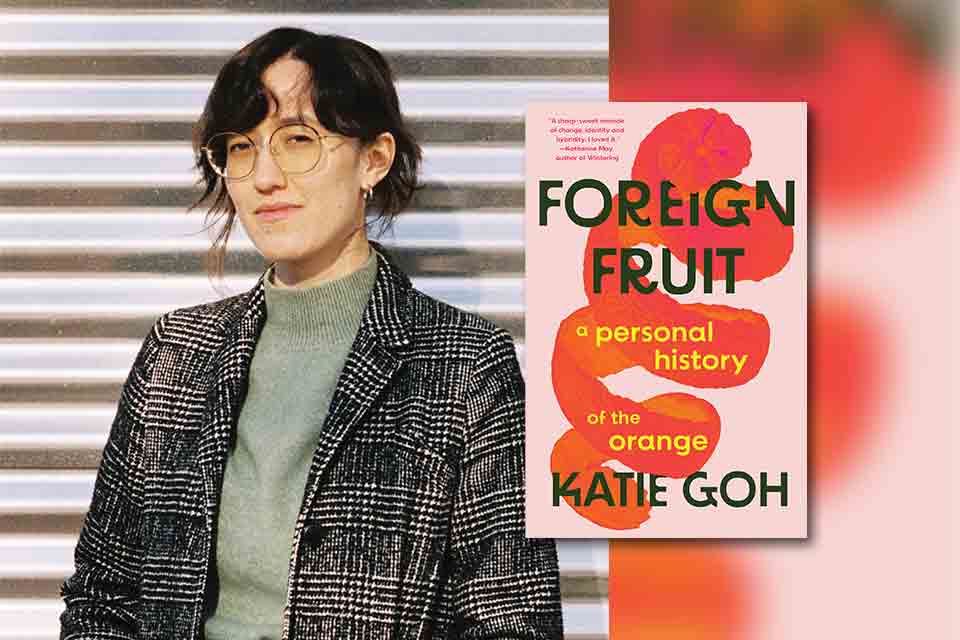

9 Questions for Katie Goh

In May, Katie Goh’s Foreign Fruit: A Personal History of the Orange was published by Tin House. A hybrid work of memoir, science, and history, Foreign Fruit follows the complicated history of the orange, an investigation that parallels Goh’s search into her own heritage.

Q

In Foreign Fruit, the history of the orange as a narrative frame for your own heritage seems to shift as we move through the book. It’s less straight line, more kaleidoscope. Reading is an engaging experience of watching you follow the metaphor in perhaps unexpected directions. Did the metaphor’s malleability surprise you as you wrote?

A

It really did surprise me. When I started researching its history, I was amazed by the journey this very humble, very everyday fruit has been on, from China, across the Silk Roads, to Europe and beyond. This geographical and chronological journey seemed straightforward enough, but when I began to dig deeper, it became more muddy, more complex and uncertain. We think the orange began life near the Tibetan Plateau, but this origin is contested and there’s no one perfect creation myth.

This uncertainty of the orange’s origins was an appealing metaphor for me writing about my heritage. There’s also the hybridity of the fruit—the orange is a hybrid of other citrus fruit—which was a perfect metaphor for writing about my mixed-race identity. And then the orange’s meaning has changed throughout history, with different religions and cultures finding their own metaphors in the fruit. That was a perfect entry point for me to explore bigger issues like globalization, colonialism, and ecology—all of which is tied into ideas of heritage and identity too.

Q

I enjoyed learning the history of the orange, which you’ve carefully researched. Really, I was hooked by the prologue’s abundance of facts. What was one of your favorite discoveries about oranges?

A

I think my most shocking discovery was how the orange—and other citrus—was so integral to the European expansion and colonial mission, as it was used for medicinal purposes to combat scurvy. Citrus groves were planted along common ship routes so sailors could top up their vitamin C level. Orange saplings arrived on the First Fleet to Australia, and Christopher Columbus brought seeds to America on his second voyage to the “New World.” Some historians think that European expansion would have been much more improbable without citrus, and it’s incredible that this small fruit was used as a tool for violent empire and shaped our modern world.

It’s incredible that this small fruit was used as a tool for violent empire and shaped our modern world.

Q

What books are you most excited about in 2025?

A

Tash Aw is releasing a new novel, The South, which is the first of an epic four-book series about modern Malaysia—I’m excited to start that soon. I really enjoyed Katie Kitamura’s Intimacies, so I’m looking forward to her new novel, Audition. And on the nonfiction front, I can’t wait for Robert Macfarlane’s Is a River Alive? and an English translation of Annie Ernaux’s The Other Girl.

Q

You frequently write about film, literature, and music, with, for instance, articles on how the films Minari and First Cow are rewriting the American Dream, how Asian food Instagrams joyously resist racism, and how sex and subservience disrupt clichés in 2020’s most terrifying horror movies. What in culture currently has your keenest attention?

A

I’ve been catching up with the awards-nominated films recently, and it seems like the myth of the nation is coming up again and again. Culture interrogating the idea of nationhood is hardly a new concept, and in this current moment—when countries are operating as businesses acquiring new borders like mergers—it feels like we’re scrambling to try and figure out what makes a nation a nation and a people a people. Anora, The Brutalist, The Apprentice, even Wicked are all playing with the myths of America, democracy, and freedom, and I’m intrigued to see if and how filmmakers keep developing these ideas during another Trump presidency.

Q

Is there something from culture—an album, a movement, a TV show, anything—that you think has best captured the zeitgeist of the 2020s so far?

A

Like everyone, I love the television show Severance. Yes, it’s about work and labor, but I think the outie/innie metaphor extends beyond our day jobs: it’s the creation of online personas, it’s our inability to truly know anyone (including ourselves), it’s the desire for ignorance over knowledge. It’s all unbearably contemporary.

Q

Book reviews are a substantial part of every issue of World Literature Today. You’ve written many book reviews, and I’m wondering: What would you say makes a good review?

A

Honestly, enthusiasm. Whether the reviewer did or didn’t like the book, I want to be persuaded by someone’s argument. I think good criticism is criticism you enjoy reading, even if you don’t agree with the reviewer’s judgment.

I think good criticism is criticism you enjoy reading, even if you don’t agree with the reviewer’s judgment.

Q

If you could put one book in everyone’s hands, what would it be and why?

A

Wolf Hall changed my life when I was a teenager. I had no idea historical fiction could be written like that: specific, intimate, humane. Wolf Hall is a novel, but it also changed how I viewed history: fact turned into human hubris, history made modern, the dead brought back to life.

Q

What do the best stories do?

A

They offer their readers a new perspective on the world. Whether it’s a story in book form, a movie, a game, or one told across a pub table, the best stories recalibrate your perspective, so that when the story is finished and you step outside again, the world seems a little different than before.

Q

Where are your favorite places in Edinburgh?

A

I am very lucky to live in a city with a thriving independent bookshop scene. There’s The Portobello Bookshop by the sea, the politically radical Lighthouse in the Old Town, and Golden Hare Books in the New Town, just to name a few. Writers flock to Edinburgh, in large part for the community of book lovers in the city. The National Library of Scotland also has a very special place in my heart: it’s where I write best, from struggling over university essays when I was a student to finishing the final draft of Foreign Fruit.

Katie Goh is a writer, editor, and author from the north of Ireland, currently living in Edinburgh.