Auntie Instructions for the Future: Kinship, Care, and Cherie Dimaline

In addition to chairing the Native American Studies Department at OU and teaching the fall 2025 Neustadt seminar, Laura Harjo took part in a roundtable conversation that discussed Indigenous contexts for understanding Dimaline’s work during the Neustadt Lit Fest.

“You have to stand for your words,” she would tell me. And when that wasn’t enough, she made an association that ensured I would have to be confident, invoking the one thing that could make me act without thought of myself or my anxiety. “I can hear your grandmother in your work. So you stand for your grandmother,” she said. And I did.

—Cherie Dimaline, recalling Lee Maracle in An Anthology of Monsters

Walking into Meacham Auditorium for the Neustadt Lit Fest opening ceremony, I felt anxious and unsure how the festival would unfold. I scanned the crowd for Cherie Dimaline and my students, then hunkered down, sorting through my welcome with notebook in hand. It felt like the stakes were so high, I wanted to welcome her correctly. She has generously shared her stories and imagination with the world. A welcome is not just a formality—it is an act of care and reciprocity.

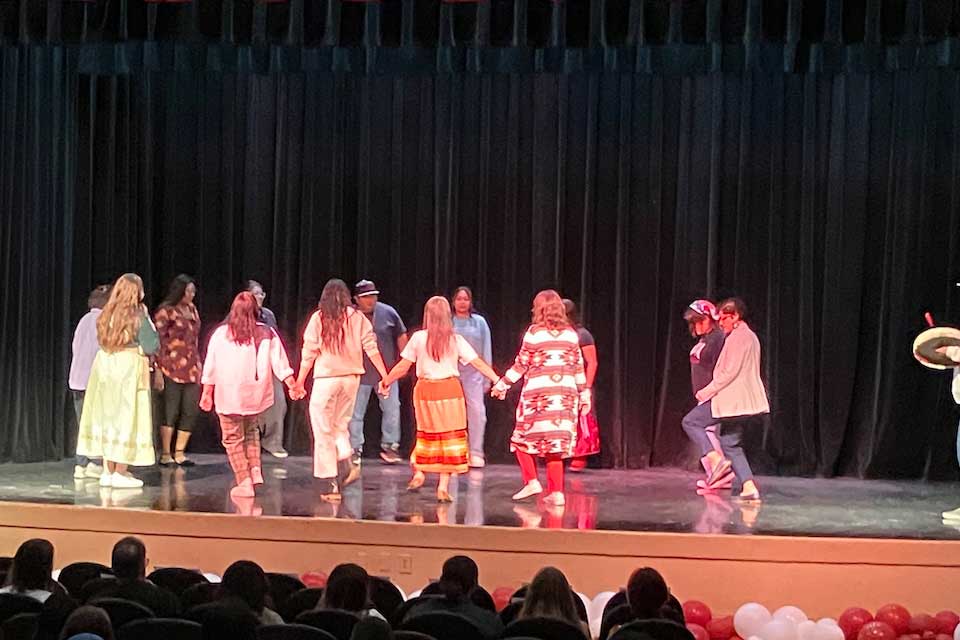

I was comforted by seeing our students standing outside. Our students from the American Indian Student Association would be there taking the lead with a community round dance to welcome and honor Dimaline. The whole opening ceremony passed by like a flash. I guess because we got to dance, smile, and be in community.

During the welcome I shared with her that we read six of her novels, compliments of the Neustadt family and World Literature Today. This journey with her storywork has been instructive and affirming. Earlier this year, I presented my mom, Ellen, with several of Dimaline’s novels. A voracious reader, she was my first teacher, taking us to the library throughout our youth, sneaking books to me when the library still remembered my overdue fines twenty years later for Teen magazine. It was a bonding moment to discuss the books and hear what she, as a Mvskoke elder, thought about them. Pivoting to the students, it has truly been a joy to see them step into Dimaline’s luminous stories and grow with them. Seeing them empowered and encouraged is what our communities need. Cherie Dimaline is the storyteller we need right now. We sighed in relief when she landed at the University of Oklahoma.

Leading up to this event, I have taught many courses over the years, but something was different and special about this course. In part, easing away from intense assignments because I want my students to treat this more as a book club or reading group. Lowering the stakes helps us really get at the things that speak to us from books. I want to hear about the parts of the book that open your heart up, shift your way of thinking, or reflect stories and actors from your own community.

The students read six of her novels, one per week, and arrived to class discussing the aspects of her books that called them in and held their attention. We read the books in the following sequence: The Marrow Thieves, Hunting by Stars, Empire of Wild, VenCo, Anthology of Monsters, and Red Rooms, which was the perfect order for reading the books. As I have come to know all these students through the class, we have puzzled through their questions and interpretations of Dimaline’s work. I have come to a better understanding of who they are and what shapes them and how they carry that with them to the readings and interpretations. One reading that seemed to resonate with the students was the book Anthology of Monsters. Several of the students who were often gripped with anxiety shared their stories about how her work was balm for their souls. The class discussions and zines that they made for Dimaline were more than reading and fulfilling assignments; they were choreographies for another way of being in the world. Teaching her novels felt like collective dreaming.

Several of the students who were often gripped with anxiety shared their stories about how Cherie’s work was balm for their souls.

