like my spirit was just a little bit outside of my body, by several inches or feet in every direction. I was with a relative and the groundskeeper, and it was nighttime. While walking downhill on a slightly inclined slope of grass, it was like hundreds of hands came, and they pushed my spirit back into my body so that it was contained again inside of the boundaries of my skin.

I have had a lot of healing experiences like that in relation to land. And water, I have learned a lot about what we can do when we talk with water. Just to acknowledge water is a start, how even when we communicate with our cell phones, water cools the servers that store the data.

Alana: When I landed in Iraq in 2011, to teach at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani (AUIS), I had questions. Questions follow questions. “Behind the mountain, there is another mountain”; isn’t that how one koan goes?

I did not know I was writing Dream State, published with Unnamed this year, as I spent a decade and a half speaking with, learning from, and conducting more formal interviews with the culture makers and keepers of Iraq. I knew that I was not only a poet but a teacher. I knew that Iraq had had enough of Americans taking what helped them and leaving. I didn’t want to only write or even only translate. I wanted to write with, translate with, learn with.

In one interview, which found its way into Dream State, the deeply dedicated Kurdish translator and intellectual Halo Fariq said, “Before I began to translate I was just like any other reader, sitting at home and reading, but then, when my English was good enough, I thought, Halo, don’t be selfish. It’s selfish to sit at home and do what you love. So, I started translating.” His impulse to be at home in motion felt familiar to me.

I am foreign. That is a gift that gives and cuts. All gifts do. This is mine: to be foreign and to learn. I live in a country where fifteen years in, I can suddenly feel naïve. Is it such a bad thing to be cut? Then you are open. Unless you live open, then we don’t call it bleeding, but hemorrhaging.

I may live in stories, but I am still a body. So, where am I? Where is my land? Who do I write for? Why do I think those questions are intimately connected?

Chelsea: I have had to make a home of my body at times when I felt I had no home. I’m not sure we used to have that feeling as frequently before contact and land removals all over the world.

I have had to make a home of my body at times when I felt I had no home.—Chelsea

To promote health and land protection, Indigenous people have been inviting non-Indigenous back to land protection and land empowerment. We’ve been doing this for hundreds of years. Tadodaho Leon Shenandoah said, “Creator sent everyone here for a reason. I don’t know what the reason is, but it’s up to all of us to figure that out.” I think this is something we can ask the land.

To promote health and land protection, Indigenous people have been inviting non-Indigenous back to land protection and land empowerment. We’ve been doing this for hundreds of years. Tadodaho Leon Shenandoah said, “Creator sent everyone here for a reason. I don’t know what the reason is, but it’s up to all of us to figure that out.” I think this is something we can ask the land.

Alana: Zêdan Xelef, a poet, translator, and keeper of archives, introduced me to the oral literature of Shingal, the ancestral homelands of the Êzîdî people. By their own count, Êzîdîs have survived seventy-two genocides, the latest of which began in 2014, at the hands of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. Between the 2014 genocide and the 2020 onset of Covid-19, which disproportionately affected older generations, the entire Êzîdî archive was, once again, at risk. Together with Professor Christine Robins from the University of Exeter and Emad Bashar, another astonishing poet and keeper of archives from Shingal, we brought together young Êzîdî oral historians, musicians, singers, and storytellers to document, celebrate, and bring audiences back to their own endangered literature.

“Endangered literature” here isn’t buildings and books burning, it’s people. How does one measure the success of a genocide? The number of people killed vs. the total population, sure, but memory is kept among people. We gather around the storyteller, who remembers, and then tells the story. The storyteller and the audience member each do their own work to tend the archive. So, displacement and disruption of community is just as lethal as other, more conventionally recognized forms of human violence.

Over the years, Zêdan and I have built our own little lexicon. We call each other “listening creatures.” If we are listening creatures, is it possible we have found our people? Listening people? If we are a people, what is our land? Language? Or the space two people make between themselves? I first glimpsed the concept through the writings of Primo Levi.

Chelsea: Some of the natural leaders among people in Europe when they retained remnants of their Indigeneity were women. They were older, nurturing, planting, story-holding women who ran common areas, gardens where people could grow food and eat. These women were creating a problem for the lords, because they were no longer as wealthy with fewer men working on their land.

Because people were able to live without reliance on their feudal lords and the feudal lords lost “tenants,” the powerful and wealthy began a smear campaign against these women, manipulating the people so that no one would want to be associated with them any longer. The men said that those older women who were natural leaders, and who bent to talk to the land, that they were hags. Those men used the maligning magic of the word witch and were able to get rid of the people’s natural leaders.

What they did was they burned their natural leaders. The Occitan people and Cherie Dimaline told me these things. That burning of our natural leaders is a loss of Indigeneity. Those women were natural, land-based leaders because they took care of people and nurtured, offering repair. The thing to heal that division now will be the returning of stolen land and the restoration of our relationship to our mother. You are a mother, too, who is offering repair, and you have been targeted for that.

So, where are you? Still, few want to be associated with the hag and the witch, and this makes a taboo out of a community-caring mother who does not only center her nuclear family.

Alana: When the smear campaign comes for you, it’s the witches who stand with you. The natural leaders you describe, Chelsea, within the feudal era were a threat to the feudal system because they kept people at home within their own lands. In Iraq, today, those who haven’t gone into the diaspora community contend with life in exile at home.

