Besieged

When martial law is declared in Korea in winter 2024 by a president seeking to stage an autocoup, the writer is pushed to revisit her teenage years spent under military rule and confront the damage and despair encountered by her family as she approached the cusp of a precarious adulthood.

It is 1979, and martial law slithers in through the shadows when the president—the only one I have known in my thirteen years—is shot to death in the middle of the night. The news arrives with the ringing at my father’s bedside. I open the door to my parents’ bedroom and catch my father’s long, naked legs as he struggles to sit up while holding the receiver to his ear, a scowl between his brows. He soon turns to my mother and says, “Park Chung Hee is dead,” creating a stir that feels strangely like excitement.

In the morning, I walk to school like any other day—across the complex past fourteen rows of apartment buildings, take the footbridge across the main street, to the gate where a squad of five student monitors is lined up, like any other morning, to check every single girl arriving at school: identical in all-black uniforms and one-centimeter-below-the-ear haircuts in the same straight style. Several students are pulled out for wearing the wrong kind of hairpin or missing a badge or name tag or for trying to get away with a pair of tights a shade lighter than opaque black. I make it past them safely, but as soon as I step inside I am assaulted by a shrill chorus of crying that is sweeping across the hallway from room to room. In my classroom, many of the students are weeping with their faces buried in their hands, some clasping their seatmates, moaning, “What’s going to happen to us now?” The dead president’s photo hangs in its usual spot above the blackboard, next to the national flag.

The dead president’s photo hangs in its usual spot above the blackboard, next to the national flag.

It is less than a year since my family moved back from Bangkok and I started middle school here in Seoul, where nothing seems anything like the life I have known. We now live in a flat and gray concrete complex, far away from the hilly neighborhood on the other side of the Han River where I was surrounded by our huge extended family, with my grandfather, who has now passed away, at the center of it all. Here at the new riverside developments, everything seems unfinished—the school gym still under construction and only half the classrooms furnished and occupied, the lawn behind our apartment building bald and barren except for a few transplanted baby trees supported precariously by tripods. The migration—from my old, familiar neighborhood to the dizzying colors of tropical Thailand with its different-looking people and plants and reptiles, then back to a part of Seoul so unlike the city I remember from my childhood—has made everything about my life feel alien, including my parents, who no longer seem to be the same, my father having left his government post and my mother spending many days in bed. So, it makes me wonder: Could this president’s sudden death make my life any stranger?

In 1980 martial law is a rumor rumbling in the distance, making its way into my classroom when I overhear two students chatting in whispers that there’s a riot in this city called Gwangju, and soldiers are arresting everyone out on the streets, even schoolgirls like us. The soldiers punished one girl by cutting off her breasts with a bayonet! My two classmates together let out a shriek. Shush! The one who has been telling the story quickly brings a finger to her lips. We’re not supposed to be talking about this!

In my father’s morning paper I have seen photos accompanied by huge blocks of text in Han characters. Were they of protests? Riots? Are they different? How? But the story I just heard sounds nothing like anything in the news. It seems fake and absurd, like that movie Friday the 13th, which a classmate had boasted about watching on a pirated VHS copy that her brother snuck home but which sounded dumb, at least to me.

In the fall, a new president takes office. Our social studies final tests us not on the chapters covered in our textbook but on the goals and slogans of the new administration, which we have to learn by heart, word for word, no matter how clumsy or awkward: The Realization of Social Justice; the Construction of a Welfare Society; the Creation of an Advanced Nation. My home tutor, a junior in university, sounds dismayed and in despair as she tells me that the new president is one of the generals who drove tanks into the city to take over the country. Just weeks later, the new government announces that tutoring—all learning outside of the school system, in fact—is now banned, effective immediately. I never see my tutor again.

And in the most unexpected turn of events, my father decides to run for a seat in the National Assembly as an opposition-party candidate. “These are new times. Things should be different,” my father tells one of the many visitors suddenly crowding our apartment.

