Writing for the Children of Palestine: A Conversation with Mahmoud Shukair

Mahmoud Shukair is not only enlightening the Arab world on Palestine, he is enlightening the world on themselves. —Yousef Khanfar, founder of the Palestine Prize Foundation

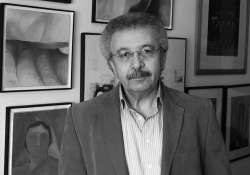

Mahmoud Shukair is a literary giant in Arab and Palestinian literature, with a vast and impressive catalog of literary works spanning over eighty titles, published around the world in twelve different languages. He is the recipient of several awards, including the Mahmoud Darwish Prize for Freedom and Creativity (2011) and the Jerusalem Prize for Culture and Creativity (2015). His 2016 novel Praise for the Women of the Family was nominated for the Arabic Booker Prize.

In my first introduction to him, he is seated on a sofa, with a white curtain hanging over a barred window as the soft twilight of his beloved Jerusalem streams through. He looks sophisticated in a blue shirt and beige jacket. A gold-framed picture of his family hangs on the wall behind him.

He lives in Jabal al-Mukaber, a suburb of Jerusalem, twenty meters away from the house he was born in. I introduce him in this way, because to understand Shukair is to understand his profound connection to Jerusalem, an integral part of his life’s work. Yet his life’s work and the act of writing have had profound, life-changing impacts on his safety and freedom. I seek to discover what makes a literary giant continue to write against all odds and under a brutal occupation.

I believe there are many writers in one man, and after studying Shukair’s body of work, I discerned four stages in his literary life. It was a great honor to discover more about his life, work, and the celebration of his achievements, most recently winning the Palestine Prize for Literature.

* * *

Part 1: Writing for Palestinian Children Living under Occupation

Shereen Malherbe: Mahmoud Shukair, congratulations on becoming a Palestine Prize Foundation laureate. The Palestine Prize Foundation’s role is “to preserve, protect, and promote the Palestinian dreams and achievements.”

Mahmoud Shukair: Thank you, fellow author Shereen Malherbe, and thanks to the Palestine Prize Foundation for honoring me with this award.

Malherbe: As a prolific writer for children, can you tell us how you feel about preserving Palestinians’ dreams for children who grow up in a lifetime under occupation?