On March 19, 2003, when American forces launched Operation Iraqi Freedom, the “shock and awe” airstrikes targeted the Ministry of Defense. Across the street was the Iraqi National Library and Archive (INLA). Within the month, the INLA’s collection was mostly ash. Ban Jalal, who joined the INLA in 1994 and worked her way up over nearly two decades to serving now as director of the National Library, is one of Iraq’s natural leaders, to use your term. When I sat with her, she told me, “1920–2003 burned. We lost eighty-three years.” That is exile within your own home.

On April 19, 2003, Ban traversed the city to get back to work. Her neighbor drove her. Swerving around bodies, doubling back at craters, taking detours to avoid roadblocks or raging fires, her neighbor kept telling her, “You just keep your eyes inside the car, my sister.” He drove her to work like this for months. He looked for her. He asked himself to examine the mangled roads, intersections, and buildings, so he could recognize the home that now existed only within his imagination. He navigated the real and imagined Baghdad for her. So she could get to work on books, what Dimaline called in her NSK acceptance speech “homes for stories.” This is exile and arrival. He made exile its own occasion for arrival.

For nearly a decade, Ban had started her day at the INLA by picking a few roses from the gardens for her desk as she walked in. When she arrived on April 19, the gardens were gone. Diesel tanks and rubble littered the pockmarked earth. The doors to the great reading hall had been blown off. From the entrance, she could see piles of ash, scorched remnants of books, manuscripts, periodicals. She didn’t know where to start. She compared it to moving into a new house. She began to clean, sweeping up the ash, but when she went to empty her dustpan into the trash, she froze. How could she throw away these books? These books that no one could recognize or read ever again? In places, she told me, the INLA was shin-deep in ash. No one could help the books that remained without cleaning, but how could she empty the dustpan?

Displacement isn’t something that happens once and then politely stops so you can recover and consciously create a new and safe sense of home; it’s an ongoing reality within language, land, and the body. I am speaking about Iraq, but all I need to do here is glance at the Indigenous experience in America. Is my language safe? Is my land safe? Is my body safe? The resounding answer for most people I know and love is “No.” That “No” is not an end. It can’t be.

Ban sat with me, an American, and told me these stories inside the same building she’d brought herself to clean. Listen long enough, and the individual builds into quite the arc.

Chelsea: You are learning original teachings but not commercializing them. That is an Indigenous way of story.

Alana: I do not need to be in Baghdad or Mosul or Shingal or Slemani. I choose to put my body there, for the sake of listening. That changes every space I enter. That changes every conversation I have. That changes me. You and I ask each other, “Where are you?” We are asking the reader right now, too. Where are you?

Chelsea: When people were coming on the boats here, there was a story about this time from Stó:lō storyteller Lee Maracle. She passed this down to Cherie Dimaline, who shared it with a cohort of my classmates at the University of Oklahoma in Dr. Laura Harjo’s seminar on Dimaline’s work. I am going to tell you that story, because she told us we can use all of what she gave us, and she is a generous person like that.

The people who were coming on boats had killed their natural leaders, which meant they didn’t have teachings and they didn’t have mothers. This is a way of saying they didn’t have the teachings of their old women, whom they had burned, because they had been manipulated by the high-status resource-hoarding people, those lords. People who don’t have teachings can be very violent because they’re trying to survive. It can be easy to be manipulated, too, and not know it.

I don’t think the languages are safe, because the English we have is part of the worldview that allowed them to kill their mothers, their land, their natural leaders. No, the languages are not safe. They never will be until the culture that is now dominating mourns their murdered mothers and their land disconnection.

Listening makes a land within the land.—Alana

Alana: Listening makes a land within the land. Listening reminds me of what some call passive labor, which isn’t at all passive. The body opens and the opening feels endless. It is wild change, outside your control, and you must accept it or the birth arrests.

The constructs we build around opening with others—the interview, the conversation, the classroom, even the novel, the poem, even rhyme, meter, even narrative itself—help belay the terror of that endlessness opening, so that we can reach for experience, maybe even understanding.

Parenthood, so far, for me, is constant rematriation. Personhood is constant rematriation. Sometimes that has fierce energy to it. Sometimes, exhaustion. Cherie Dimaline, in The Marrow Thieves, isn’t asking some toothless question when she writes, “. . . just what we would do for the ebb and pull of the dream . . .”

Chelsea: Right. How willing are we to weep for hours and hours? I know grieving brings dreams back. I work with my Osage language and have been learning it since 2017, and I have been doing this work with my community since 2019. This work has required so much grieving from me; I have gotten so much energy and inspiration and joy back in return. I was once afraid to feel like that, and I had a habit of despair. Now I am strong because of my land, language, community. One of the happiest times for me is sitting down to work on a poem in Osage with one of my elders, Stephanie Rapp, or helping teach and learn with Osage children at our immersion school, with my wonderful Osage teacher Cameron Pratt.

This work has required so much grieving from me; I have gotten so much energy and inspiration and joy back in return.—Chelsea

Alana: Dimaline describes The Marrow Thieves as science fiction, though as Beyoncé quoted Linda Martell, “Genres are a funny little concept, aren’t they,” perhaps because we need the play of imagining how we can survive what is happening and about to happen. The poets I know who have rematriated, which seems both a decision of a single instant and infinite instances, manage it because they play. Otherwise, the perceived deficit of mastery in the language one craves is too devastating to even glance at. Shame will get you every time. But play moves us into the future again.

Chelsea: Yes! Let’s play into the futures. I like to dance into them, and talk to and listen to land, and dream, and listen to dreams, and listen to our peoples. N. Scott Momaday said we have to more fully imagine who and what we are. When we start to remember, we can imagine and reimagine more.

One way to start that imagining is simply by remembering our ancestral lands, calling them “Mother.”

Pawhuska, Oklahoma / Lisbon, Portugal