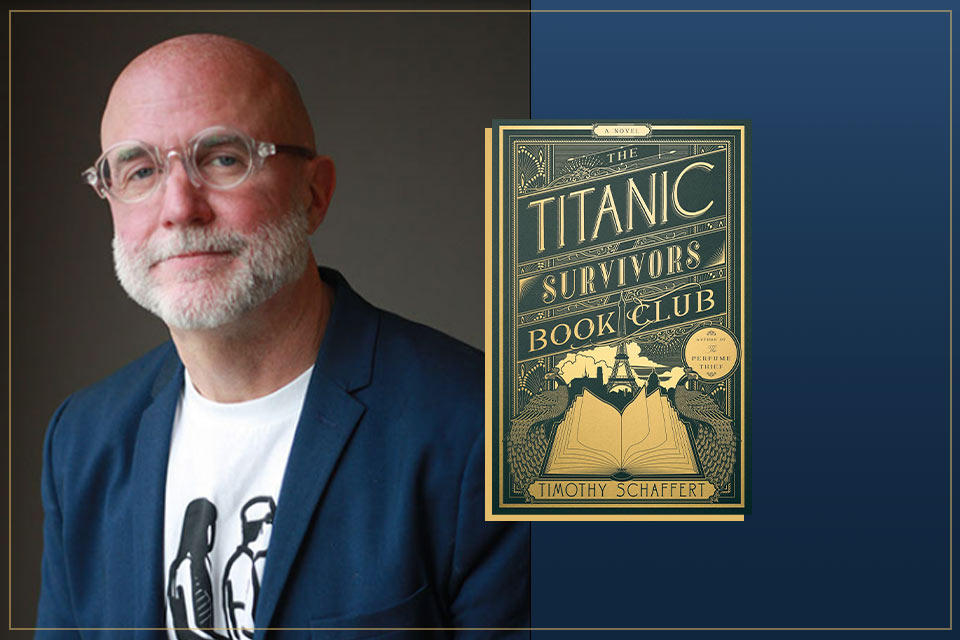

The Tragedy of the Titanic Has All the Dimensions of Fate: A Conversation with Timothy Schaffert

I had coffee with one of Nebraska’s bookbinders a few months ago. A meeting I remember with gratitude. A gifted workman, Kevin started his career in traditional literature but later went to England where he pivoted to Book Studies and earned a master’s degree in the field. His quest to fix his tattered book, as a college student in Lincoln over three decades ago, led him to a ninety-seven-year-old man who was the only bookbinder in the city at the time. As Kevin watched the man work tenderly on the edges of his book, he realized books also require care. That experience motivated him to submit himself, a few years later, as an apprentice to Lincoln’s first and only woman bookbinder then, whose love of storytelling was as inspiring as her passion for mending books.

Encountering Yorick, the bookbinder in Timothy Schaffert’s novel The Titanic Survivors Book Club, made me think of Kevin. Schaffert’s novel made me understand better the urgency with which we should approach the matter of the survival of the book. We seem to be closer to life in fiction than we know. But Schaffert knows this, and that is why he transforms the haunting aftermath of one of humanity’s most fatal shipwrecks into a text of deep intellectual and emotional longing. In this conversation, Schaffert and I discuss the inspiration and aspirations of The Titanic Survivors Book Club.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye: Hi, Timothy. Congratulations on the publication of The Titanic Survivors Book Club. I am amazed at how you recuperated the Titanic story and turned it into a material of fictional delight. What inspired this imagination that a shared love of adventure and books can hold together the disparate lives of anguished survivors of the shipwreck?

