Breaking Gendered Expectations in Japanese Lit

Though it’s impossible to say which generation of Japanese women writers has had a larger influence on literature domestically and internationally, the noticeable changes from twentieth- to twenty-first-century writers reflects the continued presence and importance of feminism internationally as women continue to move out of the spaces given to them within a male-dominated field.

Many of the names that come to mind when speaking of popular Japanese literature are, unsurprisingly, male: Osamu Dazai, Yukio Mishima, and the ever-prevalent Haruki Murakami are some that often appear at the forefront of international conversation. However, throughout Japanese literary history, the existence of women writers as leading voices is deep-seated. From Murasaki Shikibu’s iconic eleventh-century work The Tale of Genji to contemporary writer Mieko Kawakami, women writers remain a constant—if often ignored—component of Japanese literature. As Japanese literature reached new heights of popularity internationally in the twentieth century, the cohort of women writers of the era also faced success. Banana Yoshimoto, Yōko Ogawa, and Hiromi Kawakami, for example, had works translated into various languages and showcased the unique perspectives of Japanese women to an international audience. Their stories acted as a welcome contrast to Japanese male authors of the era, whose portrayal of women often ranged from dismissive to misogynistic.

Although well-loved and influential, these twentieth-century authors usually focused on spaces, characters, and themes relating only to womanhood and targeting a female audience. Yoshimoto’s Kitchen, Ogawa’s Pregnancy Diary, and Kawakami’s Strange Weather in Tokyo showcase this aspect of their writing, following women characters in conventionally female-oriented settings, workplaces, and plots as cooks, mothers, and love interests. A focus on womanhood was perhaps a welcome and necessary topic for women writers to tackle in the twentieth century, when they were largely considered a minority voice. However, the demographics of Japanese literature have changed drastically throughout the twenty-first century. The Akutagawa Prize, the most significant literary award in Japan, has greatly favored women writers since the early 2000s, suggesting that the newest generation of Japanese writers has an increased number of women that rivals the new cohort of male writers.[i] With this increase, contemporary Japanese women writers need no longer take on the role of “the female perspective” to contrast with the leading male authors who dominate the country. Instead, they naturally use their experiences as women within Japanese society to explore diverse settings, genres, characters, and themes.

The current cohort of women writers in Japan stands apart in their portrayal of alienation by combining their experiences as women in Japan with observations on the treatment of individuals who do not conform to societal standards.

