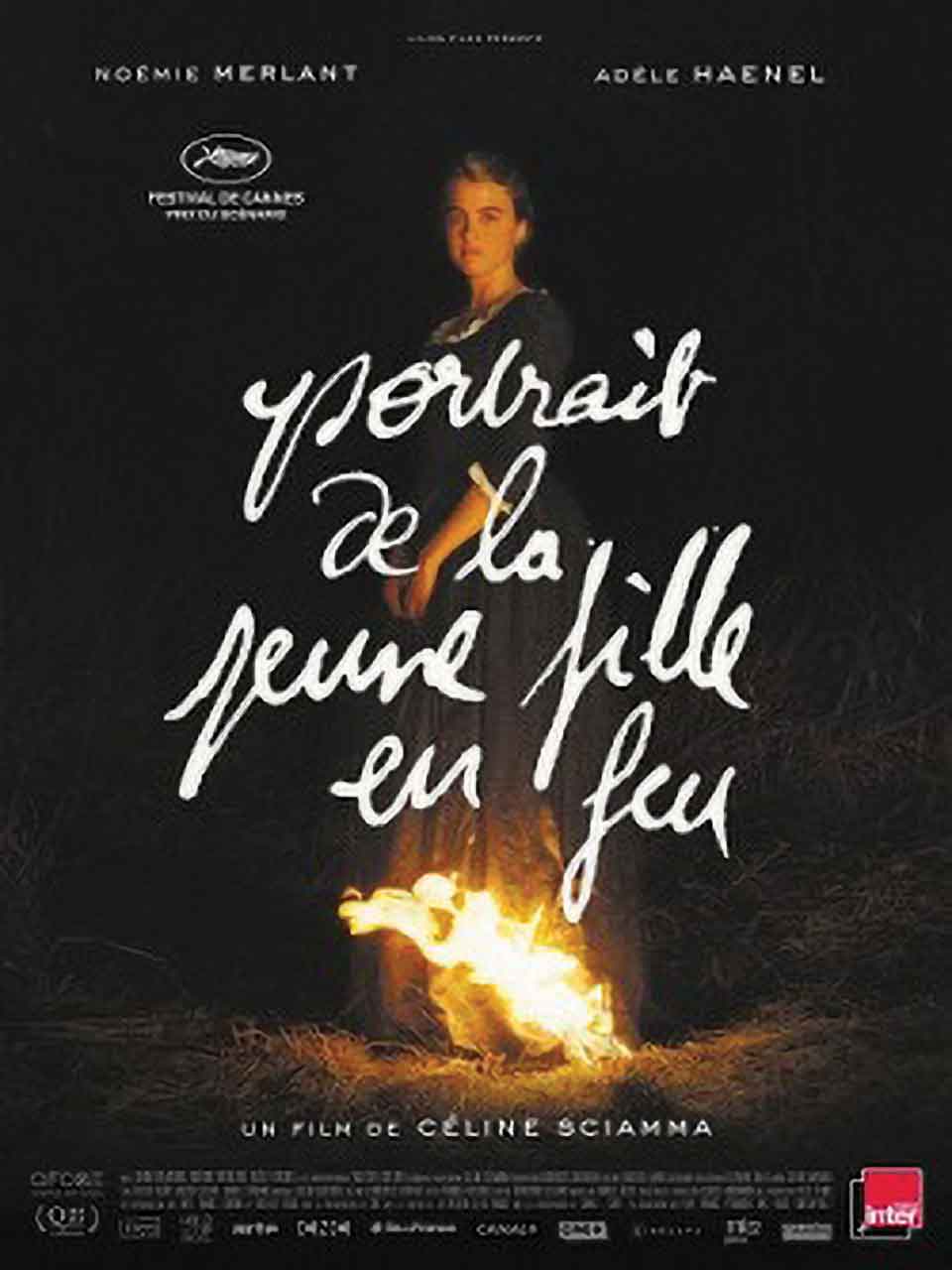

Portrait of a Lady on Fire: A “Manifesto about the Female Gaze”

What to make of the arrival of an LGBT period drama from the time of Louis XV into the twenty-first century? Very much, as Veronica Esposito writes in her consideration of this French historical romantic drama.

