Sehnsucht

bpk Bildagentur / Hamburger Kunsthalle, SHK / Elke Walford / Art Resource, NY

What is sehnsucht, and why hasn’t it taken root in US culture? Veronica Esposito explores the meaning of the word and its use across international culture in her continuing column on untranslatable words.

The word nostalgia was coined in 1688 by a Swiss physician named Johannes Hofer, describing the feelings of homesickness experienced by mercenary soldiers. It entered English in 1756 as a byword for homesickness, and it has since come to possess the following definition: “a wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition” (Merriam-Webster). Throughout the nineteenth century, nostalgia caught on across Europe as Romanticism swept the continent, perhaps because the dislocation inherent to modernization made it more and more common for people to long for unattainable things, like bygone times or the places they originally came from.

Coined from the Greek, nostalgia is readily translatable to major European languages, and it usually features in these languages as a cognate extremely similar to the English. Thus it is a widely understood concept and something that unites English speakers with our cousins throughout Europe. However, while nostalgia is broadly disseminated, that has not prevented many European languages from developing words that are roughly similar to nostalgia but that differ from it in very important ways. Including words like the Portuguese saudade, the Welsh hiraeth, and the Romanian dor, these words tend to be very strongly tied to a national consciousness and have no good English translation.

One such word is the German sehnsucht, which derives from sehnen (to yearn) and sucht (addiction, craving). I have seen this word translated simply as “yearning” or “desire,” or elaborated to add that the yearning is painful, and that it is a yearning for a particular thing that is unattainable. The term is often used in relationship to homesickness, particularly the desire of Germans to return to their homeland. German scholar Susanne Scheibe and her colleagues describe it as “captur[ing] individual and collective thoughts and feelings about one’s optimal or utopian life . . . an intense desire for alternative states and realizations of life” (“Toward a Developmental Psychology of Sehnsucht [Life Longings]”). C. S. Lewis has been widely discussed for using the term to denote spiritual longing, also conflating it with the joy that can come from longing for something that cannot be had.

For Schiller, it is the feeling of wonder that gets us there.

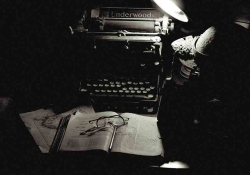

Although sehnsucht is possibly derived from the German language of the Middle Ages, which would date its origins around 1100 to 1350 AD, the word became truly predominant in the Romantic period, when many renowned writers, musicians, painters, and philosophers harnessed their creative powers in attempts to capture its essence. For instance, in the great German playwright Friedrich Schiller’s proto-Romantic poem “Sehnsucht,” he explores the desire that yearns toward creative expression; he posits an adventurer pulling toward some idealized, beautiful land of eternal sun. For Schiller, it is the feeling of wonder that gets us there.

