Agnieszka Holland’s Complicated Kafka

A writer and musician from Gdańsk, Poland, Grzegorz Kwiatkowski collaborated on Franz with Agnieszka Holland, a filmmaker who in the dark times of the Communist regime left Poland for Prague out of love for Kafka. Kwiatkowski considers the film’s universal relevance as democracy is attacked and finds a film ultimately as enigmatic as Kafka himself.

A few years ago, in a conversation with Peter Constantine for World Literature Today about my book Crops, we also spoke about the nearly half a million pairs of shoes taken by German executioners from Jewish prisoners murdered in Auschwitz (WLT, Sept. 2022, 34). A large portion of those shoes still lies rotting in a forest near the former Stutthof concentration camp, which served as a center for repairing leather goods and footwear for all the concentration camps in Europe. Those shoes are still there, decomposing, despite hundreds of alarms, media reports, and conversations with officials and authorities.

The traces of the massacres of World War II remain visible. We are unable even to secure and preserve them, and yet we have entered a new era of wars and slaughter in Ukraine, in Gaza, in Sudan, in Yemen. Of course, after 1945 there was no lasting peace. There were bloody conflicts and genocides, but I had the impression that after each of them, humanity and public opinion felt some shame, beat their chests, and sincerely said: Never again. Now, I feel that this shame has—not completely but to a large extent—disappeared. Responsibility has vanished, and we are simply starting to get used to it, which may mean that the number of wars and massacres will grow, because the public and voters simply accept this new bloody state of things.

It is a pity that we did not look more closely at those forest artifacts of annihilation, murder, and violence, because they are like a mirror. This is no great secret or discovery. The heart of darkness is not found primarily outside but within ourselves, and each of us carries within a potential for violence, murder, denial of guilt, and self-justification. After all, most perpetrators of genocide claimed and still claim that they were potential victims, that they killed women and children because otherwise those children would grow up and try to kill them. Humanity as a species has conquered the entire planet, exploiting it and one another, because that is its predatory, aggressive nature.

Humanity as a species has conquered the entire planet, exploiting it and one another, because that is its predatory, aggressive nature.

I must admit that I am deeply disappointed, perhaps with my own naïveté, because I thought that through education, through the shock of the Holocaust and World War II, we would be able to confront our murderous demons and protect ourselves and others from what we carry within. The last few decades may indeed have brought fewer wars than earlier eras, but it seems we are returning to the same deadly path.

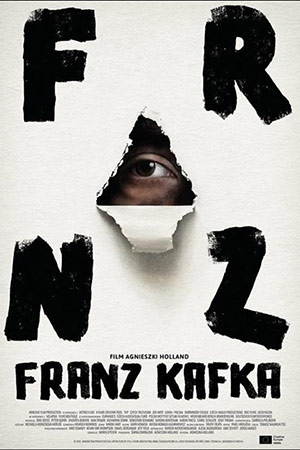

Why am I mentioning all this? Because I want to write a few words about the greatest writer of central and eastern Europe, in my opinion the greatest writer in history: Franz Kafka. He himself was not murdered, but his sisters were, by the Germans, in Chełmno and Auschwitz during the Holocaust. I want to write about Kafka because of the new film by the brilliant director Agnieszka Holland, who in the dark times of the Communist regime left Poland for Prague out of love for Kafka and studied there at the film school together with Miloš Forman.

But why should I be the one to speak about this? I will try to justify it.

I know Agnieszka Holland personally, and the music of my band, Trupa Trupa, is part of this film. Agnieszka also used our music in her earlier film Green Border, which won the Special Jury Prize in Venice. But that is not the only or the main reason.

The main reason lies in childhood. Long ago, in winter, in Gdańsk, I was seven years old and in love with my sneakers. My parents asked me every day to wear winter boots. I refused. The sneakers were beautiful, the winter boots ugly. One evening my father said that if I did not change them, he would take me to the orphanage in Gdańsk’s Orunia district. I packed my backpack, said goodbye to my sister, and went with my father to the bus stop, where the B-line bus arrived. I knew that orphanage because we had once lived nearby, and I knew that the B-line went there. When the bus arrived, I ran away. I cut through a nearby cemetery and got home before my father. We never spoke of it again. And most importantly, I do not remember what shoes I wore to school the next morning.

Later I read Kafka’s Diaries. A boy asks his father for a glass of water. The father loses patience, puts him out on the balcony, and locks the door. Kafka writes that at that moment, his life ended.

It seems to me that there have been and still are many such stories. It was simply a certain harsh, eastern European way of upbringing and, before the twentieth century, a global one. Parents acted this way, and unfortunately, to a large and still far too large extent, they still do. In any case, you had to accept it. And perhaps it really was your fault, not theirs. That is what I mean: the search for the heart of darkness and evil arises within oneself from the very beginning, even when, in specific cases, the blame should be distributed differently.

Since then, Kafka has become a key artist and spiritual guide for me. Many years later, during a writing fellowship in Vienna, I often went to Kierling, where Kafka spent the last weeks of his life. The sanatorium is now a small museum, and on the walls hang charts of his body temperature. I keep returning to Kafka, to new translations and biographies. And everything always takes on new meaning, because this brilliant central European writer was a master of ambiguity, never of dogma.

Agnieszka Holland was just as formative for me as Kafka. As a teenager I saw her film Total Eclipse. It was brilliant, unforgettable. Arthur Rimbaud, played by DiCaprio, was extraordinary. That film pushed me toward literature. In a sense, it made me a poet and a writer. Later, Agnieszka and I became friends. And then came collaboration.