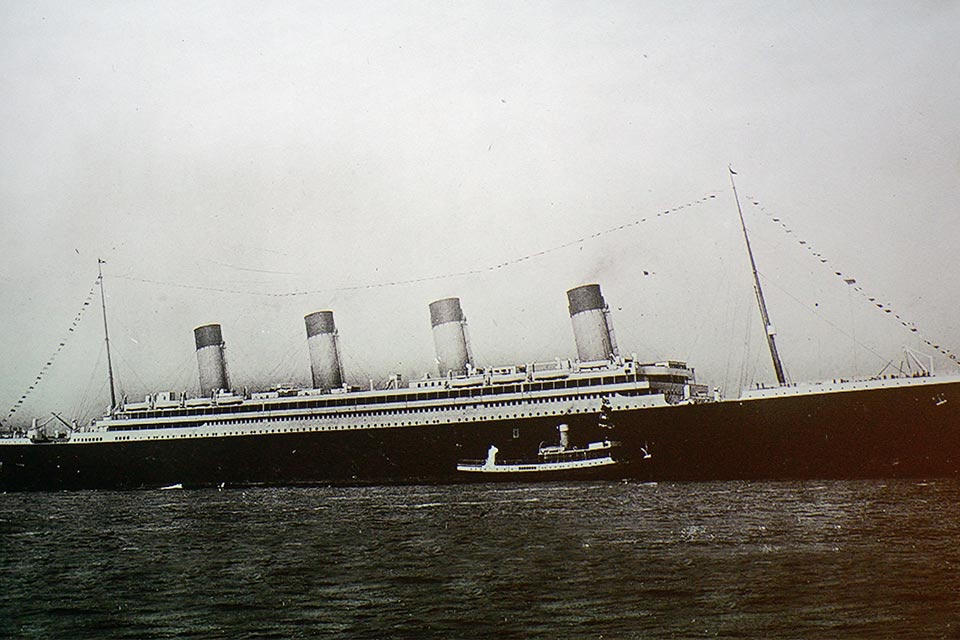

Timothy Schaffert: The sinking of the Titanic is something so embedded in American culture, I feel somehow that I’ve always been aware of it. I remember reading a historical novel set on the Titanic when I was in high school. It was one of those paperbacks you would find for sale on a rack in the checkout lane of the grocery store. I can’t recall the title. I think it was simply The Titanic. I don’t think I’ve ever been tempted to write anything set on the ship, but I was interested in reflecting on our fascination with its sinking. For a long time, I worked on a novel about a filmmaker in the silent era who builds a replica of the Titanic in the California desert.

I eventually abandoned it, but some years later, I imagined ways to revive the idea. Instead of viewing the Titanic through the eyes of a megalomaniacal moviemaker, I settled on a humble, lovelorn Parisian bookseller. The book club aspect, however, was suggested by my editor as we discussed my ideas for my next book. We came up with the title almost instantly after that suggestion, and the novel bloomed from that. The narrator emerged from my research into the history of bookselling in Paris and from the books I imagined he would read and recommend. The tragedy of the Titanic—and our sense of the ship’s opulence, and all the dimensions of fate—has been a connective thread for communities of aficionados since the ship’s sinking, so I delighted in exploring such a community that had some urgent business to settle with that sunken ship.

Darlington: Throughout the days I read your novel, I sometimes paused from doing a chore to wonder about the trajectories of your characters: evangelist Henry Dew missed the Titanic because he “couldn’t bear to leave the spa shop in Cherbourg, where [he] wiled away hours soaking in sulfur bath while sipping pink wine”; actress Delphine Blanchet’s fear of losing her voice from making her first silent film made her miss the Titanic; physician and lecturer Jules Beaufort did not board the Titanic because he preferred the Olympic where he would see the ship’s stenographer whom he was beholden to; and Rémy Leroy, the gambler, was saved by his sexual partner who protested his traveling with the Titanic. This is amazing or would have been so if the Titanic wasn’t such a ghost that follows its survivors about. I was moved by Yorick’s confession of the finality of the Titanic tragedy: “People who lived died, people who died lived . . . Once you’ve seen a night so dark, do you ever see day light again?” Why are we still ruined by the things we survived?

Timothy: I think I was a morbid child, always fretting about some inevitability of an early demise. I was kind of sickly, and I’d had a rather awful, brain-damaging fall as a toddler—off a set of bleachers head-first onto cement—so all of that instilled a low buzz of fatalism. But, as it turns out, I’ve been very lucky, and I’ve survived my life so far. I’ve had a few other accidents along the way that could have potentially taken me out, as have many of us. And some of us to a much larger degree, of course. People who live through a war, for example, have a radically different sense of survival than I do, a sense of grief and fear that I can’t fathom. I think such things leave us standing at the precipice of existence and perhaps of reality itself.

Yorick, my narrator, grows up in a theater, his father a Shakespearean actor, and his dearest friend and mentor a set designer, and that greatly shapes his sense of luck and survival. He interprets his life not as random happenings but as a narrative arc. He can imagine himself more as a character than as a man, which is inspired also by his covert sexuality that leaves him feeling somewhat removed from the conventions of society. For many of us, tragedy looks like chaos and disorder, while survival feels like a glimpse into order and meaning, and that little glimpse can be maddeningly tantalizing.

