The Cypress Tree

Author’s note: Over the last two decades, whenever I have returned to Palestine, there has been considerable change. However, what I take comfort in is not the changes but the consistencies that have been kept the same and then taught through the family from grandmother to mother to daughter, etc.

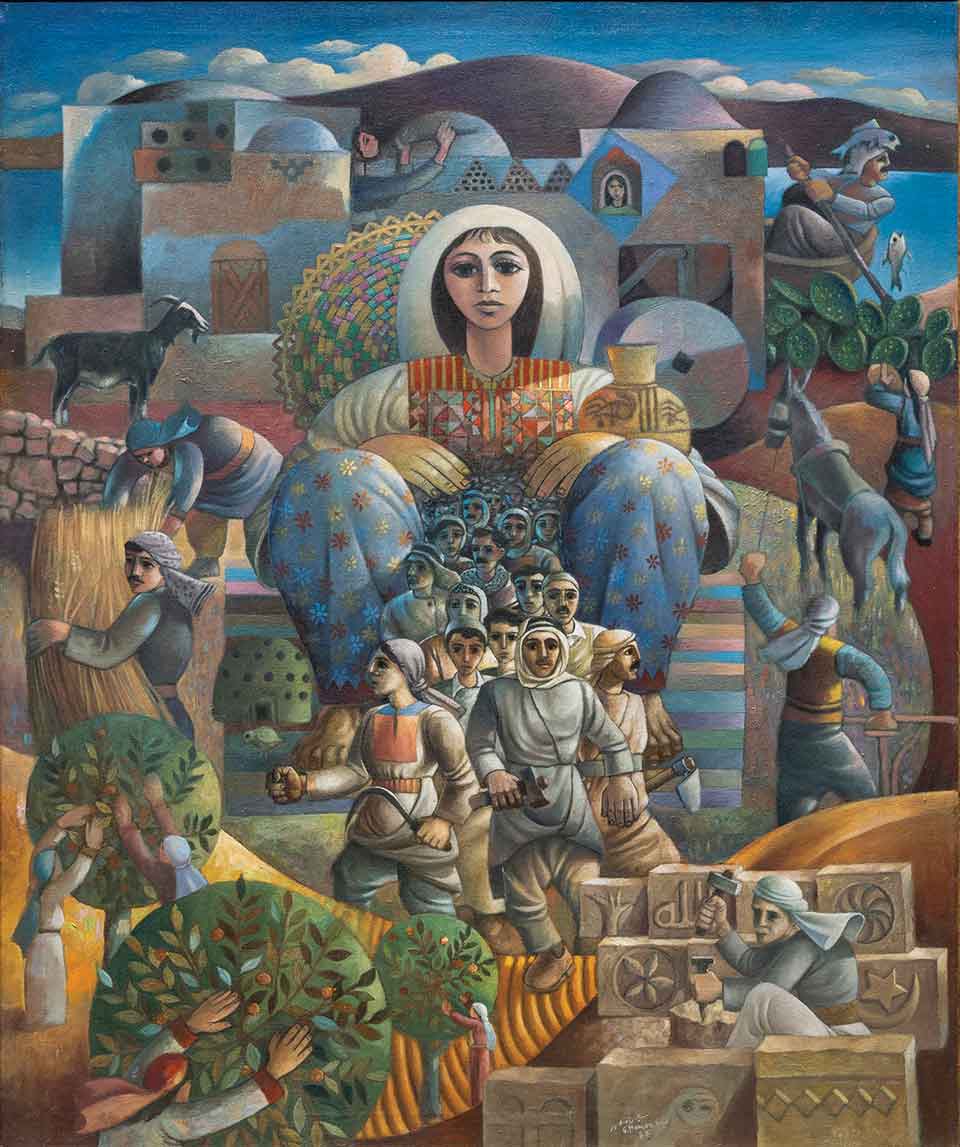

I think of the enduring traditions that have kept the Palestinian people connected to the land and the importance of passing on these rituals. The cypress tree is a symbol on the traditionally embroidered Palestinian dress. It is also a common feature of the Palestinian landscape and has been used as a representation of rural Palestine and as a motif for national poets such as Mahmoud Darwish. “The Cypress Tree” is a female-centric story of the importance of these traditions and how their continuation provides a hopeful framework for keeping our home and memories alive.

My Tata told me about a treasure that is found in a cypress tree garden. I have searched my whole life for this treasure. When I was a child, I lived back in a northern town of Palestine. It is a town that exists on the edges of the West Bank, high up in the mountain ranges, almost touching the peaks of the heavens.

As a child, I used to sit under the cypress tree. It shaded me from the searing midday sun as I searched for the treasure I imagined underneath its soil. As the sun began to drop in the sky, I would leave my treasure hunt behind and skip home to the smell of my Tata’s maklouba; cooked chicken on top of rice, mixed with cauliflower and blanched almonds, as it drifted along the breeze.