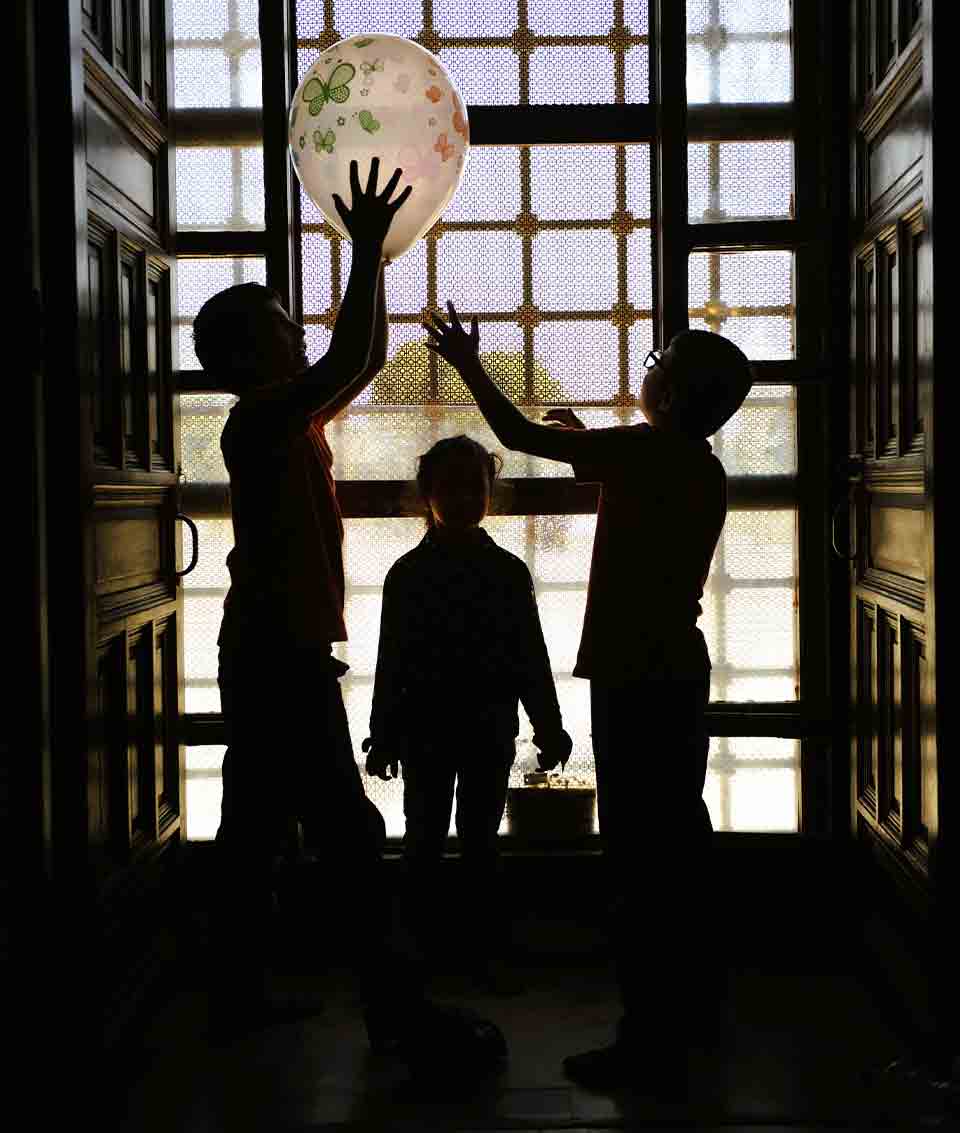

Shukair: Maintaining the dream of Palestinian children born under occupation is never an easy task, particularly when those children are being starved, killed, and subjected to genocide, as is currently the situation in the Gaza Strip. However, I have been keen, in my work writing fiction for children and young adults, to revive the dream of a free homeland in which the children of Palestine enjoy freedom and security. I have always taken care to instill in kids a love of the land, the natural world, and their homeland through concrete, palpable details that they can grasp.

Malherbe: Can you give us some insight into the struggles Palestinian children face? What did you witness?

Shukair: Children in Palestine are experiencing horrific acts of cruelty never seen before on any other child in the world. In Gaza, the starvation of Palestinian children is a deliberate practice that has resulted in a high death toll from malnutrition and insufficient food, particularly milk.

There are children dying due to lack of medication, others killed in bombardments that target civilian homes, and some who remain alive as amputees and orphans after the bombing targets their families.

Due to the genocide that is presently occurring in Gaza, Palestinian children are experiencing trauma, shock, and numerous psychological crises. These kids require medical attention, psychological support, and creative writing that addresses their weary and traumatized souls so they can return to their regular selves.

Malherbe: How does your writing help do this?

Shukair: I try to include an element of enjoyment in all the stories and novels I write for young readers. Even when I write about the brutal practices of the occupation soldiers, I take care to convey it with some calm and without excessive expressions of sadness and grief in order to avoid putting the child in a state of sadness and frustration. I do not encourage placing the child in a state of misery resulting from difficult social and national circumstances, so that he remains optimistic and hopeful for a safe and secure life.

I try to include an element of enjoyment in all the stories and novels I write for young readers.

Malherbe: You were also affected by the occupation throughout your life. Can you tell us more about this?

Shukair: When I write for children, I draw inspiration for my stories and novels from what I see and know of the real suffering of children at the hands of the Israeli occupiers. I also draw inspiration from what I was exposed to by the occupation during my childhood. When I was seven years old, my mother woke me up as the sound of shells and bullets rang in my ears. We had to flee our home that night to find safety away from the gunfire after an armed Zionist gang attacked Jabal al-Mukaber, where my family and I were living. We stayed for four months in the eastern part of our village, then returned home. When I returned home, I felt happy, but the fear of losing my home and stability, which had settled deep within me after that bitter experience, has not left me until now.