Darlington: And to think that the Titanic isn’t done taking lives! How did you feel when you realized on completing the novel that another Titanic tragedy had happened?

Timothy: In our search for order out of chaos, we’re comforted somehow by the thought of the Titanic as cursed. While a curse might be terrifying when you’re under its spell, it’s a sort of a blessing to us on the other side of it. It hints at magic and wonder and something that brings definition to the indefinable. The tragedy of the submersible is also a cautionary tale. They were all tempting fate in a manner that would seem careless under any circumstances, but especially considering that it centered on such a notorious disaster. They would have been pressing their luck, even if the conditions had been in their favor. And the fact that the submersible wasn’t even guaranteed to provide much of a glimpse of the wreckage, or even necessarily get anywhere near it, spoke to a daredevilry that doesn’t evoke much sympathy. We love the Titanic story for its heroes and its victims, and the submersible story seems to fly in the face of all that, and wantonly so.

We love the Titanic story for its heroes and its victims.

Darlington: It is fascinating how love is at the center of a novel that captures the triumphant tragedy of a precarious world. Yorick, your narrator, is endeared to the photographer Haze, whose beauty he considers queer and charming. But as a closeted gay man, there’s only so much Yorick can do about his feelings. And Haze’s courting of Zinnia’s attention makes Yorick’s situation more complicated. The triangle of love, desire, and repression can be haunting. It is already over a century since the Titanic sailed and sank. It was a time when the world allowed men like Yorick no space, or just a little space, to express their sensual and sexual desires. What would have become of Yorick and Haze if they lived in this present time?

Timothy: Unrequited love is timeless, of course. I only just recently learned about the concept of “limerence.” Well, I’ve always been aware of the concept, but I’ve only just learned the word, which I’ve seen defined as a “state of mind” rather than a “condition” or some other pathologizing term, but it is nonetheless something that psychologists use in their diagnoses of patients. You’re experiencing limerence if you’re preoccupied with someone who is an unlikely romantic possibility. In other words, it’s a debilitating infatuation with someone who’s just not that into you. There are support groups and Facebook pages devoted to it, and people post about their emotional turmoil and the objects of their affection.

I suspect, historically, that limerence has been central to the homosexual experience for generations. Young queer people, especially, might tend to fall for people who enjoy their attention but might not be queer themselves, or might be experimenting, or might be closeted. All the dimensions of sexuality are more vast than mere identity, so in the pre-identity world of Yorick and Haze, they succumb to their hearts in the same way we do now but would perhaps not have the same words for situating their desire.

I suspect, historically, that limerence has been central to the homosexual experience for generations.

Darlington: I admire the relative equanimity with which the toymaker took the loss of his wife on the Titanic, as he narrated to other members of the book club: “I nearly left without her. And when the ship sank, it went topsy-turvy. I questioned all logic. Perhaps all those years of her sadness was . . . premonition. All those aches and pains she complained of . . . maybe they were just . . . rehearsal. And then came that day, the day the Titanic left the dock, that she rescued us with her despair.” It sometimes happens that we know a certain pain and every other pain we had known before suddenly becomes endurable when compared to it. It seems the past was preparing this character for a future of deeper tragedy. How did you feel listening to this expression of grief?

Timothy: All the members of the Titanic book society have opportunities to explain themselves throughout; and this informed the books that I selected for the club discussions. This was a very unusual way to write a novel. While any novel is indeed a constructed thing, this one felt even more so, as I was in the narrator’s role of identifying books that might provoke the other survivors. And the discussion itself shouldn’t alienate the reader. I wanted it to be meaningful to the readers of my book even if they hadn’t read the books up for discussion. So, the books needed to entice the characters into expressing their grief, their longing, their expectations.

Darlington: The literary opinions your characters offer in the book club are enlightening. I suppose the intertextual quality of the novel sheds light on your training and experience in literary scholarship.

Timothy: I ended up with long lists of possibilities for books to include, and it was a little despairing to have to abandon some of the selections, in the name of brevity. While I did draw somewhat from my own study (The Awakening is one of my favorite books of all time, and I’ve been teaching The Picture of Dorian Gray for years), I also learned a great deal about books I’d not read before. And since I had to position those books specifically in 1913, I was inclined to learn more about the perspectives of the books at that time, and the editions available, which was a satisfying and rich experience of window shopping the online rare book dealers, and even visiting our own rare books in the collections of Love Library at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. This led also to discovering the role of publishing and bookbinding in shaping our sense of the literary culture we have today.

