Writing on War’s Edge

Before burning them, a writer reads through his diaries to recall disappointments, failed love stories, and the details of ordinary relationships.

Whenever I think back to the beginning of this genocide, a great lump forms in my throat, because I carried out a wild and heinous act worthy of perpetual shame: I set my journals aflame and put them underneath a teapot, boiling the tea along with their accumulated memories.

In fact, this was the second time I had committed that sin—not because I was feeling mixed up inside or suffering from schizophrenia, but because I feared an even greater calamity. Gaza is public domain; nothing is off limits. The Israeli colonizer’s forces, or local thieves, could break into my house or library and take whatever they wanted, without fear of anyone stopping them. What would become of me if those multicolored notebooks fell into the hands of the criminals who have been raiding institutions and homes? What if one of them posted my diaries on social media? How would I respond if a thief laid me bare before the whole world? All of my secrets and moments of weakness published on Facebook, Instagram, or X for everyone to see? I imagine someone writing mockingly, “Revealed: The dark side of prominent Palestinian author Yousri Alghoul! These are Alghoul’s wildest moments. Get a load of the dirty laundry of Gaza’s most famous storyteller!”

Oh god! If that happened, what position would it put my siblings in? What about my other relatives and my neighbors? My friends? My female friends? What would my wife think when she learned that I was fighting with her on the page because I felt incapable of doing so in real life? What would they do to me? Burn me at the stake?

So I searched the remnants of my home for my journals and realized they weren’t there. Earlier that day, I’d mustered all my strength and composure and launched a wide-ranging military operation: I snuck through the streets and alleys of al-Shati camp like an elite soldier in a commando unit, making my way toward my house. The area was totally empty except for the Israeli drone in the sky that was surveilling our facial features, determined to assassinate the slightest smile, the tiniest touch of joy. When I arrived at the abandoned house, I found that we had left the door unlocked. After all, the area—Ard al-Ghoul in the al-Murabiteen neighborhood—was a closed military zone. With the exception of a stray rabbit, there wasn’t a creature in sight. (Later that day, I took the rabbit back with me to my parents’ house—where I was living while displaced—and we decided to keep him and make him our confidant. But he died the next day of fright from the bombings, and his spirit was snuffed out forever.)

I burned those memoirs of mine, and the taste of the tea was heavy on the heart and the tongue.

Inside the house, there was a great void. The walls were destroyed; the cabinets and the clothes and TVs—everything had collapsed into the rubble. In my library, all that was spared the pain of burning was a single bookshelf, which stood steadfast. I searched in vain among my books for my private notebooks, so focused on the task at hand that I forgot to grab the copies of my published novels that were there, which I’d finally managed to have shipped to me from Amman, Beirut, Algeria, and Egypt. This was a major feat, because Gaza is besieged, and the colonizer’s soldiers, who are as heavily armed with spite as they are with weapons, don’t like educated people. (“They don’t like butterflies either,” my friend Ahlam always says.)

I hurried back toward al-Shati camp. En route, there ensued an absurd scene worthy of Charlie Chaplin or Pat & Mat. The rabbit escaped, I chased after him, the drone launched a rocket at us, and we hid together beneath a dilapidated wall. The rabbit trembled while I held him once more, and it felt almost as though he was promising me that if we made it out of this foolish adventure alive, he’d never leave me again.

* * *

Throughout my displacement, I couldn’t stop thinking about those journals. Where had they gone? How could I retrieve those pages that meant everything to me? Then again, if the soldiers or thieves found them, would they even appreciate the significance of what they were holding in their hands? Perhaps they would simply kick them away, thinking they belonged to some woman who filled them with recipes, dates, and lists of grocery items from friends’ and relatives’ visits. So-and-so brought a bag of flour and someone else brought a box of Awda wafers—and she’d put the expiration date in parentheses. No, I wrote about nothing of the sort, but rather about serious work matters and my personal relationships with colleagues, relatives, and the authorities, those sons of . . . What if the diaries fell into the hands of one of these people and they couldn’t help but search through the pages for something to satisfy their vanity? I’m afraid they’d only find my disappointments, my failed love stories, or the details of my ordinary relationships with my fans and haters.

Never mind all that. What mattered to me was getting the notebooks back before some educated thief stole them to blackmail me, demanding a large sum of money for their return. But do thieves read? Do they care about me or my books or my dreams? Would it occur to them, in a passing moment, to read between the lines of a story that meant nothing to them? Of course not—nobody would care about my personal business. Why was I worrying myself? I don’t know.

Anyway, I was displaced to Jabalia camp after the colonizer’s forces began targeting homes near my parents’ house in al-Shati camp. They fired at us with smoke grenades, artillery, howitzers, and more. Judgment Day had arrived in our camp, and it made drunkards of us all. We fled without thinking. Forty days and forty nights later, I returned to al-Shati camp to find it completely destroyed except for a few blocks here and there.

