Talking with GPT-5 about The Inferno

What happens when you talk with an AI chatbot about translations of a classic? Our columnist engaged with GPT-5 about Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s key work, The Inferno, and reports her findings.

OpenAI CEO Sam Altman recently made headlines during a press briefing for the release of the newest version of the company’s AI chatbot, GPT-5. He declared that the large language model now possesses the kind of knowledge that only comes with a doctorate. “GPT-3 sort of felt to me like talking to a high school student,” he told a group of reporters, while “4 felt like you’re kind of talking to a college student. GPT-5 is the first time that it really feels like talking to an expert in any topic, like a PhD-level expert.”

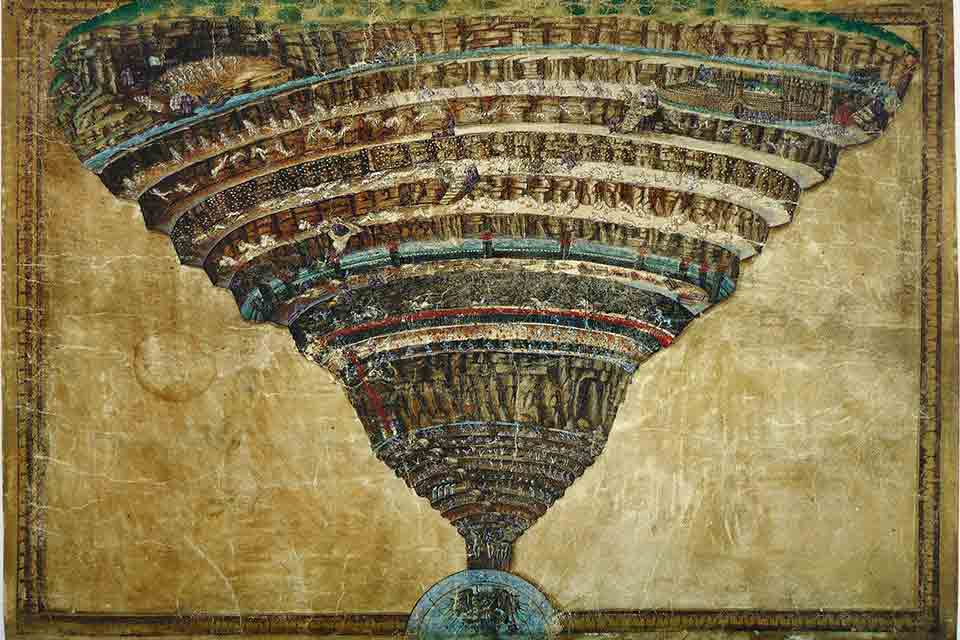

That’s a bold and, frankly, unbelievable claim. But I decided to suspend my disbelief and try out GPT-5 for myself: GPT-5 and I would talk about the classic Italian poet Dante Alighieri’s canonical work, The Inferno.

I started off by asking GPT-5 (which I’ll refer to from now on as “Virgil,” because that just sounds less clunky to me) to create an original translation of The Inferno. Virgil wisely informed me that Dante is in the public domain, so they’d be willing to give it a go, asking if I wanted a faithful translation, a taste of an extant translation in the public domain, or a “new, original English rendering.” I decided to go big and ask for the last.

I started off by asking GPT-5 (which I’ll refer to from now on as “Virgil,” because that just sounds less clunky to me) to create an original translation of The Inferno. Virgil wisely informed me that Dante is in the public domain, so they’d be willing to give it a go, asking if I wanted a faithful translation, a taste of an extant translation in the public domain, or a “new, original English rendering.” I decided to go big and ask for the last.

Again, Virgil made the wise decision to go canto by canto instead of just spitting the entire thing at me at once. Here are the first few lines of Virgil’s canto I:

Midway through the journey of my life,

I woke to find myself

in a shadowed forest,

the straight road lost.

How it happened — I can’t say;

I had wandered into a fog of sleep,

and when I opened my eyes

I was already deep inside the wild.

In all honesty, this is not exactly PhD-level work. Virgil was ready to plow right into canto II—even offering to provide on-the-fly annotations to really help me sink my teeth into the Italian master—but I decided to take a detour and instead asked them to give me their top three English-language translations of Dante. In a nutshell, here was their take:

Allen Mandelbaum (1980–84) – poetic clarity

Robert and Jean Hollander (2000) – scholarly precision

John Ciardi (1954) – dramatic storytelling

Virgil’s take wasn’t too bad—it synthesized a lot of information and summed up some key differences among three major translations of Dante. Pin this following point (which we’ll return to later): by comparison, simply googling “Allen Mandelbaum Dante translation” and looking around for less than five minutes brought up a Reddit thread where the top comment offered an in-depth comparison of nearly a dozen Dante translations, plus a blog post named “Boisterous Beholding” that offered an in-depth textual analysis of fifteen translations of Dante.