Malherbe: We always worry about the children, but what about the impact on you as a writer? Have you suffered from setbacks, frustrations, despair, and so on? If so, how did you handle it?

Shukair: I will admit that because of the challenging political and social environment I live in, there have been moments when I have felt hopeless, frustrated, and like being a writer is pointless. However, I refused to let these negative emotions control me. I collected every ounce of strength needed to push past these emotions. Writing helped with that, along with the culture I had grown up in and shaped for myself.

Malherbe: I read that your stories are based upon true events. Can you tell us more about events that have inspired you to write books?

Shukair: For example, because of fleeing the house, the experience stayed with me for many years, and when I published my first stories in the Jerusalemite magazine al-Ufuq al-Jadeed (New Horizon) in 1962, the story was about that night.

I also wrote a story called “The Soldier and the Toy.” It was based on a real incident that happened to my then-three-year-old daughter, Amina, when she came with her mother to visit me after I was deported from prison to Lebanon. When they returned from Beirut to Amman and on their way to Jerusalem, the Israeli soldier tore up her figurine doll to make sure there were no explosives smuggled inside it.

I also wrote stories for children about real children who were killed by the Israeli army during peaceful demonstrations, including the martyr Ali Afana from Abu Dees, a small town near Jerusalem, and Jamal Al-Zein from Ramallah.

Malherbe: Why was it important for you to write these children’s stories?

Shukair: When I wrote these stories, I was exiled from the city of Jerusalem and from Palestine. When I read about the martyrdom of these two children, I wanted to immortalize them in two stories. I also wanted to convey to Arab children outside of Palestine something about the suffering of Palestinian children who are exposed to various negative practices that reach the point of murder. I published these two stories in an Arab magazine dedicated to children before publishing them in a book that was published in Palestine entitled The Palestinian Boy.

Malherbe: What stylistic elements do you use to convey messages in your stories?

Shukair: I write my stories and novels with a less complex language to mold to the cognitive level of the children’s age group. I am keen to keep the pleasure of reading in what I write. I draw on heritage in quite a few cases to cite figures who have value in Arab culture, such as Saladin al-Ayyubi. I make use of popular songs and Palestinian folktales to make my stories relatable to children. In all cases, I am keen to provide the element of imagination, which is essential for developing children’s abilities and enriching their new knowledge and experiences.

Malherbe: Can you tell us about how you use writing and stories to connect with Palestinian children?

Shukair: Writing is my most important tool for communicating with adults and children, and I am pleased that the children of Palestine deal with my stories and novels with passion and interest. Recently, when I was announced as the winner of the award, a woman delighted me in a comment on social media when she said, “I raise my children on the educational, national, and moral values in your stories.”

I often visit schools and clubs to meet with children to discuss my books, and after Covid-19, I held and continue to hold seminars dedicated to communicating with children in their schools or cultural centers to discuss my books with them.

Malherbe: How important is this for their childhood?

Shukair: I think this is extremely important for childhood, especially with the rise in the popularity of social media. Social media pumps out countless messages, videos, and materials daily that are not appropriate for children. Here, the value of a good book specialized for children comes into play—it takes the child to another realm, introducing them to national and human values.

Perhaps what is important in this regard is that parents, schools, cultural centers, and institutions relevant to childhood should be keen to effect change in several areas: urging children to read, attracting them to take an interest in children’s books, discussing the values, concepts, and behaviors in these books, enabling children to express themselves freely and openly.

Malherbe: Do you have any advice on how we collectively achieve protecting and preserving Palestinian dreams amidst such trauma?

Shukair: I don’t believe in the idea of being superior in teaching children, treating children as if they don’t know anything about what’s going on around them. This is the wrong approach. Children are very smart. All parents, teachers, and educators must do is to have a fruitful, conscious discussion with them in a way that respects their minds, and positive results will come out.