Consider the predicament of the young lesbian coming of age in a society that doesn’t know LGBT people exist. This woman would have no language for the attraction she feels; she would have no way to explain her identity to herself; she would have no community to combat the overpowering feelings of confusion, isolation, and estrangement inherent to such a situation. She would feel fundamentally unresolved and out of place, as though she were a discordant note amid a well-tended classical symphony.

And now imagine that she meets another woman, and this lady makes her begin to suspect that she is not alone. This other person opens up the possibility that her identity might be expressible to another human being. She might validate her on the deepest and most intimate levels. And—she is so very overpoweringly desirable.

Except, this woman’s job is to secretly paint a portrait of her so that she can be shipped off to Milan and married to a man.

That, essentially, is the predicament that Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019, dir. Céline Sciamma) elegantly lays out in its first third. It is the late eighteenth century, and the artist Marianne is rowed across turbulent waters to be left on a rugged, windswept French island off the coast of Brittany, where she encounters the innocent Héloïse. Marianne has been brought all this way to surreptitiously forge Héloïse’s portrait.

That, essentially, is the predicament that Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019, dir. Céline Sciamma) elegantly lays out in its first third. It is the late eighteenth century, and the artist Marianne is rowed across turbulent waters to be left on a rugged, windswept French island off the coast of Brittany, where she encounters the innocent Héloïse. Marianne has been brought all this way to surreptitiously forge Héloïse’s portrait.

In her lifetime, Héloïse has only managed to make her will known by frustrating the designs that others have for her life. She has steadfastly refused to let any of the other painters preceding Marianne paint her. Prior to that she had made an even larger refusal, turning away from the world for the isolation of a convent. But she was taken from that refuge and called to serve the economic needs of her family when her older sister made the ultimate refusal—preferring suicide to arranged marriage.

It may be that all lovers are inventing something together, but Marianne and Héloïse are inventing more than most.

It may be that all lovers are inventing something together, but Marianne and Héloïse are inventing more than most, for they are two women with no language to describe their attraction. They only have the glances and gazes that linger and flit around each other as they try to find ways of giving expression to what they are feeling. Surely they would know that their desires are profoundly shameful and immoral, and to state these feelings out loud would be a risk unlike any other. Still, they feel compelled to give voice to who they are. They feel compelled to know each other’s body. We watch as they try to hint at their intentions, to make small gestures of vulnerability in order to gauge any microreaction on the part of the other.

In this story of two women who are trying to come out long, long before coming out was a thing, Héloïse is the innocent of the pair. Cloistered on her island, subjected to her mother’s demands, aching for the mere freedom to run outdoors, she communicates nymphish curiosity and timidity as she casts her eyes down and asks Marianne her many questions. By comparison, Marianne is much the veteran: she has lain with men, and she has committed the great transgression of being a woman who has painted a man’s naked anatomy. In all her womanly reserve and with her powerful artist’s eye, she represents a far more mysterious and sophisticated presence. Yet she too seems lost in the world of her attraction, overcome and subdued by the feelings that are circulating within her.

At times, these women seem to be trying to prove to themselves that their feelings actually exist—that they are real and valid parts of the human experience. At one point Marianne reveals to Héloïse that she was once pregnant, and Héloïse seems taken aback to realize that her would-be lover knows how it feels to be in love. She dearly wants to ask Marianne to explain what love feels like, for she wants to know if what she feels for Marianne is love. It is this combination of innocence, passion, and the desire to articulate the inarticulable that Portrait of a Lady on Fire masterfully orchestrates, slowly building things up—until at last, at a haunting bonfire celebration, everything changes.

