Where Are the Translation Collaborations?

The image of the translator is often that of the lonely, intrepid soul working endless hours, accompanied only by stacks of books, but our columnist thinks the reality is otherwise—that translators are gregarious, supportive individuals who thrive on literary community. Though some collaborative efforts may have passed, might we be in a reemerging era of collaborative translation?

In her fascinating paper, “A Flight of Tokarczuk Translators,” researcher Karolina Siwek describes a meeting in Gdańsk, Poland, of numerous translators from within the community of some ninety wordsmiths that have dedicated themselves to Polish author Olga Tokarczuk, representing thirty-seven languages altogether. According to Siwek, this community of Tokarczuk translators is emblematic of the many benefits to be had from collaboration in translation. “The idea of collaboration,” she concludes,

known from the time of the translation of the Bible, is returning to favor in a new refreshed form. It remains to be seen whether literary translation will benefit from it on a large scale. Nevertheless, the theory condemning teamwork as a death knell to creativity discourages putting it into practice. What benefit can collaboration and cooperation during the translation process bring to literary translation? Perhaps translations created in this way have a chance to be close to the canonical ones.

Tokarczuk’s convening of translators is reminiscent of the gatherings that Günter Grass would hold of his translators.

Tokarczuk’s convening of translators is reminiscent of the gatherings that German author Günter Grass would hold of his translators—Grass even went so far as to stipulate that publishers make themselves contractually obliged to pay airfare for translators to attend these convenings. Here is how translator and researcher Joanna Trzeciak Huss describes the practice:

From 1976 till his death in 2015 [Grass] engaged in the practice of convening all of his translators shortly after the publications of a new work for a question-and-answer retreat that lasted three to four days. . . . Grass required that publishers of his translations insert a clause into the contract with the translator that the publisher would provide airfare for the translator to attend a seminar with Grass where the author would make himself available to answer translators’ questions (Grass would cover the cost of accommodations for those attending). . . . Grass was rarely interventionist, but rather would provide help for translators in understanding elements, particularly realia, peculiar to German culture. . . . What was truly groundbreaking was the opportunity for translators to collaborate not only with the author, but among themselves, which is especially fruitful when the languages in question are closely related (e.g., the Scandinavian languages) and thus may permit common solutions.

Huss concludes that the “significance of inter-translator, translinguistic collaboration cannot be overstated” and argues that in the age of the internet, such collaboration is on the rise. Siwek strikes a similar tone in favor of internet-based collaboration—she discusses a Zoom convening of Tokarczuk’s translators and encourages such forms of collaboration.

This is one kind of translation collaboration, involving groups of translators, usually orchestrated around a single author. Siwek argues that this kind of collaboration is very different from those based around the relationship between an author and their translator—this she sees as much more hierarchical. In a fascinating paper, the French translator and essayist Patrick Hersant describes a full spectrum of various kinds of author-translator relationships. He quotes William Faulkner to describe one end of the spectrum, the completely hands-off author: “William Faulkner [said] to Maurice-Edgar Coindreau, who was afraid of not doing justice to the American novelist: ‘Why are you concerned about it? If there were passages which caused you problems, you could simply have skipped them.’”

Further down the spectrum, on the more interventionist side, Hersant locates Italian author Claudio Magris, who annotates his manuscripts with elaborate notes for future translators—Hersant speculates that this might cause some anxiety: “one can imagine the uneasiness or apprehension a translator might feel upon discovering such a list.” He also raises the notion of “closelaborations,” a neologism that he credits to Cuban author Guillermo Cabrera Infante, who invented it to describe his in-depth work alongside his English-language translator, Suzanne Jill Levine. However, Hersant cautions that this concept is not so much about Cabrera Infante celebrating the translator as it is marking his authorial territory: “Cabrera Infante intends less to pay tribute to his translator than to clearly signal his own participation.”

If the forms of collaboration between author and translator tend to range among various degrees of hierarchy, teams of translators working in collaboration offer a much wider and more diverse array of possibilities. Siwek mentions several. For instance, there is the duo who translated the famous Polish author Witold Gombrowicz’s major novels Ferdydurke and Ślub—one was a native speaker of Polish, the other of Spanish, and together they created acclaimed Spanish-language editions of the classic Polish works. Then there was the team of twenty-one translators who worked on bringing Matthew Kneale’s novel English Passengers into Polish—one translator for each of the book’s twenty-one narrators. There’s also the case of the Przebinda family, who used the intergenerational knowledge of two parents and their child to create a unique translation of Mikhail Bulgakov’s Russian classic The Master and Margarita.

