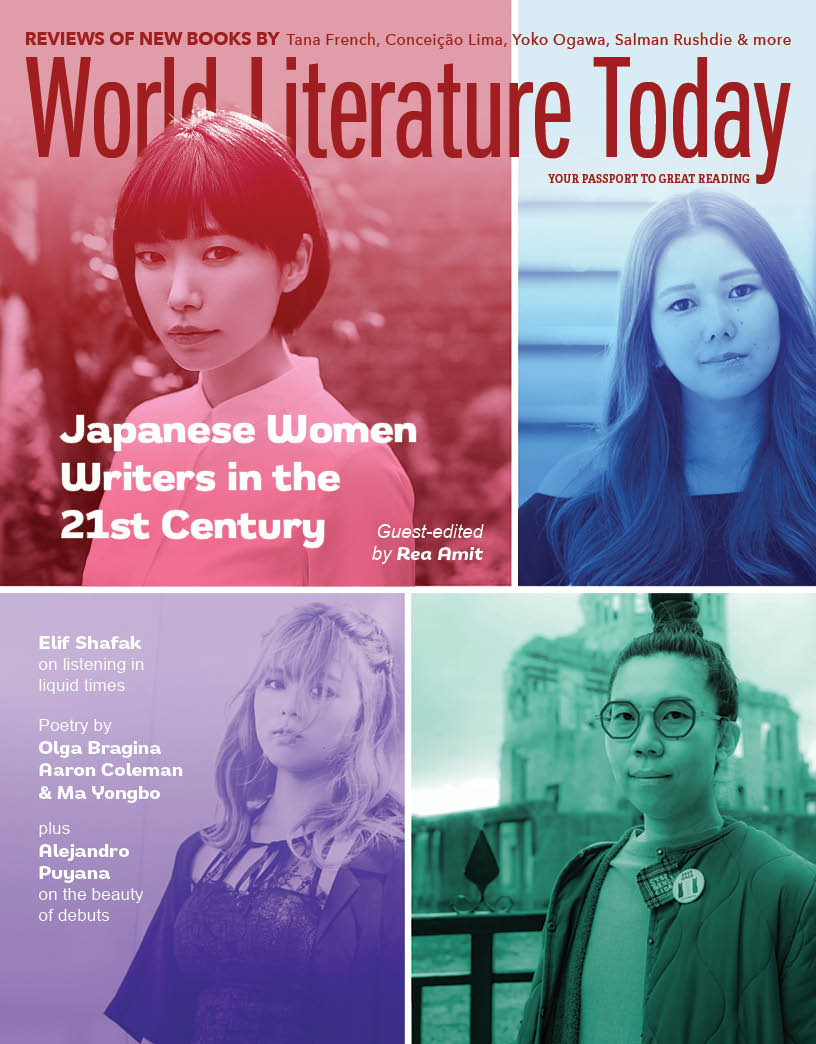

Contemporary Women’s Literature in Japan: A Very Short Introduction

It is an undisputed fact that women played an integral role in the development of modern Japanese literature. As early as the late nineteenth century, Ichiyō Higuchi broke through the literary establishment’s gender barriers to become a writer despite blunt gender discrimination. Japan’s most prestigious literary prize, the Akutagawa Prize, was awarded to a female author for the first time just four years after its initiation in 1935, when Tsuneko Nakazato received the honor. Since then, numerous women writers have also won the award. However, men not only overwhelmingly outnumbered women in receiving the prize, but they also predominantly held the positions of taste arbiters.

It is an undisputed fact that women played an integral role in the development of modern Japanese literature. As early as the late nineteenth century, Ichiyō Higuchi broke through the literary establishment’s gender barriers to become a writer despite blunt gender discrimination. Japan’s most prestigious literary prize, the Akutagawa Prize, was awarded to a female author for the first time just four years after its initiation in 1935, when Tsuneko Nakazato received the honor. Since then, numerous women writers have also won the award. However, men not only overwhelmingly outnumbered women in receiving the prize, but they also predominantly held the positions of taste arbiters.

Moreover, the unofficial Japanese literary guild, the bundan, was primarily a male institution. Women continued to publish on the periphery, enjoying varying degrees of popularity, but throughout most of the twentieth century, they failed to amass enough influence to challenge the male domination over the field. Notable women gaining recognition during the middle of the twentieth century included Fumiko Enchi and Sawako Ariyoshi, while works by Fumiko Hayashi were revived in the postwar era through several film adaptations directed by Mikio Naruse.

To be sure, several women were already advocating for gender equality in the prewar period, with notable figures such as writers Raichō Hiratsuka and Akiko Yosano leading the way. However, it wasn’t until roughly the last decade of the twentieth century, many years after the war, that a first full-fledged wave of women writers emerged in the East Asian nation. Among these writers, Banana Yoshimoto stood out for her apparent disinterest in establishing herself within male literary circles, choosing instead to position herself outside any predetermined establishment. Rather than narrating social mores using overly complex and defamiliarizing language, Yoshimoto often focuses on seemingly minor or less conventional aspects of life, including food, in plain, easy-to-follow stories centering on the everyday.