The Marrow Thieves draws you in from the beginning and catches your emotions. The pace of the book has you feeling fear, caution, hiding, and moments of light and joy—you witness the intense scenes they must endure and the collective love of the made kin that carries them through and sustains them. You feel a beloved attachment to our relatives in The Marrow Thieves, from our baby girl of the group RiRi and our elder Minerva. We have our own versions of beloved kin in The Marrow Thieves. We recognize Minerva and her way of carrying language forward and teaching her kin knowledge of the old ways. We have thirty-nine tribes in Oklahoma with languages carrying instructions. Vnokeckv is Muscogee for love, gadugi is Cherokee for helping one another, and puha is Comanche for medicine.

Our students connected with Cherie on a personal basis, making kinship bonds and pulling one another into community. Her generous and familiar ways felt like we had always known her. She carries pieces of our sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles, moms, dads, and grandparents with which we can recognize and connect. Indigenous futures and dreaming are huge lifts in our community that we ponder and fret about every day. The worry turns into full-blown anxiety. Despite anxiety, the students in the Neustadt seminar are already producing the futures they want to live in.

Dimaline’s work, as influenced by Lee Maracle, in an auntie way shows us another way to be when we are having rough moments in our work or our journey. Moments that prompt us to stand up and speak might produce worry, however, when reflecting on Maracle’s question to Dimaline in Anthology of Monsters, “What do you stand for?” The rehearsal of “knowing what we stand for” is a way of empowering ourselves and our work to create the unactivated possibilities our ancestors wanted for us. This is our north star that instructs us how to shun fear to create the futures we need right now. Dimaline’s speculative fiction on the not-so-distant future reminds us we have already endured versions of these worlds through boarding schools and being hunted today: in stores by security and by law enforcement for our tribal automobile tags.

The rehearsal of “knowing what we stand for” is a way of empowering ourselves and our work to create the unactivated possibilities our ancestors wanted for us.

Dimaline’s work is showing us a map to the next world. The worlds that our ancestors and other Indigenous peoples have already lived through are presented in a dystopic future and the wayfinding tools of relationality, community, ancestral ways of being in the world, and story. She has packed in The Marrow Thieves how we can be in the world together. The richest thing we have in the world is our kin and our relationships. She reminds us of what we forget sometimes. When the materiality of the world falls away, we always have our relationships with one another to sustain and keep us now and into the future.

Upon arriving at Dimaline’s book signing at the ballroom in the union, I saw her holding court in one of our most lavish spaces on campus. It is almost paradoxical to see grape dumplings gently simmering and staged in a fancy vessel. I glanced over the room sorting out the relationality. I felt relieved and at peace to see our students lounging about and exchanging stories with Cherie. I sat down and fell right in with the pace of story and laughter in the group. This is kinship, rugged cousins seeing who can tell the funniest story, our students practicing a form of futurity.

Dimaline’s visit to campus was such a beautiful modeling of kinship and reciprocity for everyone. To laugh is everything. Speaking freely is everything. Bans of books and curricula and of our experiences that narrate who Indigenous people are is an attempt to foreclose on our communities. However, as Dimaline reiterated in formal and informal spaces, our stories are knowledge, and they are embodied—between our ribs.

Dimaline’s recounting of her people’s multiple displacements echoes the realities and histories of many of our Native nations in Oklahoma, where many of our students hail from. Her story resonates deeply with the shared removal from homelands and place, and her poetics of kinship with the land and extended family resonates as well. She preciously tells the young people in the audience, “You are my beautiful responsibility.” Sharing her relational accountability in her books and in person cements our deep respect for her. We see ourselves, we see our community and our experiences represented, and she validates our existence. She is the ultimate auntie.

Kinship care, love, and relational accountability have carried our ancestors through multiple displacements, through dark and past lives.

More importantly, Dimaline keeps lovingly reminding us, our stories are embodied through all our displacements. Everything we needed is packed between our ribs—it is our stories. Our embodied stories cannot be banned, they are memories, experiences, and that which we feel. Although in The Marrow Thieves the government tries to erase our stories and extract our ability to dream for themselves, they cannot fully grasp all the stories we embody. Our stories present themselves judiciously. The story surfaces in the way it needs to in the moment, with a mean twist or a light heart—it’s predicated on what the moment calls for. The moment might call for a story about dreaming or consent or relational accountability.

Dimaline’s work extends to us wormholes to a spatial imaginary with luxurious language bursting with nuance about the land and relationships. She builds the lush promise of community in her writing and in person. In these spatial imaginaries, I believe that kinship, care, love, and relational accountability structure futurity—our simultaneous past, present, and future. These central tenets are a way of being in the world—while it surfaces in critical Indigenous studies, Indigenous practices and values ground it in community. From community to community the kinship practices might look different (or not). But this I believe: kinship care, love, and relational accountability have carried our ancestors through multiple displacements, through dark and past lives. But still they are lives that are well lived, even when to outsiders it just looks we are surviving. All you have to do is crack open one of Dimaline’s novels to encounter these practices.

The transformative power of honest witnessing in a community story is part of the map to the next world. Dimaline’s wayfinding tools are storytelling, dreaming, and recognizing stories of our kin. During her visit, her presence was electric and brilliant, but she is humble, saying her world is small, and she brings these stories from her world. However, her stories pull back the curtain to so many worlds for all of us.

Dimaline’s collection of novels is punchy and on point. In her storywork is a repository of blueprints that guide to and through the next world. She is our sister, our auntie from the north. Jam-packed with stories in a small frame, and sharing the characters our students need. She brought us what we needed, when we needed it. Like that favorite auntie who spoils you. She spoils us with her love in her stories and her love for our young people and elders.

University of Oklahoma