My parents begin spending most days campaigning in his constituency, my grandfather’s hometown three hours away. They often take my brother, who is still in elementary school, but I stay behind, uninterested, perhaps even skeptical. In their absence, I start my third year in middle school. My new homeroom teacher assigns us, in addition to our regular load of homework, a daily quota of ten sheets that must be filled up—from top to bottom, absolutely no margins allowed!—with the studying that we are doing on our own each evening. I am forced to sit at my desk late into the night, the radio my only company, as I copy the lyrics to my favorite songs—by the Beatles, Pink Floyd, Paul Simon, Elton John, every number from the soundtrack of Fame—pretending to be studying from my English textbook, but it’s never easy to reach the required ten pages. Most nights I fall asleep at the desk or curled at the foot of my bed, still in my jeans and T-shirt, then stir awake, panicking that I have yet to finish, dreading the ruler slaps that await at the end of the school day, the pain and the humiliation.

Some days, though, the teacher skips the checking altogether and spirals into these tirades that go on and on about how to live a disciplined life, about some mystical ancient civilization, or about pollutants and nutrients, stuff I can’t quite follow. But sometimes things don’t stop there, and we’re told to take everything out of our bags to search for anything that shouldn’t be there—be it nail polish, photos of celebrities, or whatever it is that we should not be carrying, we’re never sure—and sometimes someone is singled out, for reasons unclear, and is yelled at and slapped, again and again, until she is stumbling down the center aisle then shoved to the floor and kicked, over and over. When he finally stops, he is panting, puffing, as if he has completed a task of tremendous importance, and we all remain completely silent, no one moving, not even the girl on the floor, not even a whimper. It terrifies me that the girl on the floor could have been me, but at the same time I am relieved that it was her and not me. It does not occur to me that there ought to be a law to protect us from this; I have no way of imagining that this can be stopped. Instead, I crumble inside. Nothing to be done. Not here is the one place I want to be.

I am home alone on election day, and I learn from TV that my father has lost. The four of us retreat to our three bedrooms, each one sealed tight, months passing in silence. Until one morning, my mother does not wake up and my father drives her to the ER, telling me to get in the back seat with her. At the hospital, my father chastises me for sobbing, that perhaps I am not the mature and responsible individual that he thought I had grown into. My mother survives, but the fact that she wanted to no longer exist in this world is something that must not be discussed, I come to believe. No one around me has any words to offer me. Guilt and shame become my home, the place I live in.