But what, really, does change? Yes, Marianne and Héloïse get to express themselves, they get to know the pleasure of each other’s bodies, but they will never be partners living together in a real relationship. Such a thing is not possible in their time, for society has no place for women like them. Accordingly, these women never evidence even the smallest idea of what life would be like if they were free to remain together. The circumstances of the world in which they live would prevent their imaginations from conceiving of such an impossible thing. And yet these are two creative, resilient women: they make use of anything they can to scrape out some space of their own. They comprehend themselves through the myth of Eurydice and Orpheus, the lovers whom fate tears apart and for whom a mere glance is fatal.

Marianne and Héloïse comprehend themselves through the myth of Eurydice and Orpheus.

The end of their affair is foreordained: Marianne will paint the portrait, Héloïse will be married off to Milan. Even more: Marrianne is the only one who could paint Héloïse’s portrait, for precisely what lets her succeed where others have failed is the feminine—and queer—trust that the two feel in each other’s presence. It is this that lets Marianna gaze at Héloïse as no other painter has ever gazed at her before. And this supple gaze is appropriated in order to serve the needs of a proper, heterosexual marriage.

What to make of the arrival of an LGBT period drama from the time of Louis XV into the twenty-first century? Very much, I would say. Filmmaker Céline Sciamma has spoken about how she chose to shoot her movie in ultra-high-definition 8K digital, choosing it over 35mm film in order to give her work a contemporary vividness. To her, this story is still very fresh and relevant, and she wanted the visual texture of the film to reflect this fact.

I would agree with her. Although things have changed a great deal from the era of Marianne and Héloïse, we still do live in a world that makes women the subjected sex, while preventing them from pursuing true freedom. Even more so if they happen to be queer women. A big part of this is the economy of visibility and bodies: we are still perilously close to 1972, when John Berger made the point that “men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” He went on to argue that the fact of the male gaze colonized women’s minds: “The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object—and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.”

We are still perilously close to 1972, when John Berger made the point that “men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.”

Perhaps in response to Berger’s famous statement, Sciamma has called Portrait of a Lady on Fire “a manifesto about the female gaze.” She expanded on this point, stating that her film was “such a strong opportunity to make new stuff, new images, new narratives.” It is these new images, these new forms of gazing that make Portrait of a Lady on Fire feel important and that give it its cinematic power. In the many scenes where we see Marianne gaze at Héloïse, in the extended shots where we see her lay down her brushstrokes and sketchmarks, in the moments when we see Héloïse gaze back at Marianne—here the work of pushing the male gaze to the side is undertaken as two women begin to comprehend how to see themselves and each other.

This tension is felt in a late scene as Marianne paints Héloïse. Now they are truly lovers, and as Marianne works on Héloïse’s official portrait, the latter is unable to suppress a satisfied lover’s smile. Marianne chides her to stop, as the patriarchal world in which her portrait will hang does not want a painting of a beckoning, smiling woman but rather that of a stern, inexpressive one. Still later, after they have made love, Héloïse sees Marianne painting a small portrait of her, and she marvels, “you can reproduce the image to infinity.” With her lover’s eye, Marianne has memorized Héloïse’s image and presence, forging a mental vision that transcends any material rendition. Lacking Marianne’s artistic talents, Héloïse requests that Marianne make a self-portrait that she may have to remember her by, and the latter does so by secreting one into the pages of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, at the conclusion of the tale of Eurydice and Orpheus.

It is such that two women without a language and without any space for themselves co-create the things they need to exist in a world that doesn’t want them. They do so in the margins and from within the pockets of freedom that life serendipitously grants them—much in the way that too many LGBT individuals still must do so in today’s barely tolerant societies. Portrait of a Lady on Fire is a brilliant movie filled with exquisite details throughout, as well as one with a powerful and delightful cinematic eye for gorgeous, meaningful shots and tableaux. The lead performances by Noémie Merlant (Marianne) and Adèle Haenel (Héloïse) are absolute tours de force of acting, as the women evidence an almost preternatural ability to control their faces and gestures and to work off each other’s energy in discovering a panoply of emotions from fear and mistrust to timidity, hesitancy, tenderness, and love. It is a true instant classic, a cinematic pillar that we will be returning to and learning from for some time to come.

Oakland, California