Myth 2.0: Multimedia Projects of Central Asia

Myth lives on in Central Asia, but it has changed shape. Through multimedia projects, audiences become participants in rituals rather than mere participants, and multimedia artists create myth anew.

If you think of myth as something long left behind—lost in the shadows of antiquity, hovering at the threshold of literacy, wrapped in archetypal mist—it might be time to take a closer look at multimedia projects from Central Asia. In many ways, myth is still alive here. It has simply changed shape—shedding its skin, adopting a new interface, a new medium. Or so it strongly appears. Instead of firelight, we now have projection screens; instead of the shaman’s drum, we hear tactile acoustics and subwoofers embedded in the floor. The caves of old have become the black boxes of galleries or the blank void of a stage. Paradoxically, the more technologically advanced the artistic language becomes, the more magic it seems to contain. Once again, we find ourselves searching for archetypes—only now they come to us in the form of glitch graphics, choral breathing, generative patterns, and bass vibrations that travel straight through the ribcage. In this sense, multimedia projects become a kind of modern-day mystery rite. For thirty or ninety minutes, the audience is no longer an audience, but a participant in a ritual that requires neither belief nor understanding—only presence. These rituals are gaining traction across Central Asia, and it may well be this subtle, unspoken function that explains the growing appeal and cultural value of multimedia art in the region.

Paradoxically, the more technologically advanced the artistic language becomes, the more magic it seems to contain.

Terminology in Transit: A Quick Dive into Practice

There is no shortage of synonyms for what we now call a “multimedia project.” And there’s good reason to unpack this terminological abundance—because behind each term lies not just a genre label but an entire ideological framework: what contemporary art talks about, how it speaks, with whom, and to what end.

These works may be labeled as art or project, modified by adjectives such as multimedia, media, cross-media, or new media, as in teamLab Borderless (Japan, 2018) or Riot, by Karen Palmer (UK/US, 2017). Somewhat more specific are terms like interactive, immersive, transdisciplinary, digital, or art-tech, which point not only to a layering of expressive tools but to the mode of audience engagement, the depth of technological integration, and—at times—the very logic of artistic thinking itself.

In the case of interactive, the focus is on audience participation: the artwork responds to touch, movement, sound, or choice, turning the viewer into a co-creator. Notable examples include The Treachery of Sanctuary, by Chris Milk (US, 2012); Pulse Room, by Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (Canada/Mexico, 2006); and DOKU: The Self, by Lu Yang (China, 2021).

In immersive projects, the emphasis is on total immersion—not merely observing but being physically, emotionally, and sensorily inside the work. Consider Berl-Berl, by Jakob Kudsk Steensen (Germany, 2021); The Infinite Crystal Universe, by teamLab (Japan, 2018); Meow Wolf: House of Eternal Return (US, 2016); or Very Frustrating Mexican Street, by Samson Young (Hong Kong, 2019).

The term transdisciplinary signals a crossing of disciplinary boundaries, as in S/N, by Dumb Type (Japan, 1994); A Journey through Spacetime, by Ellen Pau (Hong Kong, 2021); and Assemblance, by Umbrellium (UK, 2014).

Meanwhile, digital refers to the material basis of the work—where digital technologies evolve from tools into the very structure of the art itself. Examples include Unsupervised, by Refik Anadol Studio (USA, MoMA, 2022); Fragments of Future Histories, by Tsang Kin-Wah (Hong Kong, 2019); and Forest of Resonating Lamps, by teamLab (Japan, 2016).

When such technologies become “high”—think neural networks, VR, sensors, blockchain, or generative algorithms—we enter the realm of art-tech. Here we find projects like Quantum Memories, by Refik Anadol Studio (Australia, 2020); WHIST, by AΦE (UK, 2017); the Living Architecture Systems Group (Canada, 2022); and The Fabric of Reality (UK, 2020).

According to the Archive of Digital Arts, more than six hundred festivals around the world engage—directly or indirectly—with new media.1 This is not merely a matter of numbers. What’s striking is that media art seems to resonate with patrons and sponsors in ways that other art forms don’t always manage. Its discursive magnetism spans academic journals and glossy magazines alike, and its presence on the most progressive cultural platforms is no longer the exception but the rule. Moreover, media art increasingly finds itself at the intersection of creativity and commerce. There are numerous instances where such projects have evolved into sustainable ventures, borne of collaborations between artists and technology companies—mutually enriching, rather than compromising, either side. Take, for example, Samsung Electronics’ long-standing support for digital installations, or the inclusion of media art in the auction offerings of Phillips, where immersive and generative works are now gaining serious market traction.