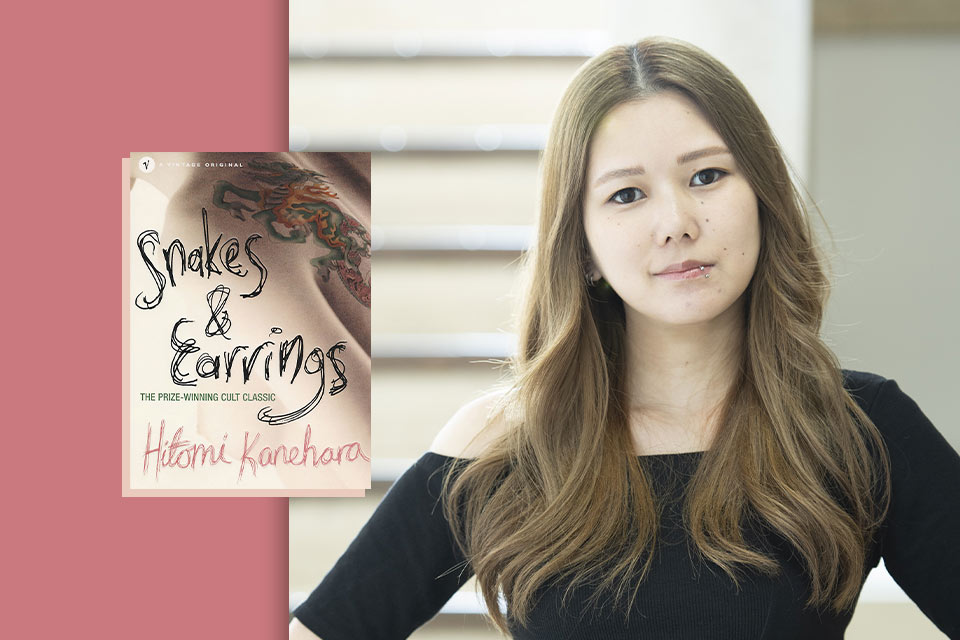

One leading theme among contemporary Japanese women writers is alienation. Alienation has been written about by many of the great male Japanese writers of the twentieth century, and women writers have also grappled with alienation for decades. However, the current cohort of women writers in Japan stands apart in their portrayal of alienation by combining their experiences as women in Japan with observations on the treatment of individuals who do not conform to societal standards. Therefore, contemporary Japanese women writers act as a bridge between the discussions started by twentieth-century women writers and the genres and plots previously dominated by male writers. With the increase in the number of women writers gaining success in Japan, many writers explore this theme of alienation in their works. Mieko Kawakami and Hitomi Kanehara are two examples of authors who have achieved rousing success with their novels overseas as well as in Japan. Each of their works, Mieko Kawakami’s Heaven and Hitomi Kanehara’s Snakes and Earrings, explore alienation uniquely and come to varying conclusions about its cause, effectiveness, and importance within society.

Arguably the most popular female author to gain international success in recent years is writer Mieko Kawakami, known for iconic works such as Breasts and Eggs and Heaven. Within Japan, Kawakami began her rise to fame when she won the Akutagawa Prize for her novella Chichi to ran (Breasts and Eggs) in 2008. This controversial work shocked Japanese readers with stark commentary on bodily autonomy, plastic surgery, and the alienation women face as their bodies age out of youthful “attractiveness.” The novella follows a young girl and her mother, who both deal with societal expectations about body, hierarchy, and choice at different stages in their lives. Kawakami rewrote and added to the novella in 2019 to create Natsu monogatari, which was translated into English by Sam Bett and David Boyd with the original title Breasts and Eggs. The translation skyrocketed Kawakami’s name to the international stage as a leading Japanese feminist writer, placing her alongside the names of twentieth-century women writers.

While Kawakami's success came primarily from this title of feminist writer, she speaks of her desire to break outside of that label in various interviews: “I got tired of being called a feminist author. . . . I want to be understood as a human writer.”[ii] Breasts and Eggs fits nicely alongside the themes, settings, and characters found in her twentieth-century predecessors, but her other works display this desire to write about a variety of themes without being pigeonholed by her gender. Heaven, in particular, explores alienation from the perspective of a bullied young boy. Written in 2009 and translated to English in 2021, Heaven asks why certain individuals are forcefully alienated from—and by—their peers. The narrator, nicknamed “Eyes” because of a lazy eye, is relentlessly and violently bullied by his classmates. He befriends a fellow victim of bullying, Kojima, who is known in their class as “dirty” for being from a lower-class family. As the novel recounts their experiences with their bullies and each other, the characters question why they are the chosen victims of abuse and what their reaction to said abuse should be.

Kawakami succeeds in creating a work that transcends “feminist literature” with bold depictions of discrimination, abuse, and alienation toward both genders.

In Heaven, Kawakami succeeds in creating a work that transcends “feminist literature” with a male protagonist and bold depictions of discrimination, abuse, and alienation toward both genders. Eyes is a disabled character who holds few of the characteristics most praised among children, such as attractiveness and intelligence. Kojima is considered dirty for not adhering to beauty standards and for failing to hide her lower socioeconomic background. Both characters are treated as outcasts from society due to uncontrollable aspects of their life, and, while not explicitly feminist, the examination of the ways societal expectations influence children’s treatment of other, more powerful children—such as straight-A student and head bully, Ninomiya—reflects the unbalanced power dynamics found in the adult world between men and women. The climax of the novel, in which the bullies attempt to force Eyes” and Kojima to have sex in front of them, suggests that the removal of bodily autonomy plays a large role in the disempowerment and alienation of the children, a concept often explored in feminist writing.[iii] Therefore, although Heaven acts as a rejection of the title “feminist author” by Kawakami, her experiences as a woman influence her portrayal of alienation and show a maintained awareness of the groups most often forced into the periphery. Heaven is proof that women writers can write outside of the traditional settings and genres written by women while still recognizing the struggles of alienated groups.

Kanehara proposes an alternative to the norm that involves violence and self-harm as acts of rebellion.