All parents, teachers, and educators must do is to have a fruitful, conscious discussion with children in a way that respects their minds, and positive results will come out.

Great efforts must be made to save children from the current situation in Gaza. Currently there are no schools or kindergartens, and most of the children are homeless and living in tents that do not provide the most basic aspects of a decent life. The voluntary efforts undertaken by some institutions relevant to childhood gain great importance. There are volunteers in displacement areas who gather children to teach them, conduct discussions, and enable children to express themselves and disclose worries. There is some consolation in knowing that children feel warmth in the presence of people who work to understand their needs and enable them to express themselves.

* * *

Part 2: Imprisonment under the Israeli Occupation for Writing

Malherbe: You were imprisoned under the occupation for your representation of the brutality of the Israeli government in your writings. Can you tell us about your experience in prison?

Shukair: I was first imprisoned in 1969. The soldiers came with an Israeli intelligence officer and surrounded the house at night. They knocked on the windows and the door. When I opened the door, they handcuffed me and asked me to stand in the corner of the room. Then they searched the house. They searched the books and found nothing.

They took me to Al-Moskobiya prison, located on the border between East and West Jerusalem. This is where my experience with torture began. After being placed in a cell that was lit day and night for two days, during which I could not sleep, they transferred me to a military prison whose name and location they concealed, and where they practice torture and all forms of oppression against Palestinian detainees. I stayed in that prison, which later became known to Palestinians as Sarafand (located in the center of the country). I spent nine days in a cell that was ninety centimeters long by eighty centimeters wide. I would huddle around myself so I could sleep, without a mattress or a blanket. I was beaten day and night by the investigators because of my political activity against the occupation.

After that, I was returned to Al-Moskobiya detention center, then to Al-Ramleh detention center, then to Al-Damoun detention center near Mount Carmel, where I remained as an administrative detainee. I was released ten months later.

In 1972 I was placed under house arrest for a year. When the October War broke out in 1973, the Israeli occupation force came to arrest me. I was not at home. They left me a letter at home stating that I had to go to the police station, but I did not go. I hid in a house in Ramallah from that moment until it was two weeks after the war, and then I returned home.

In April 1974 I was arrested again and transferred to several Israeli prisons, the last of which was Beit Lid Prison. After ten months of administrative detention, I was deported from prison to the Lebanese border and remained in exile for eighteen years, after which I returned to Jerusalem in April 1993.

The prison experience was bitter by all standards.

Malherbe: Did you have access to books and writing materials? How did you write within these limitations?

Shukair: There is a library in prison, but it has few books and does not satisfy the thirst to read. It was impossible for me to write in the conditions of overcrowding in prison rooms with detainees and the lack of suitable conditions for writing. I am accustomed to isolation and a private atmosphere to write, so I was not able to write any creative text in the prison. I only wrote letters to my family, in which I spoke briefly and did not mention the difficulties inside the prison because the letters were monitored by the prison administration.

I used to read whatever books were available in the prison library, and sometimes I would obsess over some ideas and situations, and dream about stories that I would write when I left prison. I did that when I was deported from prison to Lebanon, where I lived in Beirut for eight months, during which I wrote stories about prison and deportation from the homeland. After that, I moved to Amman and wrote a novel about prison there. However, I decided not to publish it because I did not find it convincing due to its direct political expression and lack of artistic flair.

Malherbe: Can you tell us more about that?

Shukair: I did not write any creative work in prison, but during the second period of detention I was obsessed with writing a novel about the period of imprisonment, the suffering of the detainees, the departure of Gamal Abdel Nasser, and the failure of the coup against the dictator Gaafar Nimeiri in Sudan. When I left prison and was living in exile, I began writing the novel I had mentioned earlier while I was living in Amman in 1976. Its title was Repression. When several friends read the manuscript, they pointed out its overwhelming political directness. I was convinced by their comments and changed the title to “What was said to an emergency visitor.” I toned down the political directness and sent it to the poet Mahmoud Darwish, who was editor in chief of the Palestinian Affairs magazine published in Beirut. Darwish sent me a letter indicating that he would publish the novel in the magazine, then before publishing it, I sent him a letter asking to stop publishing it because I was not convinced and because the political directness dominated the narrative, which directly affected the artistic quality and novel form.