Descent into Central Asia

Central Asia is still perceived as something of a blind spot on the global cultural map—in my view, undeservedly so. Over the past five years, the region has witnessed the emergence of several major multimedia projects—each reflecting a distinctive approach, while collectively weaving together art, science, technology, and cultural heritage. The chronological arc of some of these projects unfolds as follows:

Beethoven.Mute (Kazakhstan, Almaty, 2020). A multimedia meditation on silence, legacy, and listening—anchored in Beethoven’s world yet echoing into Central Asia’s own cultural soundscape

Art Collider (Kazakhstan, Almaty, 2021). An interdisciplinary art-and-science school aimed at engaging critically with the cultural landscape of Central Asia

Buqtarma Discovery Camp (Kazakhstan, East Kazakhstan Region, 2021). An experimental tourism initiative combining business, leisure, and the development of local ecotourism through immersive experiences

Aruu Ene Batasy (Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, 2021). A multimedia exhibition devoted to the tradition of bata—a ritual blessing central to Kyrgyz cultural identity

Kyrgyz Özögü – Oy Ile Taasyry / To Keep Our Roots, Without Losing Time (Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek, 2021). An exhibition exploring the dynamic tension between tradition and modernity in contemporary Kyrgyz society

Babalar Press (Kazakhstan, 2022). An independent publishing and artistic platform inspired by ancestral voices and future imaginaries

Korkut Biennale (Kazakhstan, Almaty, 2022). One of Kazakhstan’s landmark events for sound art and experimental music, named after the legendary figure Korkut Ata

Preserved Nature (Azerbaijan, Baku, 2023). An ecological art project merging aesthetics and environmental consciousness in response to the climate crisis

Jadids: Letters to Turkestan (Uzbekistan, Tashkent, 2024). A multimedia exhibition dedicated to the Jadid movement and the intellectual history of Central Asian reformers

Ma’na Lab (Kazakhstan, Almaty, 2024). A transdisciplinary lab for artists, writers, and activists across Central Asia, fostering collaboration and critical imagination

Each year, multimedia projects in Central Asia embrace more advanced technologies, ecological themes, and interdisciplinary strategies. Quietly but steadily, they are reshaping the cultural landscape—and perhaps even more profoundly, the inner landscape of the younger generation. Today, many young creatives feel less urgency to leave the region; in fact, for many, Kazakhstan—and Central Asia more broadly—has become one of the most compelling places to be. Before the Korkut Sound concert, Anvar Musrepov, curator of the first Central Asian Sound Biennale and a student at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, remarked: “Yes, classes are in session in Vienna right now—but being here matters more to me.”

For many young creatives, Kazakhstan has become one of the most compelling places to be.

The enchantment of multimedia projects often stems from concepts that tap directly into transcendent experience. A vivid example is the first Korkut Biennale for Sound Art, in which I had the honor of participating. It’s a fitting case to mention—not only because of its visionary premise but also because the second edition is set to take place this autumn, with a newly transformed concept and curatorial approach. You’ll have the chance to experience it for yourself.

The main organizer of the biennale is Tselinny, a contemporary art center in Almaty made possible through private patronage—an increasingly vital model for cultural infrastructure in the region. It is no coincidence that the biennale bears the name of Korkut—a figure who is part historical, part mythical, and wholly emblematic. In Kazakh cosmology, Korkut exists in a liminal state: neither alive nor dead, like an atom in quantum superposition. The symbolism is intentional, and resonant.

The curators of the first biennale were quick to clarify: “This isn’t music, it’s sound art.” But why not call it music? It was music—through and through—with thought, emotion, technique, technology, beauty, and a kind of magic. The program featured three concerts, five site-specific installations, a series of artist talks, and an exhibition. At its core, the biennale revolved around a search for a different mode of sensing the world. In an attempt to reenchant reality, sound artists collaborated with natural forces, algorithms, and other nonhuman agents—dissolving the boundaries of the real and inviting the audience into a sonic immersion that bordered on the transcendent.