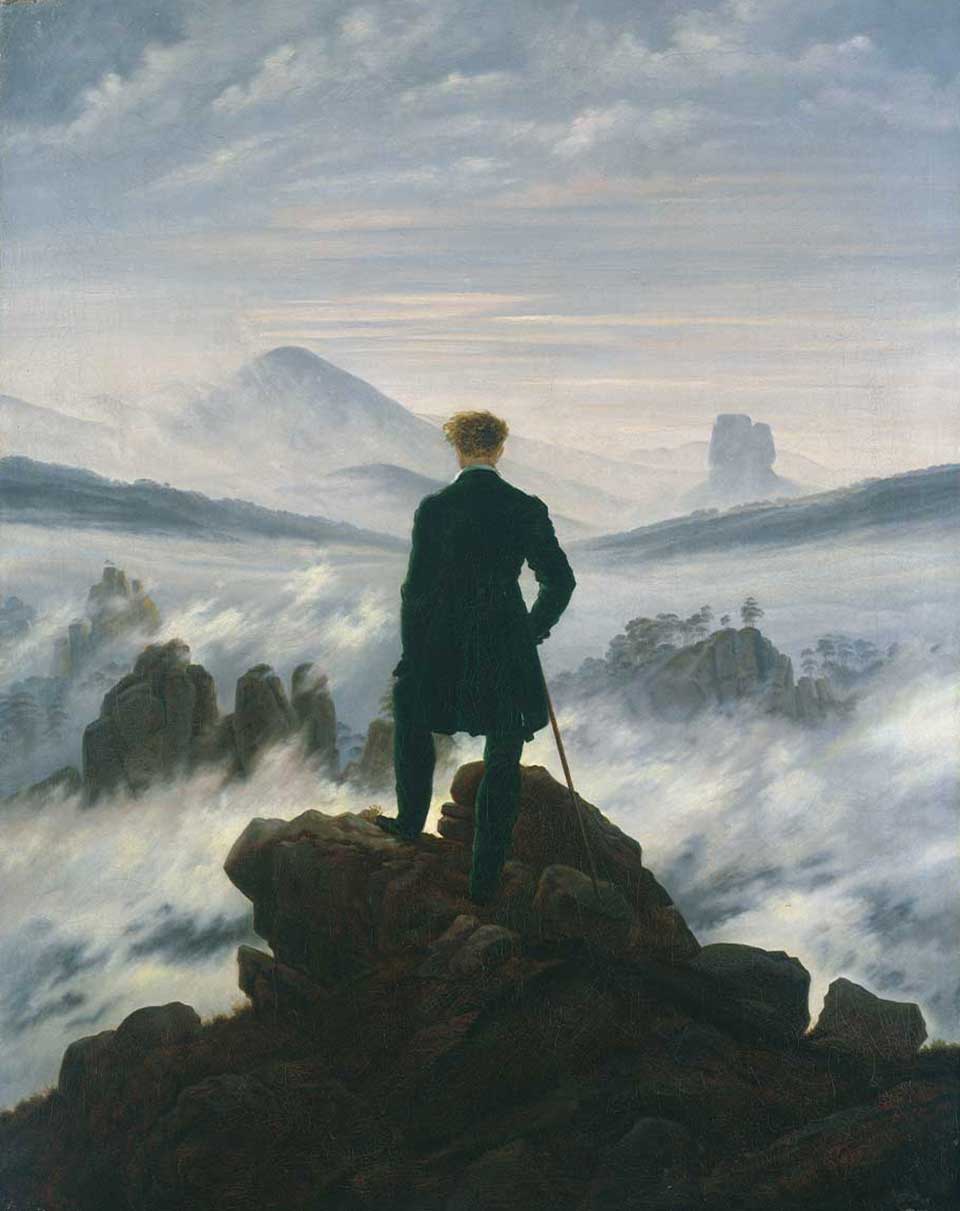

Schiller’s poem is one of the first attempts to explain just what sehnsucht means and why it is so compelling. The concept also features quite centrally in the work of Schiller’s contemporary, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, as well as in the art of German painter Caspar David Friedrich; the latter’s iconic piece Wanderer above the Sea of Fog—showing a man firmly standing on a jagged boulder while facing a churning, misting sea—is probably one of the most famous depictions of sehnsucht ever made. The list of creatives who explored the concept in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries goes on and on, including the likes of Novalis and E. T. A. Hoffmann as well as celebrated poets like Joseph von Eichendorff and Detlev von Liliencron.

This list also includes many musicians. Both Schiller’s and Goethe’s sehnsucht poems have been set to music numerous times by composers like Wagner, Beethoven, Schubert, and Tchaikovsky, and indeed sehnsucht has provided much grist for musicians over the ages. This includes the contemporary era: the word inspired German and Swiss metal bands—Rammstein and Lacrimosa, respectively—in the 1990s and 2000s, both of whom titled an album after it. Judging from the success of their music, sehnsucht remains a powerful idea: in 1998 Rammstein’s album achieved the remarkable feat of becoming the only German-language album to ever reach platinum status in the US—meaning that it sold over one million copies—and the band has just released a twenty-fifth-anniversary edition of the album. For the title track, the band creates an epic, apocalyptic-sounding song about longing for a lost love—like the album it features on, the song is at once abrasive, vulnerable, and mystical, translating that sentiment of longing into something broadly appealing to twenty-first-century minds.