Malherbe: Did your view of Jerusalem alter during this period of your life? If yes, how?

Shukair: This change occurred because of a greater love for Jerusalem, because being away from it is like a child being away from his loving mother. When I was in prison, I remembered my days in the city and became more attached to it, more loving, and more worried about the city from the attempts at Israelization.

While I am away from Jerusalem, I realize that just walking in its streets or sitting in its cafés and restaurants has great value, and we must do this more and not leave any spot in it without visiting and contemplating its details. When I was forced to be at a distance from Jerusalem, it became closer to me. I promised myself that this would turn to utmost attention without wasting a chance to be by the city, closer to it for the remaining days of my life.

I promised myself that this would turn to utmost attention without wasting a chance to be by Jerusalem, closer to it for the remaining days of my life.

Malherbe: What did you dream of achieving once you had your freedom?

Shukair: When I first left prison in 1970, my mind was focused on continuing the political struggle against the occupation. I remember that two weeks after my release from prison, I received a note from the security officer in charge in Jerusalem to go and meet him. I went, and the gist of the interview was to warn me not to do any political work against the occupation or else I would be arrested again.

This warning did not stop me from continuing my political activities, though, and I went on to incite protests against the occupation and its methods of arresting Palestinian citizens: taking their land, destroying their homes, levying high taxes on them, changing the curriculum in their schools, and erasing anything that had to do with their homeland.

When I left prison the second time, not returning home but being forced into exile in Lebanon, I resumed creative writing with energy and activity. I wrote pieces for adults that were published in The Palestinian Boy, my second collection of short stories, and for children that I had published under the editorship of the renowned Syrian short-story writer Zakaria Tamer in the magazine Osama.

* * *

Part 3: Forced Exile from His Beloved Homeland

Malherbe: In 1975 you were deported from Palestine for your political activism. You spent almost two decades in exile. How did exile affect your writing while you were physically distanced from your homeland?

Shukair: My life and writing have been impacted by my banishment from my native country in multiple ways. On one hand, I felt unstable, as if I had severed my roots and was suspended between earth and sky. Throughout my entire exile, I was troubled by my constant yearning for my family, my native Jerusalem, and my homeland.

However, there were advantages to writing while living abroad. In Beirut, I had access to books that were not allowed into the occupied Palestinian territories, and I devoted myself to reading diligently and intently.

Malherbe: What books did exile inspire you to write?

Shukair: I wrote stories for children and about children who were martyred at the hands of the occupation authorities. I wrote the novel mentioned previously, and a story for adults called “Homeland” in which I included my feelings of alienation in the first days following my expulsion. Then came my adult and children’s stories, which were characterized by the specifics of exile, both positively—in terms of being open to Arab and other cultures and being influenced by them to write more mature and substantial literature—and negatively—in terms of alienation, longing, instability, and missing one’s homeland, family, and home.

Exile introduced me to Palestinian writers and intellectuals living in the diaspora and to many Arab writers and intellectuals. Being in exile allowed me to take part in political and cultural seminars and conferences, which improved my life and had a positive impact on my writings, which have been published widely since then.

Malherbe: How did you view Palestine from afar?

Shukair: I was more capable of judging things from a distance, and while in exile, I was able to see the positives and negatives in us Palestinians. I have become able to move away from emotional bias and overenthusiasm, so I see our mistakes and shortcomings objectively and impartially, and at the same time, I can see what is positive in our fighting and in our political programs.

I have become more aware of Palestine’s presence in the world’s consciousness. The misleading Zionist propaganda has been able to distort the image of Palestine as a land without people and a swamp that spreads diseases. This is a lie and a forgery. Individual Palestinians marked by Palestine’s distinct culture and civilization have long existed, and records and images from Haifa, Jaffa, and Jerusalem bear witness to Palestinian civilization and its citizens.

