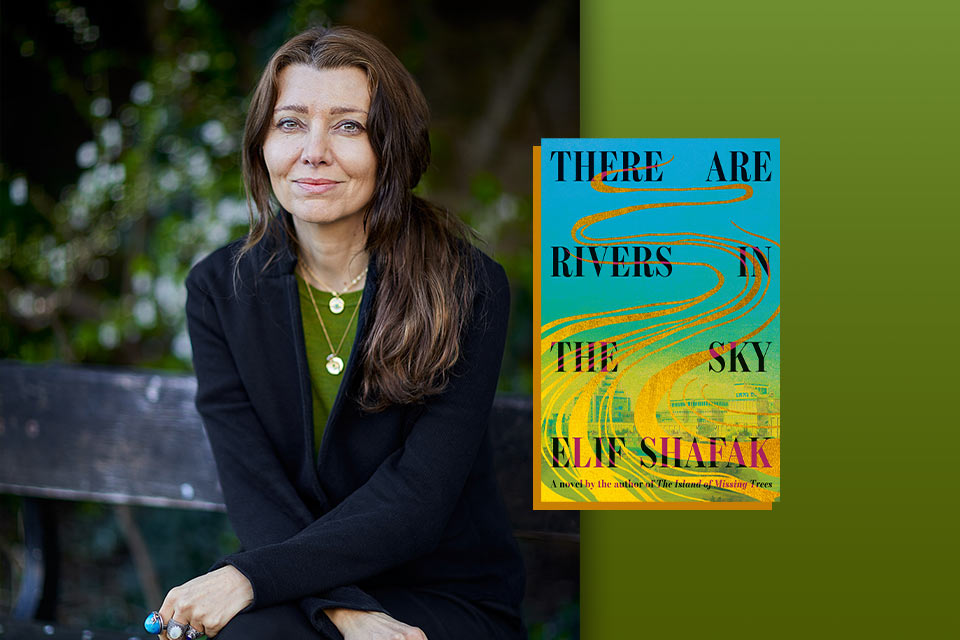

9 Questions for Elif Shafak

In August, Knopf published Elif Shafak’s new novel, There Are Rivers in the Sky. In this story spanning centuries, three characters are connected by history, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and water: Arthur, living in a Dickensian nineteenth-century London while translating cuneiform tablets; Narin, whose Yazidi family is being pushed out of their home in twenty-first-century Turkey; and Zaleekhah, a hydrologist in twenty-first-century London who is working to restore lost rivers. The past and present repeatedly overlap and then ultimately merge in an astonishing ending.

Q

When the novel opens, we get a peek into King Ashurbanipal’s library. He will someday be remembered as “The Librarian King” and “The Educated Monarch,” yet he is brutally cruel. The cruel headmaster in Arthur’s school, too, is surrounded by books. Some people believe that reading develops empathy, but that isn’t so with either of these men. What is your view of the relationship between reading and empathy?

A

I do believe that reading, especially reading fiction, develops empathy, connectivity, and understanding. I know this because it happened to me. Books have changed me profoundly. Ever since my childhood, they have shown me the possibility of other worlds, other existences, connecting me with lives beyond my tiny little corner of the universe. However, it is also true that education alone does not automatically make one wiser or kinder. My grandmother, the woman who raised me until I was ten years old, was not a well-educated woman, only because she had been pulled out of school in Turkey at a young age; just for being a girl she had been denied a proper education. Yet she wholeheartedly believed in women’s independence. Grandma was one of the wisest people I have ever met throughout my life. She showed me how there are multiple paths to knowledge and wisdom, and inside oral culture, there are wells of wisdom that need to be studied and appreciated.

Ever since my childhood, books have shown me the possibility of other worlds, other existences, connecting me with lives beyond my tiny little corner of the universe.

Q

The controversial Ilısu Dam project, in Turkey, figures prominently in the story, which is closely connected to rivers and water in its various forms. The Epic of Gilgamesh, also at the center of the novel, includes a great flood. Do our oldest stories inform our current crises?

A

The Ilısu Dam has catastrophic consequences for the environment. The dam has a lifespan of only fifty years, and yet, in order to build it, thousands of years of historical heritage and valuable natural habitat have all been destroyed, hundreds of thousands of people have been displaced. Today the area is inundated, history gone. All around the world, when we talk about climate crisis, we are mainly talking about water crisis. This affects the lives of women and minorities in a very deep way. Women are water-carriers, just like they are memory-bearers. When rivers dry up downstream, for instance, and there is no water for entire communities, women have to walk longer distances, increasing the danger of gender violence.

Women are water-carriers, just like they are memory-bearers.

We have to connect all these dots. If we care about environmental crisis we care about gender inequality; if we care about gender inequality we care about racial and regional inequalities; and so on. They are all inseparably connected. The land where I come from experiences the lack of water acutely. Out of the ten most water stressed nations in the world, seven are in the Middle East and North Africa. The Epic of Gilgamesh, told and written thousands of years ago, is deeply relevant to our world. The old story has a lot to tell us, if we care to listen. It does tell about crisis and loss and destruction but also about resilience, hope, renewal.

Q

In The Buried Book, David Damrosch describes The Epic of Gilgamesh as “the first great masterpiece of world literature.” How do you define “world literature”? What are a few of your favorite examples?