Darlington: Yorick’s love of bookbinding is remarkable. What inspired his vocation? What does he represent in a world in which books are banned, destroyed, and abandoned without care?

Timothy: Yorick’s fascination is inspired by my own preoccupation with books as objects, which has been a topic for my writing classes for years. We examine the role of typography and design in how we tell our stories, and we consider the possibilities for innovation. We look at works like B. S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates, which is a novel in a box, each chapter to be plucked out at random. Or Lily Hoang’s Changing, a novel in the form of the I Ching. Or poetry by Tyehimba Jess and Anne Carson and Emily Dickinson, for which even the paper it’s written on becomes part of the telling. As for what Yorick might represent today, in terms of his relationship to books: he speaks to a legacy that continues to impassion booksellers, and authors, and editors, and publishers, a devotion to literature and history and information and the word itself, and the book as this magnificent vehicle of conveyance, both practical and artful.

Yorick’s fascination is inspired by my own preoccupation with books as objects, which has been a topic for my writing classes for years.

Darlington: Speaking of art, I like your description of Zinnia’s signature, “an extravagance of curlicue and spin, the Z of it especially dizzying.” I pay attention to signatures. I spent years creating one and mastering it. The first time I went to open a bank account in Nigeria, the accountant, who was thrilled by my signature, looked up from her computer and asked me: “Enyi m, are you a millionaire? You have the signature of a multimillionaire.” I laughed, especially because she called me “my friend.” See, Timothy, I sometimes consider a signature a reflection of human personality. Do signatures remind you of anything, as an author, as a person?

Darlington: Speaking of art, I like your description of Zinnia’s signature, “an extravagance of curlicue and spin, the Z of it especially dizzying.” I pay attention to signatures. I spent years creating one and mastering it. The first time I went to open a bank account in Nigeria, the accountant, who was thrilled by my signature, looked up from her computer and asked me: “Enyi m, are you a millionaire? You have the signature of a multimillionaire.” I laughed, especially because she called me “my friend.” See, Timothy, I sometimes consider a signature a reflection of human personality. Do signatures remind you of anything, as an author, as a person?

Timothy: When you write about history, you spend a fair amount of time examining documents and old conventions of communication; handwriting is spectacularly fascinating, especially considering our current age when penmanship is fading away or, perhaps, has faded away completely. As you indicated, it’s been a mode of expression for generations. And I’m fascinated too by typography and page design, and all the extraliterary elements that go into the publishing of a story, some of which is also at risk in an age of easy-access audio and podcasts. But in terms of signatures specifically: I’m disappointed to see a book that’s been signed by its author and that signature is nothing but a loop, or a line. I suppose if you’re an author who attracts hundreds to your signings, such minimalism is necessary to prevent your hand from cramping. But the book is worth more to me if the author’s signature shows some flourish and flair. A signature should enunciate!

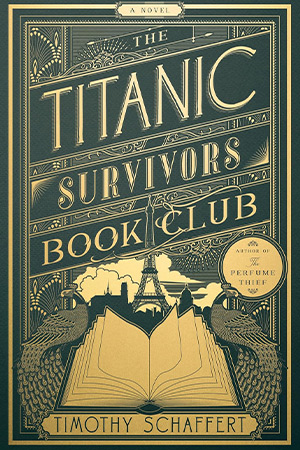

Darlington: The emblem of the Titanic Survivors Book Club is charming. Two peacocks resting at the two sides of an open book. What inspired it?

Timothy: The ship took with it a bejeweled edition of Omar Khayyam’s Rubaiyat, as it was being delivered to an American collector. On the cover were peacocks in gold thread. Because I was writing toward a deadline, I turned in early pages to my editor, and my editor passed them along to the designers, and I mentioned that Rubaiyat at the beginning of the novel. The designer then incorporated those peacocks into the cover image. I had the cover long before I turned in the final version. So that cover ended up influencing further content of the book; as a result, as I continued writing and revising, I referenced those peacocks more than I might have otherwise.

April 2024

Timothy Schaffert is the author of seven novels, including The Perfume Thief. His work has been recommended by the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Washington Post, Oprah.com, People, NPR, NBC New York, and other media. He is the Adele Hall Professor of English at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and co-editor of Zero Street Fiction.