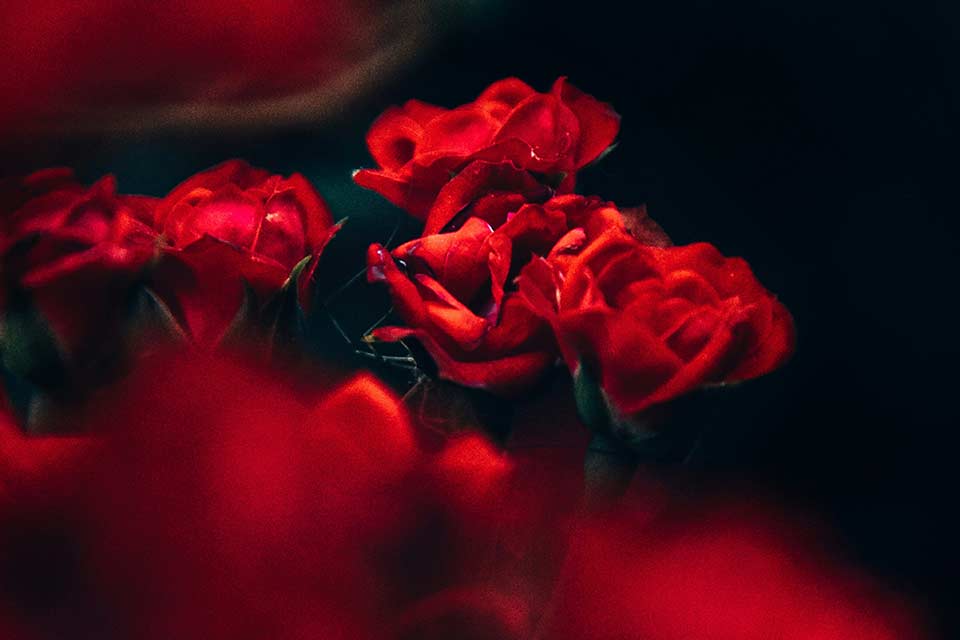

Years later I would look back at this time and find that I have this picture in my mind, of living alone in the apartment, no one else there, somehow persevering on my own or trying to appear that I am persevering, terrified that someone will be able to look inside me and find all the things that I must keep hidden away. I fill my ten daily pages and walk to school each morning, hoping to make it past the student monitors, praying no one will get beaten up. But from this warped memory also emerges a scene that is vivid and accurate, of walking home after school on my birthday, when—upon crossing the footbridge—I notice a huge, overgrown rosebush, their blossoms blood-red, so bright they feel imagined. Have they always been here, this time of the year? Red roses that bloom, full and beautiful, on the day that I was born, something I never knew before.

It is 1986, and martial law is a past we must dig up and look straight in the eye. The upperclassmen in the Korean lit department tell us that we have been living in innocent ignorance and must now go through a painful awakening through reeducation. I have come to college hoping to read literature, hoping to meet someone dashing who reads literature, hoping to find books that speak for all that is entangled inside of me, hoping to be able to put into my own words all that I have kept locked. But the first thing that greets me on campus is the Pocketbook for Freshmen handed out by the Student Council, which contains our academic calendar with a dozen dates marked in red to commemorate the deaths of activist martyrs, students, and laborers who have leaped from windows and rooftops and bridges after setting themselves aflame. At the freshman welcome retreat we learn the liberation dance—which is less a dance and more a martial arts sequence involving militant high kicks—sing protest songs, and drink makgeolli late into the night. Then, in the morning, we are rattled awake for our consciousness-raising session, which requires writing down and reading aloud brutal words of self-criticism.

I run, even if it means I am a selfish, ignorant bourgeois, which, coming from their hard, righteous mouths, sounds worse than a swear word.

I seek shelter at the theater club, the kind that stages dramas in what is considered the Western imperialist tradition. I find peace in the dark nooks backstage, in the wings, in the green room, in the control room up on the third floor with a distant view of the proscenium, where the actors bask under the bright lights.

In the steamy student cafeteria, located on the hill between the literature building and the theater, blown-up photos of scenes from Gwangju serve as a backdrop to all our meals—tanks bulldozing through the crowds, soldiers striking at the protesters with their shields and clubs, streets awash in blood, students in uniforms like the ones I used to wear, cuffed and roped in a chain like bundles of dried fish, rows and rows of coffins, piles and piles of corpses, and this young boy resting his head on his father’s funeral portrait with a faint, complicated glow in his eyes. I cannot bear to look into those eyes. I recognize his hollow grief. I know what it is, but I feel I have no right to feel it myself, I, who has not lost her father; I, who did not get her breasts cut off by soldiers; I, who sat unmoving when my middle school classmate was slapped and kicked, when a fellow freshman stormed into the lecture room shouting, “This is not where we should be! There are students being beat up and taken away as we speak!” I, who have done nothing.

I cannot bear to look into those eyes. I recognize his hollow grief. I know what it is, but I feel I have no right to feel it myself.

On December 3, 2024, when martial law is declared for the first time in forty-five years, it is aired live on national television and streamed real-time on YouTube. By now we have elected eight presidents by direct vote, have sent the culprits of the Gwangju massacre to jail, the democratic movement and its heroes and martyrs, honored and memorialized. Yet I hear—from the mouth of this elected civilian president—that, as of this minute, all political activity will be banned, all press and publications must undergo censorship, all violators of the decree will face arrest without warrant. The words instantly transport me back to the years spent under martial law and its aftermath, as if history has not taken place, as if I have awakened to find that it had all been a dream.