A

I so agree with Professor Damrosch. The Epic of Gilgamesh is the earliest universal story with an enduring impact that transcends borders of time and place. That is what great works of literature do—they transcend and transform. Don Quixote de la Mancha, for instance. The Iliad and the Odyssey by Homer. Dante’s The Divine Comedy. In Search of Lost Time, by Proust . . . and so many others have that same universal and timeless core.

Q

Arthur has lexical-gustatory synesthesia: he tastes words. I’d heard of the form of synesthesia where people associate colors with letters, but LG synesthesia was new to me. How did it find its way into your work?

A

I have a very mild form of synesthesia, something that took me years to understand. I have always been puzzled by the taste of words on my tongue. Not only in my native language, Turkish, but also in Spanish and English, both of which are, for me, acquired languages. Does our perception of words change as we move from one language to another? Are we slightly different people in different languages? All these questions intrigue me immensely, not only as an intellectual subject but also for purely personal and emotional reasons of belonging and nonbelonging.

Q

I was stunned when I read in a Guardian article that you listen to heavy metal music while writing (I work in silence). Which bands are on your writing playlist, and why do you suppose heavy metal provides the best writing backdrop for you?

A

I cannot write in silence, I get panic attacks. In a very tidy, pristine, and completely silent room, I can’t even think properly. I love the sounds of the city, the sounds of nature. And I love music. I put on my headphones and listen to the same song seventy or eighty times, over and again. I enter into a loop of energy, which helps me focus better on my writing. Since my early youth I have been a metalhead. I love multiple subgenres of heavy metal: gothic, progressive metal, melodic death metal, industrial, symphonic, or power metal. . . . I have written many stories listening to System of a Down in the past, for instance. I was heartbroken when they broke up.

I listen to all kinds of bands from all over the world, from the US to Ukraine to Mongolia, but especially I love Scandinavian bands. Just to name a few from my playlist: Lorna Shore, Archenemy, Sleep Token, Amon Amarth, In Flames, Wintersun, Jinjer. . . . Heavy metal has so much energy, fire, passion, and honesty. It is about raw emotions. It can bring contrasts together in remarkable harmony. Some people assume that this music makes one aggressive, but in reality, when you look at heavy metal musicians, many of them are kind, gentle souls.

Q

Book bans are on the rise in the US—particularly in schools and libraries. What can we in the US learn from Turkey about the ascent of censorship?

A

I find the rapid acceleration of book bans and book removals across the US very alarming and important. This not only an attack on writers and poets, not only an attack on libraries and literary spaces, but also an attack on our freedom to connect with knowledge, imagination, empathy, and ultimately, humanity. It has consequences for an entire culture and society. It undermines democracy. In this sense, the US can learn from Turkey.

I wrote a novel, The Bastard of Istanbul, that told the story of a Turkish family and an Armenian American family through the eyes of generations of women. My book focused on the silences buried in history and mentioned the Armenian Genocide. When the novel came out, I was accused of “insulting Turkishness” by the authorities, called a “traitor” by ultranationalists, and put on trial alongside my fictional characters. The prosecutor demanded three years in prison for me. Another time, I have been investigated for the “crime of obscenity” because in one of my novels, 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World (WLT, Winter 2020, 76), I wrote about a sex worker in Istanbul, and in another novel, The Gaze, I wrote about gender violence and child abuse. Police officers have come to my Turkish publishing house and taken my books to yet another prosecutor’s office and so on. I have experienced several times the dangers of authoritarian intervention into literature, libraries, and book spaces.

Knowledge-censorship and empathy-censorship will only deepen the polarization of our societies, the breakdown of democratic norms, and the erosion of coexistence. In a world torn apart by walls of apathy, literature is a bridge-builder.

Q

What cultural offerings or trends have recently captured your attention?

A

I have recently joined Substack, which is, of course well known in the US but not so much on this side of the Atlantic. Today many social media platforms are all about either anger and division or polished/edited/perfect photos, whereas on Substack it is possible to share essays about ideas, literature, the craft of writing, the art of storytelling. My newsletter Unmapped Storylands is free for the most part, and I appreciate the literary community around it, the relationship with both readers and fellow authors.

Q

What have you recently read that you would recommend to our readers?

A

I have read The Vulnerables, by Sigrid Nunez. It is utterly brilliant, beguiling. I will now start reading 36 Ways of Writing a Vietnamese Poem, by Nam Le. I am intrigued by the way he deals with identity, belonging, roots.

Q

The news can be quite overwhelming, and, as your brilliant novel reminds us, this is nothing new. On the darkest days, what picks you up?

We need to hear each other’s voices in these liquid times.

A

We all feel anxious, depressed, angry, frustrated . . . an almost existential fatigue. This is the Age of Angst, but if we were to tumble into the Age of Apathy, I think it’d be a much darker world. We need to hear each other’s voices in these liquid times. I think global solidarity is so important, as is global sisterhood. We need to connect with three things: with our fellow human beings, with ourselves (the inner garden), and with the environment and ecosystem. Seemingly small things can make a huge difference. A walk by the river, acts of kindness and compassion, pockets of love. . . .

Elif Shafak is an award-winning British-Turkish novelist and a champion of women’s rights. Her books have been translated into fifty-five languages. Her novels include The Forty Rules of Love; 10 Minutes 38 Seconds in This Strange World, which was a finalist for the 2019 Booker Prize; and, most recently, The Island of Missing Trees.