The Voynich Manuscript

What does it say about our society that we are so fascinated by an object that seems to retain a meaning that nobody on earth can access? In her ongoing column, Veronica Esposito looks at a long-baffling manuscript, the deciphering of which might be more akin to codebreaking than translating.

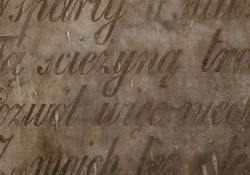

For the past few weeks I’ve been falling down the rabbit hole of the Voynich Manuscript. This is something many of you have probably heard of (particularly those of you who read my last column). It’s one of the world’s most famous untranslated documents, dating back some six hundred years and having been introduced to the modern world when it was uncovered by a Polish merchant named Wilfrid Voynich in 1912. Clues within the document itself, with a big assist from carbon dating, indicate that it was likely created early in the fifteenth century, and the historical record has shown that, through its long existence, this enigma has fascinated the human mind for centuries. None so far have uncovered its secrets.

One of the strangest things I have learned about the Voynich Manuscript is that, for decades now, it has been an object of fascination for the US National Security Agency. Throughout the 2010s, the NSA declassified numerous documents that it had commissioned on the Voynich Manuscript, including some monograph-length reports made by experts in fields like cryptography. Although it is not exactly clear why the NSA is obsessed by this document, it has been suggested that managing to take possession of a code that no one else can break would be of great value.

This NSA fixation on the Voynich Manuscript would be just the latest in a long, long history of humans trying to use secret codes to beneficial ends. The field of cryptography began to flourish right around the time the Voynich Manuscript was being composed—according to an exhibition at the Folger Library titled Decoding the Renaissance, the first document written in Europe on the subject of cryptography arrived in the 1400s, right alongside Voynich. As codes and cyphers became increasingly fashionable, they were quickly turned to purposes of war, one of their first material uses.

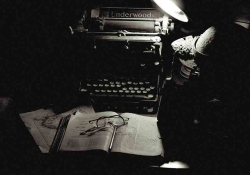

This continued to the modern period: for instance, William Friedman, a cryptographer who began his career trying to prove that Francis Bacon was the real author of Shakespeare’s plays, eventually opened up Japan’s code language in the Second World War, a major victory for the Allies. Friedman later tried to crack the Voynich Manuscript, but he failed at it, as did the pioneering computer scientist (and wartime codebreaker) Alan Turing, a Holy Roman emperor (more on him in a moment), and countless other scholars of diverse disciplines. Codes continue to be valuable to human beings today, not only for military purposes but also for tech giants looking for ways to safely store all our precious data. But there are also less-tangible reasons that we remain fixated on pieces of writing that resist our efforts to read them.