To my son’s surprise and to my own, I start sobbing in front of the TV. This is something I rarely feel entitled to do, not since my father demanded that I stop crying at the ER where we had taken my mother. Is it that girl at the ER who is sobbing, all these years later? I am scared I no longer seem to be where I thought I was, here at home, the place I now want to be, with my son at the cusp of adulthood and my very old cat and my handsome black dog, the family I have now, who have replaced my late, departed family—my father, my mother, my younger brother. I am overcome by a visceral realization that I have so much to lose, that I am where I want to be, I do not want to be anywhere else. It has taken me so long to arrive at this place, but just like that, this place could turn into that same place I wanted to escape.

It has taken me so long to arrive at this place, but just like that, this place could turn into that same place I wanted to escape.

I also recall the petition I signed several months ago, drafted by colleagues at my university in protest of the injustices and the idiocies of this administration. Had I been able to speak up all these years—as a writer, an academic, a citizen—only because I believed it was perfectly safe? I begin to see in my mind flashes of men banging at my door, of being blindfolded and driven away, finding myself locked in a room with no windows, only a single naked-red lightbulb swinging from the ceiling, my head being pushed into a tub of water until my arms flail and flutter then go limp, my shirt ripped open by a bayonet that stabs into my breasts, over and over.

Not now. Not now when I finally want to stay, when I finally want to be here in this place where I am, after everything that I, and this country, have been through.

It is spring 2025, two weeks after the Constitutional Court ruled to oust the president for the unjustified military takeover that violated the principles of the rule of law and democracy. A student in my poetry translation workshop brings in to share with the class the poem “Black Leaf in My Mouth,” by the late Gi Hyeong-do, whose abysmal hopelessness the critic Kim Hyun wished no other Korean poet would share ever again. Not long after publishing this poem, Gi died from a stroke while sitting alone at a late-night showing in a downtown movie theater, a bottle of soju in his hand and covered in his own vomit. As my student reads the last line—“Inside my mouth clings this black leaf, stubborn and desperate, and I am terrified”—I notice the quiver in her voice, the flush in her cheeks. She has spent the past year battling stage-three breast cancer but has returned from winter break wearing a rosy glow instead of her wig. How brave she is, to be able to look straight into the poet’s fear and despair. She talks about how the poem, which centers on an “incident” and the deaths that ensue, resonated with her as she lived through the shock of the short-lived martial law, and we talk about how the poem seems to be about trying, but being unable, or too frightened, to speak. I mention that the line about the young boy bursting into sobs at his father’s funeral, unable to bear being “besieged by the leaves,” was especially vivid for me in the light of our recent experience, but do not go so far as to mention how it transported me back to the steamy cafeteria where I encountered the photo of the little boy in Gwangju with his father’s funeral portrait, whose hollow grief I recognized, yet felt I possessed no right to feel.

Two weeks earlier, on the day of the impeachment ruling, I had heard the roar of the crowd outside the courthouse from my perch on the foot of Mt. Inwang, where I live, next to a fortress built six hundred years ago—back when Korea was a kingdom named Joseon, before any idea of a republic of and by the people was thinkable on this land. The sound from the street traveled uphill, my entire neighborhood booming with the thumping beat of the K-pop hit “Fighting,” its lyrics rewritten for the occasion—“Oust Him!” Even protest songs are fun and trendy now. The liberation dance is an antiquity remembered by few. The trial at the Constitutional Court revealed, however, that my fears had not been mere paranoia; the plans to siege the state were very much real, ready to be executed. The ground could have crumbled away under my feet. But it is now time, and on TV the judge begins to read the verdict, the exposition clear and taut, perfectly cadenced, as real as anything in this world.

I am where I want to be, here and nowhere else, and it feels more real than anything, perhaps for the very first time.

Ewha Womans University, Seoul