Around that time, the Devil laid siege to me once again, planting painful ideas in my subconscious about my diaries. I decided to trek to my office in the Tel al-Hawa area to search for my buried treasure on its shelves. There were no pirates on the land to fight me with their swords, but in the air there were plenty of warplanes, reconnaissance drones, and quadcopters—another unforgettable adventure.

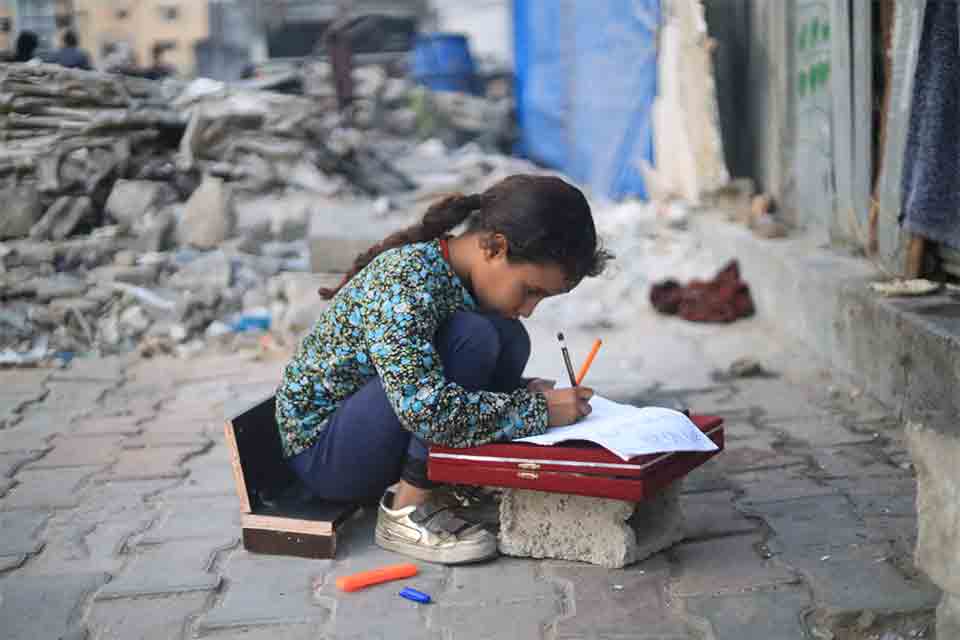

Amid the colossal destruction of northern Gaza, its people were out in donkey carts and rusty tuk-tuks, heading to unrwa schools and what remained of university buildings, which would serve as their shelters until the end of this suffering that refused to end. In this atmosphere, I started running a long-distance race: I weaved my way through the crowds until I finally arrived at my work building, which was occupied by displaced people who had come from far and wide. Goose bumps formed on my body as I walked through the door; it felt as if I had only left work yesterday. I made my way up to my office on the fourth floor, and there I discovered that my electronic devices—laptops, phones, and all—had been stolen. The thieves had only left me with a single laptop charger.

But all I cared about were my notebooks. I searched the drawers and found them at last—all three of them: a black one I got in Paris, at the offices of France 24 to be exact; a green one I bought at a mall in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia; and a red one, locally made, a gift from Ooredoo Wireless to its valued customers.

Heart pounding, I began to flip through the pages. Oh-ho! I finally had my hands on my notebooks, and my fears vanished. I returned to my parents’ house, victorious. In the room where I was staying with my family, I began to read my diaries anew, focusing on entries about incidents that had ultimately made their way into my political novel, Clothing That Miraculously Survived. I realized that the very existence of these notes put me in danger; they left me completely exposed. And so I decided, in a moment of frenzy, to burn my notebooks on the roof. In fact, it was on that very roof that I had once burnt the notebooks of my adolescence, concerning which my wife had made me a deal: either get rid of them and she’d stay, or keep them and she’d go back to live with her family. In both cases, I preferred peace, so I burned those memoirs of mine, and the taste of the tea was heavy on the heart and the tongue.

Writing is an act of madness whose practitioners live in fantasy worlds.

Writing is an act of madness whose practitioners live in fantasy worlds, drowning in unreal dreams in lands where peace is unknown, so I decided to return to writing once again. But I didn’t stop there. My esteemed publisher, the Arab Institute for Research and Publishing in Beirut, has agreed to print these new diaries as a book, Northward Displacement: An Account of Hunger and Pain. But to be honest, I don’t know if I will live to see that day or if, like many of my friends before me, I will depart this life in the blast of a depraved missile.

I still dream that the war will end. I am beginning to write these diary entries, trying to keep calm while listening to Fairuz, with whom the sound of the warplanes up above is competing. On the ground, the blood surrounds me, keeping my mind set on my journals, my books, my library . . . my house which was completely destroyed, and with it all of my stories and small victories. Will I withstand this, I wonder? One day, will I be able to grasp hold of my life, to rebuild my house and my library? Perhaps . . .

Translation from the Arabic