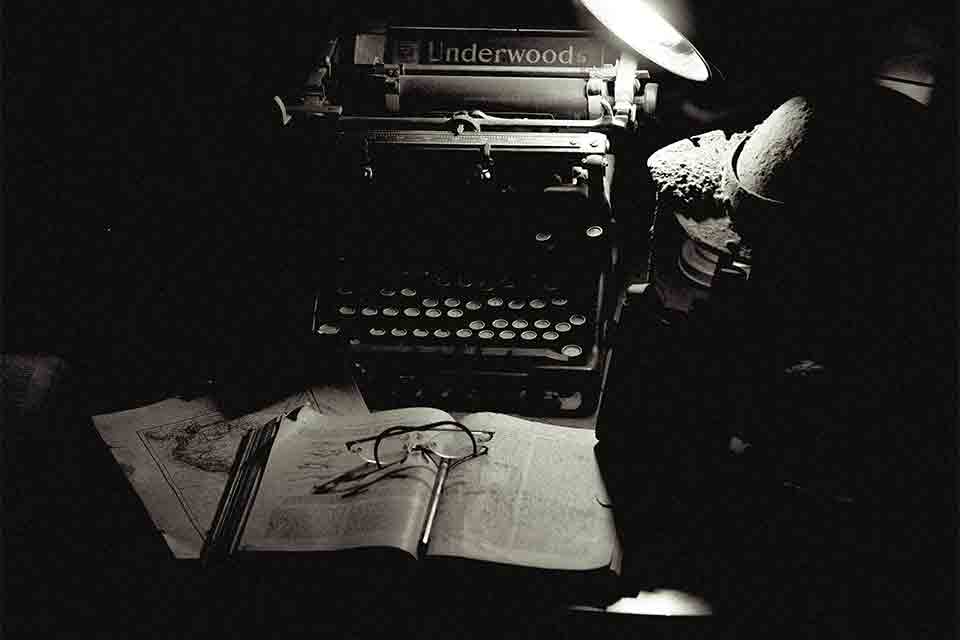

Siwek’s and Hersant’s essays are fascinating for how they offer glimpses into the kinds of collaboration that make translation possible—not a subject that often takes precedence when looking at translated literature. The image of the translator is often that of the lonely, intrepid soul working endless hours, accompanied only by stacks of books, but I think the reality is otherwise. I have always known translators to be gregarious individuals who thrive on the community aspect of a literary industry that, in the words of one translator, is “by nature [a] gossip-ridden industry.” They are greatly supportive of one another and rely on translation communities for many forms of assistance.

That assistance is not just in the form of finding the ideal phrasing for a tricky passage; it often permeates the business side of things, which more and more is the purview of translators looking to make their career. Here we see translators gather together, regardless of which author they translate or which languages they translate from. Speaking with Nathan Scott McNamara in the Los Angeles Review of Books, translator Julia Sanches discussed the translation collective Cedilla & Co, of which she was a part, explaining some of these kinds of benefits that can come from translators working collaboratively.

One of my personal motivations for trying this model was to democratize how translations were submitted and therefore, hopefully, published; making sure editors across publishing houses had the opportunity to judge a project on its literary merit rather than ruling them out ahead of time because said publisher doesn’t usually publish translations. The idea was to target editors outside the usual suspects across a wide range of publishing houses, which is how agents approach the submission process.

Unfortunately, it seems that Cedilla & Co is now a thing of the past.

I am still aware of groups of translators banding together to provide moral, business, and linguistic support, based around things like bookstores in common, geographic proximity, and shared authors, but I do wonder where exactly are the translation collectives today, be it along the lines of Cedilla or the flight of Tokarczuk translators? Surely papers by the likes of Siwek, Huss, and Hersant—to say nothing of the experiences of Sanches—point to the many advantages to be gained from building translation communities.

Siwek ends her essay suggesting that we are in the midst of the reemergence of an era of collaborative translation:

It turns out that the image of a literary translator working in seclusion and isolation is a thing of the past. If there is an opportunity to get help, they are eager to use it. New technologies and ease of communication are conducive to frequent telephone, emails and social media contacts. Translators can be in constant touch. The idea of collaboration, known from the time of the translation of the Bible, is returning to favor in a new refreshed form.

I hope she is right.

Oakland, California

Editorial note: This essay was modified to delete a reference to the Third Coast Translators Collective that said it “appears to be defunct.” We regret the error. Happily, the TCTC is alive and well and will be featured on the WLT Weekly in August.

Editorial note: For a fictional take on a gathering of an author’s translators, enjoy The Extinction of Irena Rey, a novel by one of Tokarczuk’s translators, Jennifer Croft. Reviewing the novel for WLT, Hannah Weber concludes that “Croft has reinvented ecofiction with this seductive, erudite, and terribly funny tale about ‘book people’” (March 2024).