The Chinese Cinematic Cosmos

The author describes how a “heady concoction” of East Asian cinematic stories inspired his own work as a storyteller.

As a young adult, Chinese-language films became something of a lifeline to me. I’d spent my teenage years adrift, with the barest thread of a relationship to my heritage or cultural identity. But then I moved to LA for college and found myself careening into an entire cinematic cosmos filled with worlds that felt, at once, intimate and defamiliarized. I became mesmerized by a whole generation of actors and directors as I barreled through my undergraduate film curriculum, yearning to apprehend the core of my own storytelling impulses.

The relationship between fiction and film is usually presumed to be unidirectional, a screen adaptation of a written narrative as the most common archetype. But for me, the process unfolded in reverse, the images, characters, and ideas I internalized as a film student gestating for nearly two decades before finally emerging in fictional form.

My debut novel, Masquerade (Tin House, 2024), is, in many ways, a quintessentially New York story, but a significant portion of the narrative unfolds in Shanghai—both the contemporary city and a simulacrum of a bygone era. In writing this twinned tale of identity and longing, the search for meaning amid the senselessness of the past and present, I tapped into a heady concoction of stories that had long ago begun brewing inside me, filled with bits and bobs of the films that have moved me most.

The titles below are distinctive portraits of China, Hong Kong, or Taiwan, rendered with panache by a visionary artist, each a world unto itself. I’ve returned to these films countless times over the years, taking inspiration from their memorable characters and indelible settings, examining how even the mundane can become romantic, mysterious, or macabre by framing, pace, and juxtaposition. I hope they may strike a chord with you, too, no matter your preferred medium or how you position your stake in storytelling.

The Terrorizers (1986)

The Terrorizers (1986)

Dir. Edward Yang

The lives of disaffected urbanites intersect in Taipei through a series of serendipitous encounters. A listless photographer, a struggling novelist, and a mixed-race hustler become entangled with one another as their individual actions precipitate mishaps and misunderstandings that spiral out from personal milieus and disrupt the equilibrium of the everyday. Yang is best known in the West for his three-hour epic Yi Yi (2000), but this early work demonstrates his mastery of the cinematic craft, with a moody, elliptical narrative that offers something new to appreciate with every viewing.

Red Rose White Rose (1994)

Dir. Stanley Kwan

Adapted from a novella by literary titan Eileen Chang, this artful drama from Stanley Kwan is centered on protagonist Tong Zhenbao’s formative relationships with two women in the cultural heyday of Republican China (1911–49). Beautifully shot by Christopher Doyle, a longtime collaborator of Hong Kong auteur Wong Kar-wai, Red Rose White Rose explores the clash between desire and domesticity, modernity and tradition, while constructing a sensual vision of China during a period of rapid social transformation.

Eat Drink Man Woman (1994)

Eat Drink Man Woman (1994)

Dir. Ang Lee

The three sisters of the Chu family live with their widower father in 1990s Taipei. Retired from a glorious career in the high-end restaurant business, the phlegmatic patriarch Old Chu still dominates his sprawling domestic space—especially the kitchen—and whips up lavish family dinners that his daughters have come to view as nothing more than a weekly chore. As dramas and intrigues spill over from the daughters’ individual lives to the kitchen table, Ang Lee and his co-writers, James Schamus and Hui-Ling Wang, train their eye on modern urbanites’ relationships to sex, romance, family, and, of course, food.

Happy Together (1997)

Happy Together (1997)

Dir. Wong Kar-wai

An achingly stylish portrait of a doomed romance, Wong’s feature follows a gay couple from Hong Kong, played by the inimitable Tony Leung Chiu-wai and the late pop icon Leslie Cheung, over the course of a turbulent holiday in Argentina. Dreaming of visiting Iguazu, the waterfall at the end of the world, Leung’s Lai Yiu-fai toils away at a nightclub and restaurant while Cheung’s Ho Po-wing lives a life of dissipation. The two break up and get back together time and again, the rhythms of their ill-fated attraction and sentimental strife in step with a poignant soundtrack filled with the likes of Astor Piazzolla and Caetano Veloso.

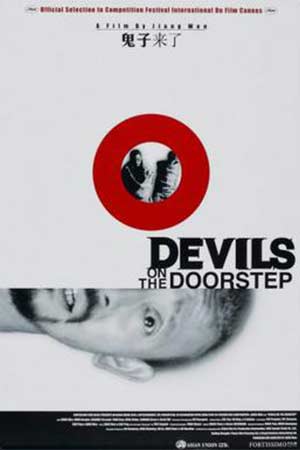

Devils on the Doorstep (2000)

Devils on the Doorstep (2000)

Dir. Jiang Wen

Chinese actor Jiang Wen offers an intensely gripping black comedy about a village under Japanese occupation during World War II, based on the novel Survival, by You Fengwei. Villager Ma Dasan, played by the director himself, is charged with watching over a Japanese prisoner and a bungling translator when an unseen man delivers them to his home one evening. Shot in sumptuous black-and-white, the narrative unfolds as a comedy of errors even while incredible violence thrums below the texture of the prosaic. Nuanced performances and fantastically taut plotting keep the viewer on edge as the absurdity and dark humor build to a horrific climax and unforgettable dénouement.

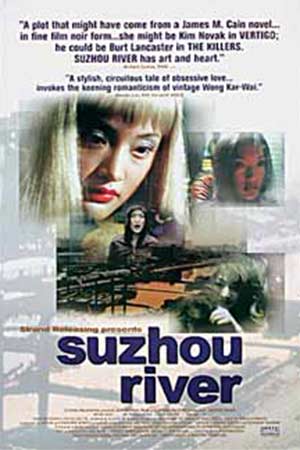

Suzhou River (2000)

Suzhou River (2000)

Dir. Lou Ye

Told from the perspective of an unnamed videographer, Lou Ye’s thriller is an homage to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo and delves into the tale of a motorcycle courier, Mardar (Jia Hongsheng), who falls in love with a young woman, Moudan (Zhou Xun), while living and working near the eponymous river that runs through industrial Shanghai. Years later, after Moudan’s presumed death, Mardar becomes obsessed with her doppelgänger, a nightclub performer who dons a mermaid costume for her show at a seedy tavern. The videographer’s somber narration adds a wistful, uncanny frame to this twisty story that burrows into the underbelly of contemporary China and destabilizes the boundaries of memory and identity.

Editorial note: For more on Hong Kong cinema, see Man-Fung Yip’s city profile in the March 2017 issue of WLT. See also Yingjin Zhang’s “Chinese Cinema in the New Century” (WLT, July 2007, 36–41).