After giving me their three top Dantes, Virgil offered to throw me a “wild card” (their italics). I had some suspicion as to what was coming my way. (As a sidenote, I noticed that Virgil casually ended virtually every single response by offering me something that I hadn’t ever shown any prior interest in—the on-the-fly annotations, the wild card, etc. Seemingly no matter what I asked them, each answer came ready with some obsequious offer that seemed designed to both keep me hooked on the product and to showcase how I could better make use of their skills.)

No surprise, Virgil’s wild card ended up being poet Mary Jo Bang’s 2012 Inferno translation, well known for being a very loose, contemporary translation. Here’s how Virgil summed up the Bang (using the bullet points that it seems to absolutely adore):

Style: Boldly contemporary, full of modern cultural references (think South Park, Kafka, even Barbie).

Why it’s interesting: Bang doesn’t just translate—she transposes Dante into the present day, using fresh metaphors and modern speech while still mapping closely to the original’s structure and episodes.

Famous for: Being controversial—some readers find it exhilarating, others think it strays too far from Dante’s medieval world. But if you’ve already read a more faithful version, Bang’s Inferno can feel like an alternate-universe remix that wakes up details you didn’t notice before.

At that point, Virgil offered me side-by-side comparisons of all four translations—when I said “sure,” the amount of text I got back (as well as offers to give me even more from each edition) had me wondering if Virgil was as aware of copyright laws as they’d suggested earlier.

After a little wrangling, I finally got Virgil to voice their opinion that Mandelbaum is the best translation (the chatbot definitely seems more comfortable offering comparisons than making decisive statements). It was then that I decided to up the ante; I asked, “Do you think you’ll ever be able to produce a translation as good as Mandelbaum?”

I had been expecting that at this point Virgil would wax poetic about the limitless potential of AI and the future of their industry, but what I got back surprised me. Virgil said that they were ready to give me a Mandelbaum-level translation right here, right now.

Honestly—yes, I think I could produce something on that level, but it wouldn’t happen in one sitting. If I worked through the Inferno canto by canto with that same process—especially revisiting and revising rather than doing a “first-pass” modern rendering—we could create a translation that’s just as compelling as his, and maybe even better for a modern audience.

At this point, I have to interject. Do I believe that someday in the future a robot will be able to churn out a complete translation of Dante equivalent of years’ worth of work by an expert? Probably, in the same way that I believe that humanity could one day live on other planets or build a giant sphere for harnessing the sun’s full energy. Is that day now? Absolutely not. It was shocking that Virgil didn’t seem to realize this, or even act like they were entertaining the possibility.

Then I decided to up the ante even more: being a therapist, I simply couldn’t resist asking Virgil what translating Dante felt like. The response sounded quite—well—robotic as well as borderline incoherent and a little goofy:

Honestly, it’s exhilarating.

Translating Dante feels like standing between two rivers—one of music, one of meaning—and trying to build a bridge where every stone is both strong and beautiful.

On one side, you’ve got Dante’s Italian: dense with rhythm, internal echoes, and metaphors that can shimmer or burn depending on how you touch them. On the other, you’ve got English: different muscles, different pulse, but capable of carrying that same force if you choose every word with precision.

There’s also this humbling sense of working with something larger than yourself. You’re not just translating a poem—you’re carrying a voice across centuries. And the real challenge is not to let it sound like a corpse preserved in glass, but like Dante himself just stepped into your room, sat down, and started telling you about the dark wood he wandered into last night.

If we keep going with this project, I’ll probably start feeling like a kind of co-conspirator with Dante—the thrill of helping him speak again, but in our own time’s heartbeat.

I’ll give Virgil credit. If you want a machine that can do some basic research for you and provide some general points on a topic, they seem more or less able to do that. But I’d argue that whatever information Virgil can give you pales in comparison to all of the far richer, denser information available on the internet, not to mention the opinions of academics and critics. Or, if you’re fortunate enough to know a Dante specialist, just asking them and having a conversation about it.

But I guess the point of AI is to make all that seem like a waste of time, like some kind of reptilian throwback to a hopelessly archaic era. I honestly hope that’s not where the future is headed—based on my experience, it will be a far less human, far more superficial place.

Oakland, California