As a result, I began to feel the weight of responsibility placed on my shoulders and on the shoulders of Palestinian writers and intellectuals who are required to defend the truth of Palestine in the face of false and fabricated Zionist propaganda.

Malherbe: What are the key moments during exile that defined you as a writer?

Shukair: I was received warmly in Beirut upon my release from the Israeli prison, not only because I was a political activist but also mainly because I was a writer. I had published a story titled “The Bread of Others” in the Jerusalemite magazine al-Ufuq al-Jadeed (New Horizon) ten years prior to my arrival in Beirut in 1965. The story had been widely circulated and reprinted in newspapers and on radio, particularly during my detention. This increased interest in me as a writer from Palestinian and Lebanese newspapers and magazines in Beirut, which encouraged me to write with passion, responsibility, and interest.

Beirut at that time was busy with daily political activity, including the Palestine Liberation Organization, its magazines, cultural centers, intellectuals, and writers, as well as the parties of the Lebanese National Movement and their various political and cultural activities. All this provided me with incentives to engage in political and cultural activity, which had a positive impact on me.

* * *

Part 4: A Long-Awaited Return to Palestine

Malherbe: In 1993 the Oslo Accords were signed and thirty people were granted the right to return to Palestine. You were one of them. Can you tell us how you felt upon your arrival back to your homeland?

Shukair: I found my return to Palestine, Jerusalem, my house, and my family to be extraordinary by all measures. I never thought I would be back this quickly. When news began to leak about the possibility of the return of thirty deportees who had been deported by the Israeli occupation state from their homeland, I began to follow this news with curiosity to make sure that my name was included on the list of possible returnees. This was, of course, happening during the Oslo secret negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians. I was filled with overwhelming joy when the names of the thirty deportees, who had agreed to return to their homeland, were revealed. I then started to get ready for my return.

We, the returning deportees—well, some of us gathered and the other group stayed for another day—had a happy morning. We were accompanied by our families. We had gathered outside the Palestine Liberation Organization headquarters in Amman, and as the buses headed over the bridge to our homeland, I experienced an unmatched moment in my life. Here I was, returning to Jerusalem after eighteen years away. At the Jericho rest stop, thousands of Palestinian citizens were waiting for us. Members of my family, companions, and friends were there to receive me. I was very happy.

That day, I said to the journalists who had gathered around me to conduct interviews: I am very happy about this return to my homeland, but it is incomplete because large numbers of my people, displaced in the diaspora, are still deprived of returning to our homeland.

Malherbe: Did Palestine change upon your return? What stayed the same?

Shukair: Yes, there were changes on every level. I found Jerusalem surrounded by many settlements separating it from its Palestinian Arab surroundings, and I found Israeli military checkpoints blocking the streets and restricting the movement of people.

I found generations of youth who were born and grew up during my forced absence from the homeland, whom I did not know, including a number of my family members. I found them affected by the First Intifada of 1987, which created generations of fighters who loved their homeland and were prepared to sacrifice for it.

Negatives from earlier eras were also present at the same time. The Intifada had established new values and behaviors free from bigotry and negative views of women. Women took part, were present, and engaged in active struggles. Then the values of solidarity and mutual support faded and were replaced by conservatism, bigotry, restrictions on women’s freedom, partisanship, and destructive, unprincipled competition as a result of the Intifada’s decline and deterioration and the bureaucratic restrictions that the powerful leadership imposed over it.

Malherbe: What stories did you write once you were back home? Were they different from your work in exile? If yes, how?

Shukair: When I returned to the homeland and was able to see the positive developments that had occurred in the course of the national struggle against the occupation, along with the setbacks that accompanied the weakness of the Intifada, I found myself with a clear tendency. I decided to write satirical stories that mock the arrogance of the occupiers and their boasting about the force they impose on a defenseless people, and the erection of barriers that isolate Palestinian cities from one another. I was also motivated to invite well-known figures from around the world to come to the popular Jerusalem neighborhoods to interact with the neighborhood’s residents. I invited the singer Michael Jackson, the Brazilian soccer player Ronaldo, the US secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld, and others.