In contrast, other writers initiated a disruption in Japan’s male-dominated literary institutions, although perhaps not intentionally. Among the most prominent figures during this pivotal moment in the history of modern Japanese fiction were authors such as Yōko Tawada, Yōko Ogawa, Hiromi Kawakami, and Yu Miri. Unlike Yoshimoto’s 1990s seemingly cute (kawaii) fiction, which was closely associated with girls’ culture (shojo), these writers actively demanded attention and compelled readers to reconsider conventional notions of women’s literature.

Such late twentieth-century Japanese women writers emerged with a heightened urgency to depict life from an unabashedly and unapologetically female perspective. For instance, Ogawa’s 1990 Akutagawa award-winning work “Pregnancy Diary” diverges from the typical romantic narratives of pregnancy, offering instead an unflattering and even superfluous portrayal of this innate female experience. Similarly, Tawada displayed a penchant for vulgarity and an unorthodox exploration of sexuality in her 1992 Akutagawa Prize–winning story “The Bridegroom Was a Dog.”

Tawada’s voice as a writer quickly transcended Japan’s borders as she began publishing works directly in German, establishing herself as a unique transnational literary figure. A similar complexity in projecting Japanese identity can be found in Yu Miri’s stories. Although written exclusively in Japanese, these stories reflect the unique experiences of people in Japan who are of Korean descent. In addition to the depiction of transnationality in works by Japanese women authors, the ultimate means of establishing their presence, along with their contemporary counterparts, was the international attention they received beyond their home country through translations into numerous languages, including French, German, Chinese (both Mandarin and Cantonese), and Korean, but especially into English.

* * *

The rise of these early and contemporary women writers can therefore be attributed—at least partially—to a young and talented new generation of translators, including David Boyd. He was a guest at the University of Oklahoma in early April 2024, when he participated in several events focused on contemporary Japanese women writers and translation. A previously unpublished translation by Boyd is featured in this special section.

While women writers of the past often had to wait for a decade or more, after achieving domestic success, before their works gained international attention, their contemporary counterparts didn’t have to endure such lengthy waits. For instance, Hitomi Kanehara won the Akutagawa Prize in 2003 for her sexually disturbing and violent novel Snakes and Earrings, which was translated into English within only a few months of receiving the award. The portrayal of a young, rebellious female character in that work remains as bold today as it was back then. An essay by Allison L. McClung that features a more direct discussion of Kanehara’s novel is also included in this issue of WLT.

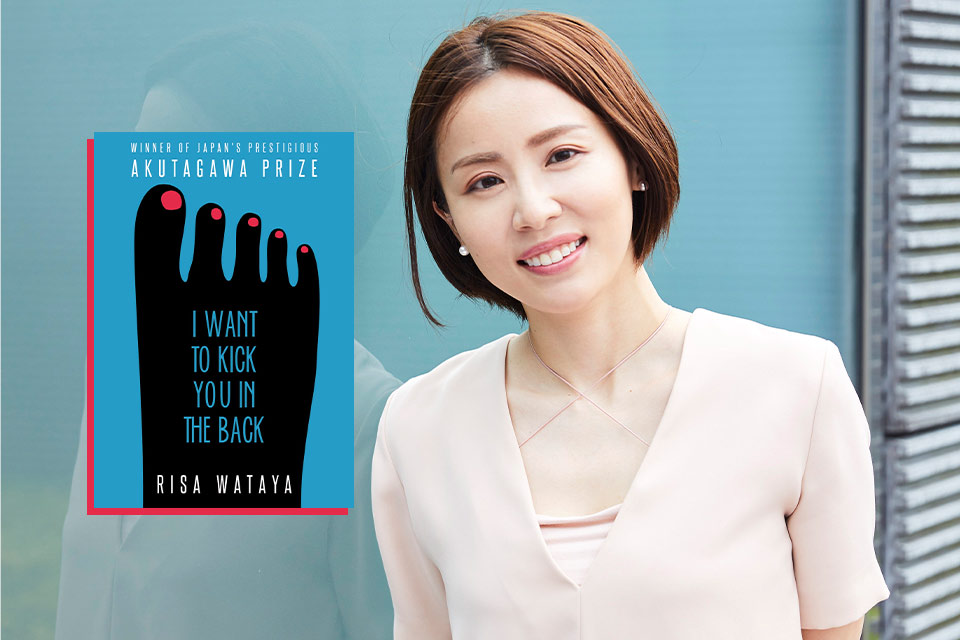

In addition to the audacity that characterizes Kanehara’s work, her recognition was also marked by her age. She was only twenty-one years old when she received her literary accolade. Alongside her in 2003, another young talent, Risa Wataya, also won the highest literary prize with her novel I Want to Kick You in the Back, at the age of only twenty. While the Akutagawa Prize is typically awarded to up-and-coming writers taking their first steps in literature, Kanehara and Wataya can be viewed as a revitalizing force that has injected new female agency into Japanese literature.