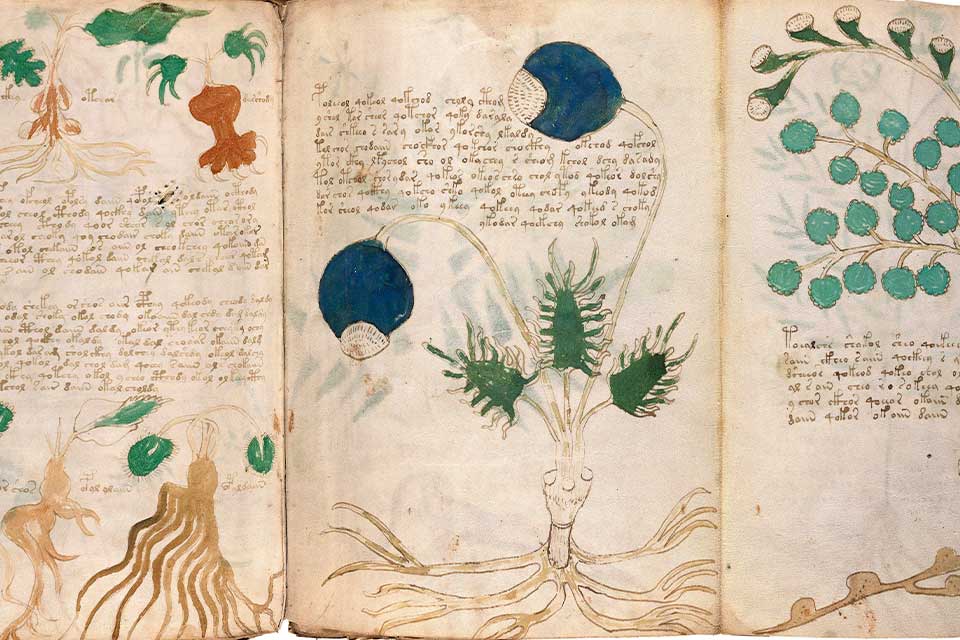

Some facts about this document. It is currently owned by and housed at Yale University, which published a facsimile edition of the book in 2016, letting potentially anyone attempt to crack the Voynich code. It is about 240 pages long and believed to be about thirty-five thousand words in length (assuming that we’re right that it’s composed in a language at all). It is thought to have originated somewhere in central Europe; analysis has uncovered the handiwork of probably five different scribes who placed the characters onto its pages, and no one has ever discovered another document that uses a character scheme like that found in this manuscript.

The historical record shows that it is likely that, somewhere around 1600, it came into the possession of emperor Rudolf II, alternatively seen as a political blunderer who tripped into starting the Thirty Years’ War and a patron of the arts who helped the Renaissance flourish. Rudolf, a lover of the occult who once received a horoscope from Nostradamus, is the first documented owner of the manuscript that we are aware of, and he reportedly paid 600 gold ducats, or over $100,000, for it. (Although the record is unclear if he was just buying the manuscript or received other artifacts in that transaction.) Rudolf was something of a collector of arcana and spent significant sums on weird books, sometimes spending far more than is reported for the Voynich Manuscript. After him, it passed through the hands of numerous owners, eventually coming into the possession of Jesuits in Italy, where it remained hidden throughout multiple confiscations of Jesuit property until Voynich himself purchased it in a highly secret sale. In 1969 book dealer Hans P. Kraus donated it to Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, along with numerous collateral documents.

Statistical analysis of the manuscript has indicated that it may be prose, or it may be something else (poetry, perhaps?), that the pages tend to have recognizable subjects, that it may be a blend of two separate texts, that the pages seem to be in order, that word order in the text is strangely weaker than in most other languages, and that the text likely lacks vowels or punctuation. Some evidence has been brought forth that it is a hoax, although most scholars of this document believe that the evidence points to its authenticity.

In a strangely fascinating 2017 article for the Times Literary Supplement, Nicholas Gibbs published an essay in which he boldly declared his smashing success in cracking the manuscript by using a curious method. He first made a close study of the book’s many illustrations, thus allowing him to fashion a sort of “translation.”

By now, it was more or less clear what the Voynich Manuscript is: a reference book of selected remedies lifted from the standard treatises of the medieval period, an instruction manual for the health and wellbeing of the more well-to-do women in society, which was quite possibly tailored to a single individual.

Gibbs further conjectured, based on the widespread use of Latin ligatures in the medieval period, that “each character in the Voynich manuscript represented an abbreviated word and not a letter” (italics in original). Alas, medievalists quickly shot Gibbs down, with several indicating that his proposed solution had long since been considered and rejected; Medieval Academy of America director Lisa Fagin Davis dealt the final blow to Gibbs’s theory, saying, “Frankly I’m a little surprised the TLS published it. . . . If they had simply sent to it to the Beinecke Library, they would have rebutted it in a heartbeat.”

More recently, web communities like that at voynich.ninja track the latest theories and developments in trying to translate this tome, even offering some potential translations of pages. Artificial intelligence has also increasingly been used to try to open up the book’s secrets. One imagines that, if this book ever is translated, it may not come all at once but in little bits and pieces over the years, until at last a composite picture of its contents is formed.