The Korkut Sound concert unfolded in three distinct acts—three sonic concepts, three ways of listening, three unique forms of musical communication. Yet all of them spoke in the language of Kazakh timbres and textures. The first set came from Kokonja—a fragile and frighteningly gifted young woman of the kind for whom formal music education would likely be hazardous. She doesn’t interpret music; she inhabits it. She feels it through the skin. She is, in a sense, music’s own avatar. Her performance was built on sounds she had personally collected during field trips—cave acoustics, the shifting of sand dunes, collisions of wind and matter recorded during her solitary expeditions. The elements she summoned onstage weren’t controlled through sophisticated digital interfaces but through a small, almost toylike wind instrument, into which she whispered secret rhythms and delicate fragments of noise. With an eight-channel spatial audio system and the audience arranged in a circle, the sound wrapped around and within you—until you no longer felt like a listener but like the circulatory system of the music itself. It was a kind of sonic magic.

The second set surprised the audience with a technical solution that felt both timely and completely organic to the performer. Adil Kaírden performed on . . . a mobile phone. Yes, that was his instrument—and the one on which he usually composes. A specially designed app allowed him to control audio layers, pitch, dynamics, and spatial distribution. The algorithmic code responded to the phone’s gyroscope—tracking tilt, direction, and velocity in real time. The recorded tracks, layered into the performance, featured the kobyz playing of Satkozy Mukhtar. Musically, the performance was open to debate. There were inevitable moments of unevenness, as might be expected in a debut. But the conceptual boldness—and its technical implementation—was nothing short of promising. Intriguingly so.

The evening’s headliner was Hongshuo Fan, an artist and electroacoustic music researcher based in Manchester. His performance featured a duet between a musician (dombra player Daulet Zhanshin) and a machine (a neural network) in a live multimedia composition titled Conversation in the Cloud. One lingering mystery for the audience was the training material: on what music, exactly, had the neural network been fed? Whatever the dataset, the result was stunning—sonically, visually, conceptually. Seated close to Hongshuo Fan, I watched the neural network in action, visualized in part as a digital dombra player. The algorithm’s internal processes, displayed in real time, were no less captivating than the official video stream—generative graphics translating the dombra player’s hand movements into radiant abstraction. The dramaturgy and formal logic of the piece were perhaps a bit too transparent. But then again, the structural simplicity served as a counterbalance to the performance’s technological density. It worked.

Music of Realization 41

I can speak about the next biennale concert in greater detail because I was one of the co-authors of its concept. Titled Music of Realization 41, it was built around the idea of chance. This multimedia concert also functioned as an experimental research platform, exploring multilayered collaboration between the contemporary music ensemble EEGERU, the techno club bULt, and media artist Dmitry Morozov (::vtol::). The underlying idea has existed—and been realized in various forms—throughout the history of music. The most obvious parallel is aleatoric music, which many twentieth-century composers embraced: John Cage, Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, among others.

Asel Shaldybaeva, co-author of the MO41 concept, described the project as an attempt to grasp the nature of reality itself—through a collective act of gazing into the meanings of random symbols and listening to the form that sound assumes in their wake. A sacred ritual rendered as total sonic performance, MO41 brought together industrial soundscapes, the traditional divination practice of kumalak, and electroacoustic music. For nearly a year, we searched—philosophically, scientifically, technically—moving by intuition, listening deeply to ourselves, to the world, and to one another. The idea of chance finds resonance across multiple domains—mythological, philosophical, scientific, psychological, artistic—and all of them were activated within MO41. We truly did not know what the performance would sound like in real time. No one did. Because the music was guided by kumala.2 The nine-field kumalak board traces its origins to Sumerian-Akkadian mythology, where, according to legend, Enlil—the Lord of the Wind—bestowed upon humanity the immutable Great Law of the World, inscribed upon the board itself. This law did not dictate human behavior but rather described the architecture of cosmic order, offering knowledge that could be applied to all dimensions of life.