Other writers who emerged through this youthful vitality in the literary wave include Nanae Aoyama, who received the prize in 2006. However, arguably the most prominent voice was and remains that of Mieko Kawakami, who won it in 2007. Unlike her predecessors, Mieko Kawakami (not to be confused with important writer Hiromi Kawakami, who won the prize in 1996 and belongs to a previous generation) portrays an uncompromising reality in which women claim power as a matter of fact rather than as an act of rebellion.

Unlike her predecessors, Mieko Kawakami portrays an uncompromising reality in which women claim power as a matter of fact rather than as an act of rebellion.

Notable in this regard is Mieko Kawakami’s masterpiece, Breasts and Eggs, wherein female characters engage in discussions about reproduction and breast implants, while to some degree they disregard gender-based pressures. In this novel, femininity is not reduced solely to physical attributes or women’s bodies in general; rather, it is elevated to the realm of discourse with practical implications. McClung discusses this work in her adjoining essay as well. Another significant example within this context is the prolific writer Hiroko Oyamada, who is featured in a special interview in this section. Oyamada’s female characters, though not overtly so, nonetheless embody a feminist perspective on the world. They achieve this through narratives that, seemingly unintentionally, navigate a delicate balance between reality and fantasy, thereby suggesting a third path between these binary oppositions.

Indeed, as the writer herself expressed in our interview included here, her intention is not to delve into surrealism but rather to illuminate aspects of the human experience that often escape notice. For too long, it can be inferred, this overlooked perspective was the experience of being a woman, not only in Japan but elsewhere as well. The unique female experience, transcending gender binaries, is alluded to in Oyamada’s works such as The Hole (2014, translated by David Boyd), where the female protagonist, following her husband, relocates to a rural town. There, she forges connections not only with her mother-in-law and a mysterious, hidden family member but also with an unidentified animal.

Sayaka Murata also explores the possibility of a female experience detached from traditional sex and gender binaries. In her Akutagawa Prize–winning novel Convenience Store Woman (2016), she portrays a female protagonist who seems uninterested in conforming to societal expectations or pursuing romantic relationships, instead dedicating her life to working at a convenience store. While the depiction in this novel is largely positive, Murata also examines the risk of exploitation and abuse in her second book translated into English, Earthlings (2020, originally published in 2018). In this novel, she portrays a girl’s upbringing as an outsider, sometimes even alien-like, initially as a matter of choice but also as a psychological coping mechanism to suppress extremely painful experiences.

Extreme devotion, which sets a girl apart as an outsider, is also a defining characteristic of the protagonist in Rin Usami’s 2020 Akutagawa Prize–winning work, Idol, Burning. In this story, a teenage girl directs most of her energy and attention toward idolizing a male pop icon. Her devotion is not based on the idol’s appearance or talents but serves as a central activity that shapes her identity. Usami, who was herself of a similar age to her protagonist when she wrote the story, presents a nonbinary perspective to examine contemporary society. This perspective extends beyond orthodox gender roles and also challenges the division between mental health issues and competence.

While the focus of this introduction has leaned toward the recognition of Japanese women writers through literary awards, it’s important to note that their achievements extend beyond these accolades. Many other writers contribute to making this contemporary wave into an undeniably remarkable phenomenon in world literature. Among those who have won recognition as powerful women writers despite not being awarded the Akutagawa Prize, the work of Mari Akasaka immediately comes to mind. Her and her contemporary peers’ accomplishment becomes even more remarkable when considering the high popularity of fiction in the form of manga in Japan and its numerous adaptations into animation. Despite the visual saturation of the entertainment market, women writers continue to uphold and revitalize the written word as a platform for meaningful engagement in the twenty-first century.

Japanese women writers continue to uphold and revitalize the written word as a platform for meaningful engagement in the twenty-first century.

Continuing to enrich the literary landscape are even younger women writers like Coreco Hibino. An excerpt from 100% Momo is included in this issue. Hibino’s unique voice reflects the influence of two major sources. On one hand, she draws inspiration from Japan’s highest literary prowess, Nobel Prize laureate Kenzaburō Ōe. On the other hand, and to the same degree, her writing also exhibits earthy, unpolished elements reminiscent of raw rap music.

At the same time, other forms of writing also emerge and reshape Japanese women’s literature. A recent and emblematic event showcasing the radical shifts in Japanese fiction by women authors was the controversial admission by Rie Qudan. During the 2024 ceremony where she received the Akutagawa Award, she disclosed her use of generative AI in the writing process. While this revelation may seem problematic, it also signifies women’s prominent role at the forefront of contemporary literature in Japan, even as the literary medium itself undergoes radical transformations.

University of Oklahoma