Hitomi Kanehara is, in many ways, a wildly different figure from Kawakami. After dropping out of school, Kanehara won the Akutagawa Prize for her debut novel, Snakes and Earrings, in 2003 at age twenty-one, a decade younger than Kawakami. Winning the Akutagawa Prize catapulted her into success at a young age and situated her as a voice of Japanese youth culture. The protagonist of Snakes and Earrings, Lui, is a young girl herself who is pulled into a world of body modification and sexual violence after deciding to start the process of splitting her tongue, which involves stretching a tongue piercing with larger and larger gauges. As she works toward this goal, Lui enters into an affair with the tattoo parlor worker, leading to acts of sexual violence and self-harm. Throughout the novel, Lui partakes in self-destruction as an act of rebellion against the expectations placed on young people, especially women, in Japan. Before she alienated herself from mainstream society, having a desirable and commodifiable body was the only contribution she was expected to make within society, working as a “companion” to high-end businessmen at dinners.[iv] By destroying her body and voluntarily alienating herself from this previous life, Lui challenges the commodification faced by youths entering adulthood.

Snakes and Earrings, like Kawakami’s writing, lives well outside the spaces of “women’s literature.” Instead, Kanehara proposes an alternative to the norm that involves violence and self-harm as acts of rebellion. Rather than following in the footsteps of twentieth-century women writers, Kanehara’s novel follows in the footsteps of Ryū Murakami, who is known for his shocking, vulgar, and effective prose about the underbelly of postwar Japan. However, Snakes and Earrings differs from Heaven and Breasts and Eggs in its exploration of alienation as a voluntary rejection of societal expectations rather than a forced outcasting. The theme of bodily autonomy in Snakes and Earrings also comes to different conclusions, as alienation leads to a reclamation of autonomy by Lui. Even so, these differences only further show how the expansion of setting and character types among twenty-first-century women writers leads to varying outcomes about themes such as alienation.

Mieko Kawakami and Hitomi Kanehara question the causes, types, and consequences of alienation, both from a feminist perspective and as a broader commentary on social norms. In Breasts and Eggs and Heaven, Kawakami examines the loss of perceived bodily autonomy and worth as characters are alienated from their peers. Heaven, in particular, reflects the harsh hierarchies of the adult world among children through the power imbalance between bullies and their victims. By exploring causes of alienation such as class and disability, Kawakami steps outside the genre previously expected from women writers and broadens the scope of her writing to include themes such as mob mentality, nihilism, and disability awareness while maintaining a nuanced feminist stance. Kanehara, in Snakes and Earrings, explores the voluntary alienation that youths in Japan choose for themselves and the destruction of the body as a reclamation of bodily autonomy from the jaws of mainstream culture. While both writers contemplate the theme of alienation, the circumstances and consequences of each protagonist’s alienation vary wildly. This diversity in the treatment of similar topics acts as further proof that with the diversification of genre, character, and setting has come the expansion of ideas outside of those found in “feminist literature” or “women’s fiction.”

Kawakami and Kanehara question the causes, types, and consequences of alienation, both from a feminist perspective and as a broader commentary on social norms.

It is impossible to say which generation of Japanese women writers has had a larger influence on literature, domestically and internationally. Furthermore, I would not argue that the current generation is inherently better than twentieth-century women writers because of the diversification of genre. In the late twentieth century, feminism had just reached mainstream Japanese consciousness, and the serious contemplation of the experiences of women within female-dominated spaces was necessary work.[v] Without Banana Yoshimoto, Yōko Ogawa, Hiromi Kawakami, and others, the influx of women writers in the twenty-first century likely would have never happened. However, the noticeable change from this previous generation of writers to the current one further reflects the continued presence and importance of feminism internationally, as women continue to move out of the spaces given to them within a male-dominated field to inhabit increasingly multifaceted literary forms.

Shinkamigoto, Japan

[i] “Little Surprise as Women Win Japan’s Prestigious Literary Prizes,” Japan News, July 22, 2022.

[ii] Joshua Hunt, “‘Breasts and Eggs’ Made Her a Feminist Icon. She Has Other Ambitions,” New York Times Magazine, Feb. 7, 2023.

[iii] Mieko Kawakami, Heaven (Picador, 2022), 147.

[iv] Hitomi Kanehara, Snakes and Earrings (Dutton, 2005), 53.

[v] Fujita Taki, “Women and Politics in Japan,” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 375 (Jan. 1968): 91–95.