I did not know what her new film would be like. It turned out to be as enigmatic as Kafka himself. Holland does not tell us who Kafka was. He himself probably did not know. Like all of us. Holland builds a polyphonic narrative, moving between his time and ours. She shows him from many sides, through many voices. Idan Weiss plays Kafka as brilliantly as DiCaprio played Rimbaud. And of course there is the Father. The great, terrifying Father. Terrifying, but perhaps also caricatured and awkward, played excellently and masterfully by Peter Kurth.

During those scenes, I thought of my own father. When I spoke about ecology or vegetarianism, he replied, “In my day, when too many puppies were born in the village, they were buried in manure.” When I talked too much about art or behaved eccentrically, he said, “Because it is easy to play the clown.” And you just accepted such things. You felt bad but took it as a just verdict, because in a way he was right, and it was indeed as he said.

Not far from my family home in Gdańsk, in a manor in Srebrzysko, lived Joseph von Eichendorff, author of The Life of a Good-for-Nothing. The father of the main character throws him out of the house for laziness and recklessness, and the son becomes a wandering artist. Such coincidences always made the sense of guilt stronger and, at the same time, desirable, not negative, because ultimately the main character chooses the world of art.—that is, the world of freedom and self-determination.

Forgive my autobiographical digressions, but I am not a film critic. I am a storyteller, a writer. I want to say something about Kafka, about Holland, but also explain why I am speaking and where I am from. I am from Gdańsk, where World War II began. I am from Gdańsk, where the hope of the Solidarity workers’ movement was born, which, led by the great hero Lech Wałęsa, brought about the fall of the Communist system in Europe. And I am also from Gdańsk, located just a few dozen kilometers from Russia’s Kaliningrad region.

Agnieszka Holland once told me that the vaccine of the Holocaust has stopped working, that people have forgotten what they are capable of. I would like to disagree with her, but it is true. Democracies are being dismantled. Even left-wing politicians today mostly speak the language of anti-immigration and exclusion. The killing of women and children no longer shocks us deeply; we have largely become used to it.

Milan Kundera once wrote about the kidnapping of central Europe by predatory Russia. Today it seems that it is democracy itself that is being kidnapped, methodically, without fireworks, and quite quickly. And it is happening in almost every country in the world.

Czesław Miłosz suggested that artists from our central and eastern region had an advantage over their western peers. They lived in criminal and oppressive systems that revealed the true potential of humanity, and we were wiser for that dark knowledge. Holland’s Mr. Jones, a brilliant film about the Holodomor, the famine planned by Russia in Ukraine in the 1930s, is one record of that knowledge.

But Franz belongs to a different current of her work. Franz is not an intervention, not reportage. It is, like Total Eclipse, a work of art that is moving but at the same time rejects simplifications. And I think that Kafka in Holland’s film is, in a sense, ordinary. He has obsessions, limitations, fears, fascinations, and loves, like all of us. His neurodivergence is now almost universal, because who among us is truly normal? Everyone has something, everyone is different, and that is precisely the new, wonderful norm, a new, wonderful norm that so deeply irritates the far-right moralists who want to see the world in black and white.

The nature of Kafka, shown by Holland in many aspects, forms a portrait of a kind of amateur scientist who observes himself and us as if in a laboratory, stripping us of illusions. But Kafka in Holland’s film is also full of absurdity, irony, and normalcy.

And it seems to me that absurdity has special meaning here. This absurdity is not treated as a shock but as a norm. Because here, in central and eastern Europe, absurdity is almost a norm, here, where borders, rules, and laws have constantly changed. Timothy Snyder, by calling his book about this region Bloodlands, captured the brutal essence and most painful consequence of these historical shifts. I think absurdity, together with guilt and the state of lost innocence, without melodrama or self-pity, is what most reminds me of Kafka. Kafka’s world is partly absurd, horror, and obsession, but ultimately in cold, emotionally neutral tones. That coldness here is simply, and to a large extent, something normal.

I think absurdity, together with guilt and the state of lost innocence, without melodrama or self-pity, is what most reminds me of Kafka.

At the end of Franz, we hear a recording from the answering machine of the Kafka Museum in Prague: “If you want a personal meeting with Kafka, say Franz.” Holland says the word: “Franz.”

To me, that word carries a kind of love and tenderness. In one interview, Holland said she feels that Kafka is like a brother to her, and that she feels a bit like one of his sisters and takes care of him.

I think that creating such a biographical film, one whose narrative and form break the conventions of the biographical genre, is also a form of care, an attempt to save Kafka from a rigid, predictable portrayal and the repetition of clichés.

Although everyone watches and reads through themselves, I once thought that reading and understanding Kafka solely through the lens of totalitarianism was a simplification and reduction. But the dark, dangerous, aggressive shadows in our societies and in our recent history have returned and strengthened, and today Kafka also has, for me, that dark, totalitarian shade.

I want to add, in the end, that I hope I am exaggerating. I hope it is not as bad as it once was, or worse. I hope that my former neighbor from Gdańsk, the great pessimist philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, will not have the final dark word, and that Kafka’s psychological darkness, like that in “In the Penal Colony,” will remain mostly in the realm of imagination. I am keeping my fingers crossed. And I invite you to Franz, a film that will not make it easier to look at Kafka or the world but will complicate it, ask questions, and leave us alone, and perhaps through this gesture of not instructing and of treating us seriously, perhaps it will awaken someone from lethargy and open their eyes to a world other than the polarized, black-and-white, false view.

Gdańsk, Poland