When I arrived home, my family was always gathered on the courtyard under grapes, hanging abundantly from the vines. The hot dishes were brought out on brass platters, and just as they were placed down on our table, family and friends would come over and eat with us. I unstacked chairs and we ate and laughed. Dinner would last until the call to prayer echoed out from the minarets. As the guests left the courtyard, I used to go and help my Tata clear away plates in the small kitchen in the back of our home. Afterward, we would sit together and stitch our thawb (thobe) as the light faded in the garden of cypress trees.

Years passed until it was my wedding day. I remember it, as clearly as the sun. The whole town came. The cars lined up on the roads and pressed their horns in rhythmic jubilation. The men erupted into songs of families becoming one. They sang the tune of young love and the promise of children. Our cypress tree held our wedding lights. The fairy-lights in the branches glittered like Christmas in Bethlehem. The starlight twinkled even brighter above them. Even the trees pointed up toward the heavens, reminding us that this was the closet place to heaven on earth, where the soil itself was blessed. The whispers and prayers of our dreams floated in the air. The land was ours, and it was the same garden where my grandmother was wed fifty years before. I wore her thawb. It was embroidered with trees.

I remember how I danced. I danced in the glow of hope. I was going to travel the world and find its treasure.

After we left Palestine, I traveled throughout the earth. I traveled to the deep green countryside and gardens in Tuscany. I traversed the Italian fields and the cities in all their splendor. I sailed down the canals of Venice and stopped in the rolling hills to find the treasure my Tata had told me about. I flitted like a bird across the forests and countrysides of Europe hoping to find it. I ventured to the sprawling palatial gardens of Istanbul. I sought out the dense forests of North America. I searched under the vast rainforest gardens of Asia. I ventured to the gardens of ancient Egypt, but no matter where I went or how much I followed the gardens of cypress trees, I didn’t find the treasure.

Now, I am a mother. I save my money in a jar made of wood. I save it so I can take my children to see our gardens back home. I tell my children the story of the treasure to be found in a cypress tree garden. I hush my children to sleep with stories of a world that at the moment we cannot get to. But in the dead of night, I make plans. I am sure my treasure is back home.

Seasons pass. My children get strong enough to return. The flight is long. My children cannot sit still. They are eager to return to the land of my dreams, but I am apprehensive of what they will find.

We pass through and enter the other side. We travel to the mountain town, my childhood home. As I drive along the route cut from the ancient mountains, I see a familiar sight on the horizon. They are the points of the cypress trees in the fields of my home. We get closer. The streets have fallen into disrepair. The façades of the houses are worn with age, but behind them, my family is still there. The families I grew up with have changed. Their sons and daughters have become owners of the houses. The streets are filled with more children whose faces remind me of their parents. My children join them. They laugh, they play.

My cypress tree garden is empty except for us. There are no weddings in the pale, winter sun. My children hug my cypress tree, take its cones from their branches, and drop them in the soil as they skip home. I search amongst the gardens, but still I do not find my treasure.

I make maklouba in the kitchen, my daughter by my side. We turn out the dish, upside down onto the brass platters, and it is perfectly formed. The steaming rice and chicken is carried to the courtyard where neighbors visit us from surrounding houses, so we pull out more chairs. We sit under the bare grapevines and tell stories of what’s past. How the world has changed. How the world is still the same. The call to prayer fills the skies and the worshippers walk to the blue-dome mosque. My daughter helps me in the kitchen. The small window frames the cypress tree. We stitch her dress full of trees as I tell her about the treasure in the gardens where the light is dying.

Years pass.

Now, I see my cypress tree garden from the window of my daughter’s house. Her children run around the bed I live in. The bed that was once my mother’s and hers. I dream of the treasure under the cypress tree. They brush my hair. My granddaughter is wearing my thawb. She is adorned with trees.

The land around us changes. The scent of my cypress tree blows in from the fields. It smells of gold.

The scent of my cypress tree blows in from the fields. It smells of gold.

I watch as the grandchildren grow. Beautiful. Strong. They study with their schoolbooks. They fall asleep on the end of the bed in the midday sun. They wake up in the night and bring me water when I can’t sleep. I watch as the house fills with visitors. My eldest granddaughter is to be married.

The wedding is in the field of trees. The whole street arrives. The cars line up on the roads and press their horns in rhythmic jubilation. The men erupt into songs of families becoming one. They sing the tune of young love and the promise of children.

Our cypress tree holds their wedding lights. The fairy lights in the branches glitter like Christmas in Bethlehem. The starlight twinkles even brighter above them. Even the trees point up toward the heavens, reminding us that this is the closest place to heaven on earth, where the soil itself is blessed. The land is ours. It is where I was wed in the same harvested fields fifty years before. She is wearing my dress full of trees.

I sit under our tree. I am distracted by the smell of food. It is my maklouba dish. It is being prepared in a house that was once mine. Inside it is a small window. The window looks out onto gardens. I close my eyes and float high, high above the cypress tree until I am looking down upon it. At last I find my treasure.