Based on the success of artworks inspired by the concept of sehnsucht, it is an idea that seems to resonate, even if it is difficult to translate precisely outside of a German context. In one of their many scientific papers attempting to empirically study this idea, Susanne Scheibe and her colleagues examined the sehnsucht experiences of well over one thousand individuals, ranging from eighteen years of age to eighty-one; specifically, the study wanted to examine the similarities and differences between how Germans and Americans experience sehnsucht. It found that, while both German and American participants were adept at stating the things they longed for, the Germans tended to name less attainable things, while the Americans named more concrete, readily attainable things. In explaining their findings, the authors noted that America’s frontier spirit promotes ideas of independence, whereas Germany’s longer history and stronger social institutions favor ideas of interdependence. Thus, Germans are possibly more prone to accepting that some things are unattainable, compared to Americans, and thus more comfortable longing for things that can’t be had.

In explaining the purpose of their research, the authors write that “Sehnsucht has important developmental functions for life planning and management”; namely, that these yearnings “provide a sense of directionality” and “help to compensate for lost or unattainable aspects of their lives.” They go on to suggest that such yearnings can give a sense of continuity and meaning to a life, indicating that this concept serves a vital function over our life spans. However, they also cautioned, “if life longings are too intense and uncontrollable, a sense of frustration and despair may prevail, compromising a person’s overall quality of life. Participants with strong life longings were found to have lower well-being, higher negative affectivity, and an overall stronger desire for change in their lives.” Scheibe and her colleagues have also written, “There can be desires in life that are so essential to a person’s self-concept and well-being that they cannot easily be relinquished. They likely have to be used adaptively or else will compromise well-being.”

An example of one such person who did not use such desires adaptively is found in the protagonist of the Lebanese film A Play Entitled Sehnsucht. Released in 2011 by the filmmaker Badran Roy Badran (his first and, so far, only movie), A Play Entitled Sehnsucht is a strange film about which there is little information. It almost reads like an urban legend or something out of some bizarre postmodern novel, but apparently it is real. Sometimes referred to as the first experimental film in Lebanese cinema, it is said that during the film’s premiere the director caused a scene, decrying the nation’s politicians for the lengthy, brutal civil war that killed over one hundred thousand Lebanese across fifteen years.

The plot of A Play Entitled Sehnsucht involves a Lebanese astronomer who claims he saw a planet explode in 1975; throughout the movie, the astronomer is in an insane asylum, and much of the movie’s action has to do with his treatment by none other than a German hypnotist. The film has been taken as an allegory for the awfulness of the civil war that tore Lebanon apart—the civil war began in 1975, the same year that the movie’s protagonist believes he saw the exploding planet. In an enthusiastic piece for Agenda Culturel, Joumana El Hayek interprets it as a film about, among other things, the loss of childhood innocence, and, in a now-defunct Wikipedia page archived at Wikibin, the film is said to “reflect the incurable self-destructive nostalgic desire that Lebanon suffers from.”

Clearly, sehnsucht is a concept that has remained relevant and vital to artists and storytellers around the world, and has continued to serve an important purpose across the human life span, even though the world has changed radically in the two hundred or so years since the word became broadly used. In spite of that, however, although some critics have attempted to write about sehnsucht in American literature, the concept remains little-explored in regard to writing on our shores, perhaps because of the American can-do spirit that Scheibe and her colleagues referenced.

Attempts have been made to link it to purely American stories like The Great Gatsby as well as quintessentially American writers like Vladimir Nabokov, Saul Bellow, and Ann Beattie, but the concept has not really caught on among literary circles over here. Perhaps we are still waiting for our truly groundbreaking novel, movie, or TV series of sehnsucht, or perhaps this is simply a concept that, while understandable in some meaningful way by speakers of English, refuses to take root in our language and culture.

Oakland, California