At the same time, these stories mock some aspects of our society, and in this regard, I have completed writing two satirical short-story collections: The Image of Shakira and My Cousin Condoleezza.

Malherbe: Your later works take on an ironic tone. Can you tell us more about this stylistic choice?

Shukair: These tales mock the occupiers’ conceit and haughtiness while demeaning their status because they flaunt, boast, and display their strength. It makes fun of some of our outdated beliefs, particularly those about women—that they are not as valuable as men and that their freedom should be limited.

To present this mockery in a convincing manner, I used popular proverbs, songs, and narratives drawn from the spirit of the people. I used everything to stimulate the tendency to laughter used by the people.

The art of caricature—which emphasizes certain body parts, like the nose, ears, or eyes, to make an impression on the recipient that is both striking and humorous—was beneficial to me. As a result, some of my characters and their actions came across startlingly and humorously, so the readers enjoy them as they follow the specifics of these stories.

Malherbe: What are you working on now?

Shukair: I am working on narrative texts right now that are more akin to very short stories and are laced with poetic language. They are about the tragedies that the Israeli occupiers are committing, which result in the deaths of tens of thousands of women and children, without any thought of conscience or deterrence.

These texts focus on the human side of the suffering caused by bombardment, starvation, displacement, and genocide. They are narrated by an educated man who lives in Jerusalem and his granddaughter, who lives in Rafah, a city south of the Gaza Strip, and joins in the narration. As a result, the texts read like a novel with sequential scenes and chapters.

Malherbe: What future do you see for your beloved city, Jerusalem?

Shukair: Over the course of its long history, this city—my dear Jerusalem—has been the target of numerous invasions. It was destroyed seventeen times by invaders, but each time it arose from the ashes and life was restored. It is a city dedicated to diversity, the coexistence of different religions and ideas, and the coexistence of people in tranquility, security, solidarity, and peace. Its seven gates open to all sides confirm its nature dedicated to pluralism.

Jerusalem’s seven gates, open to all sides, confirm its nature dedicated to pluralism.

It is currently subject to an exclusive vision imposed by the Israeli occupiers, one that shows Jerusalem as Israel’s permanent capital. No matter how much the occupiers try to alter the true landscape of the city, how much they try to lower the number of Palestinians living there, how much they tax, how many homes they demolish, how many settlement outposts they establish both inside and outside the city walls, or how much they encroach on the city’s holy sites for Christians and Muslims, this closed vision is inconsistent with the nature of the city and will not succeed.

For its Muslim, Christian, and non-Zionist Jewish residents, Jerusalem will continue to be an Arab Palestinian city. It is a wonderful city that inspires hope and harmony in the hearts of people all over the world and is committed to diversity, love, and peace.

Malherbe: How important is the role of the writer in this vision?

Shukair: In the same way that the city instilled in me the values of tolerance and open-mindedness, I have honored these lofty ideals in my stories and novels, championed them, and made them central to both my varied and multifaceted writing style and outlook on life.

Malherbe: What advice do you have for them?

Shukair: Since Jerusalem is a city of pluralism, openness, and peace, I advocate for the need to respect Jerusalem’s inherent qualities. When the occupation authorities try to Israelize the city, make it limited to one narrow vision, and exclude other visions, they are thereby entering into a blatant contradiction with the nature of the city and the essence of its life, and these attempts based on violence and coercion will not succeed.

Malherbe: Thank you, Mahmoud Shukair, for sharing your life’s work and journey with us. It has been an inspirational journey, one that culminates in a lifetime achievement award for the Palestine Prize Foundation to recognize you as its well-deserved 2023 literature laureate.

July 2024

Translation from the Arabic by Alice Yousef

Editorial note: Shukair’s story “The Little King” appeared in the “Palestine Voices” issue of WLT (Summer 2021). Malherbe’s story “The Cypress Tree” also appeared in the issue. For more information about the Palestine Prize Foundation, visit www.palestineprize.foundation