The Voynich Manuscript poses an interesting limit case for notions of untranslatability.

The Voynich Manuscript poses an interesting limit case for notions of untranslatability. Typically, a document is considered untranslatable when at least some number of people has some sense of what the original document intends to say—the untranslatability comes when there are things that are difficult to transport from one language to another. But here, the difference is that no one actually knows what this book says, meaning that deciphering the Voynich manuscript might be seen as more akin to codebreaking than translating. Were the code ever to be broken, literary translators might then be brought in to improve upon what would at that point be a very rough translation of the text’s semantic meaning.

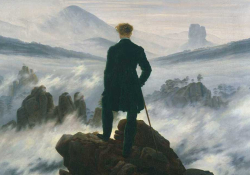

The unknowability of the Voynich Manuscript is on a different ontological plane than that of your typical untranslatable text. We don’t even necessarily know that it says anything at all, and we have used various methods—statistical methods, samples of the document’s molecular composition, intuitions drawn from its illustrations, and general knowledge of the period it was likely created in—to try and X-ray in past its intelligibility to gain some foggy sense of what lies beneath. As a society, we have decided that breaking open its mysteries is worthy of substantial resources, which, as Robyn Creswell points out, is one of the fundamental questions of all translations, and one that impinges in some basic way on the notion of translatability:

As any experienced translator will tell you, if you can’t translate a word, try the sentence or line, and if you can’t translate that, move on to the paragraph or stanza. We might generalize the point by saying that the translator’s first and most consequential choices, the ones that set limits on all the rest, have less to do with words than with texts, authors, and even languages. Which ones are worth putting into English, and why?

When it comes to the Voynich Manuscript, the “why” inheres more in its value as an object of mystery than in the semantic meaning hidden in the text. Were the book ever to be translated, it would likely be some kind of medieval treatise on the healing powers of herbs and such—hardly the kind of thing many contemporary readers would pore over. But saying we had cracked a mystery that for centuries has tempted the likes of geniuses and the immensely rich and powerful—that would be of inestimable value to us.

What does it say about our society that we are so fascinated by an object which seems to retain a meaning nobody on earth can access? Writing in the Washington Post, Lisa Fagin Davis suggests that it is about our desire to be in relationship with objects that absorb our need for meaning-making:

Like modern-day Newbolds, we all want to know what the Voynich means. But most would-be interpreters make the same mistake as Newbold: By beginning with their own preconceptions of what they want the Voynich to be, their conclusions take them further from the truth rather than nearer. Their attempts to demystify the medieval past only serve to mystify it further, making the Voynich into a telling avatar of our vexed relationship with the past.

Our attempts to crack the Voynich code speak to a given era’s relationship with notions of the unknown.

Just as our translation preoccupations for a given era speak to the wider social and economic relationships that said translation exists within, our attempts to crack the Voynich code speak to a given era’s relationship with notions of the unknown. Thus, wartime codebreakers like Friedman and Turing gave way to organizations like the NSA and formalized academic inquiry, which themselves are now being supplanted by codebreaking web communities and the use of artificial intelligence. These are the tools we use to bring meaning to the unknown, and their application to the Voynich Manuscript reflects the ways we try to construct the narratives that provide structure to our society.

Given all the time that has passed, it seems unlikely that anyone ever will decode the Voynich Manuscript, and so I would like to introduce the admittedly somewhat risible idea that, in the end, an ekphrastic translation might best serve this document. Probably, a more straight translation of the manuscript would be a decidedly unsatisfying conclusion to one of the world’s great mysteries. Whatever satisfaction we will get from this book is more likely to come from seeing how it was broken open than in knowing its contents. Perhaps we would do better, then, by a translation that was not faithful to the text itself but instead to the layers of meaning that have accumulated around the manuscript in all the many years of human sacrifice and attention which have been granted to it. Ultimately, this might be a much more fitting and enjoyable experience.

Oakland, California