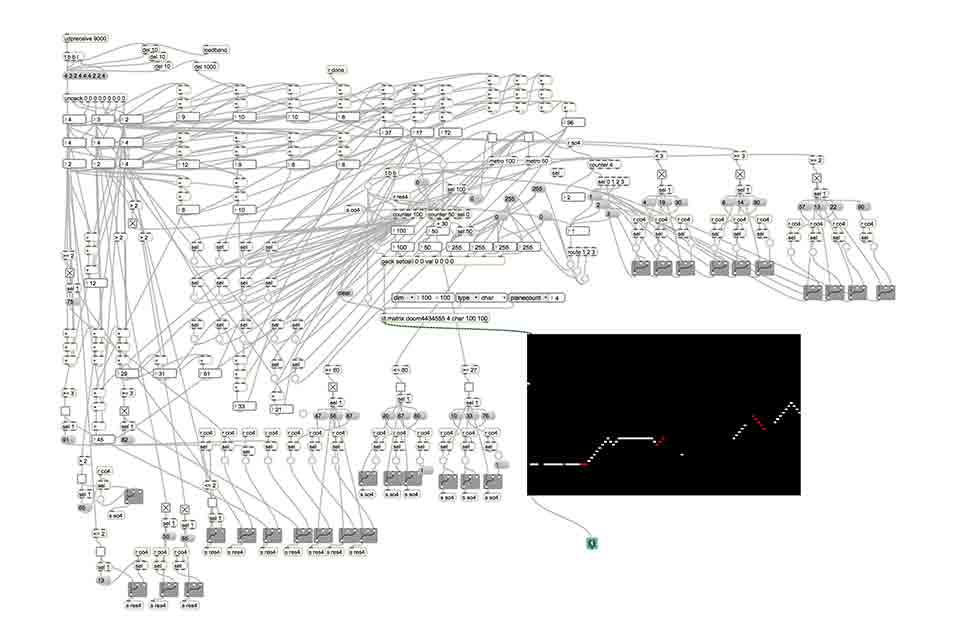

The transformation of divination into a graphic score unfolded through a set of custom-designed tools—both hardware and software—created specifically for the performance. During the kumalak reading, a camera mounted above the board captured the position and number of stones in each square. This visual information was then processed by an algorithm, which analyzed the numerical and spatial arrangement within each cell and generated individual graphic scores for each performer. The drawing below captures a visual rendering of the software’s translation of kumalak configurations into musical notation.

As a result, the project took shape as a technologically layered system involving:

a kumalakshy practitioner, trained to cast kumalaks in full accordance with traditional rules, including the mathematically precise number of possible combinations—three separate kumalak readings formed the tripartite structure of the performance;

a fulfilment engineer, who developed the algorithm translating kumalak configurations into graphic scores for each instrument;

six acoustic instruments—violin, viola, cello, flute, clarinet, and, crucially, kobyz, whose presence was conceptually essential;

a composer-mediator, functioning as the performance’s connective tissue, working with a palette of noise textures and Tibetan singing bowls that migrated across all six scores;

an electronic musician, who joined in for the second and third kumalak readings, performing across all six instrumental layers simultaneously;

two manually piloted drones, self-assembled and mounted on vertical tracks, which provided a separate layer of noise texture;

and finally, neural network-generated predictions, handed out as small oracular texts to each listener and participant.

Attention has become the rarest of resources, and the artist responds by creating experiences in which the viewer becomes a co-author.

What Lies beyond the Horizon?

The growing involvement of the Central Asian art scene in metacultural projects is already speaking in the language of a new generation: the language of the twenty-first century, and perhaps even of the twenty-second and twenty-third. And in this language, there is something deeply familiar: Kazakh, Turkic, elemental. In part, this is because it speaks to myth—and because it creates myth anew.

Among the multimedia projects announced for 2025 are Ancient Futures (Tashkent, Uzbekistan), which merges traditional crafts with biodesign in search of responses to the climate crisis, and Korkut Triennale 2025 (Almaty, Kazakhstan), the second edition of the sound art and new music biennale, this time titled Rites of the Eternal Wind.

Attention has become the rarest of resources, and the artist responds by creating experiences in which the viewer becomes a co-author. Myth returns—not as story, but as sensation. Not as figure, but as shadow. Not as text, but as vibration. And in a world where individuality has become a cult and loneliness a pandemic, that may sound like a kind of solace. Perhaps the most avant-garde project today is not about the future at all—but about a deep, ancestral memory of who we once were. And who we might still become.

Almaty, Kazakhstan

“Festivals,” Archive of Digital Arts, retrieved from digitalartarchive.at.

Kumalaks are a traditional Turkic form of divination using forty-one small stones. They are employed to interpret fate, inner states, and unfolding events—often blending elements of philosophy, cosmology, and shamanic practice.