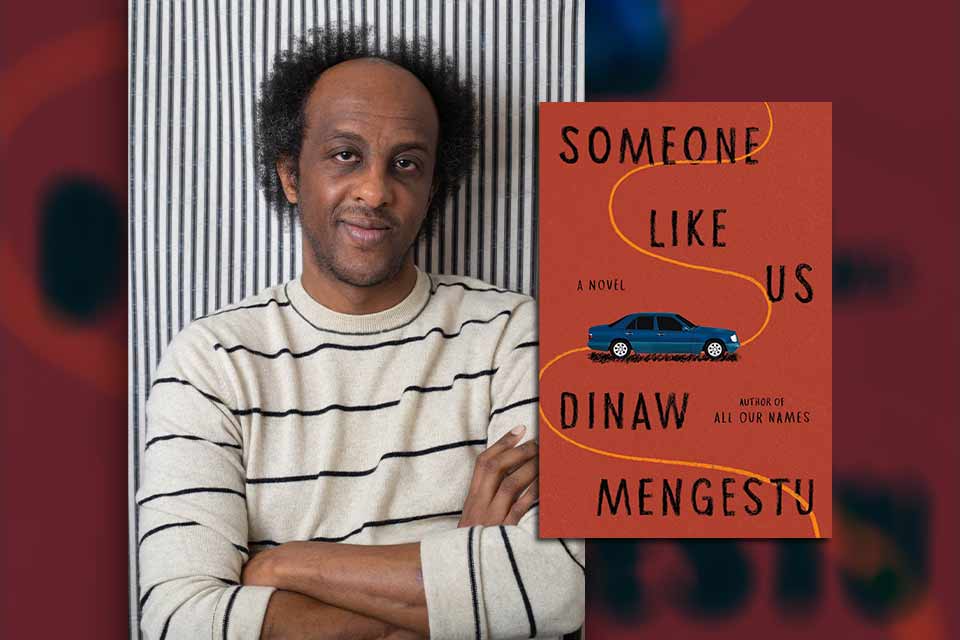

Doubt and Interpretation in Someone Like Us: A Conversation with Dinaw Mengestu

The facts of Dinaw Mengestu’s biography hardly break the surface of the writer’s vision of what it means to be in a place but not of it. In a 2024 Time magazine essay, Mengestu describes himself as “a writer whose work is rooted in stories of asylum” and decries the “damning and obviously racist narrative”—the dominant narrative—of immigration to the US. He calls for different stories that “consider what our borders might look like if we saw them as an integral part of our country rather than the end.” From its opening line (“I learned of Samuel’s death two days before Christmas”) of his latest novel, Someone Like Us draws the reader into the encircling stories of Mamush—a journalist living in Paris who embarks on a circuitous journey, in grief, to his Ethiopian community in DC—and of Samuel, a cab driver, dreamer, would-be writer, and Mamush’s unacknowledged father. In this brilliant novel, both mystery and meditation, Mengestu challenges that dominant narrative with a multiplicity of stories which make it impossible for us to look away. (The following conversation was conducted via Zoom.)

Renee Shea: Your first three novels were written within a few years of one another: 2007, 2010, 2014. But it’s been ten years until this one. Why so long?

Dinaw Mengestu: Some of it was that the book itself had a slow evolution and gestation, and it changed intellectually and conceptually as I was writing it. Some of the questions that I had thought about in the past—but hadn’t really figured out—began to take on a greater presence and energy just because of the time I’d spent thinking about them. Questions of ethics and representation, which are very closely related to what I teach, began to work their way into the text itself. Issues of my own role as author inside the narrative and what that role means—the implications of being the author, and trying to acknowledge my presence in the story without allowing it to take over—made the writing slower but also really beneficial.

Questions of ethics and representation, which are very closely related to what I teach, began to work their way into the text itself.

One of the benefits of time is that it allowed the story to grow in complicated and unexpected ways. It made me linger inside certain scenes and moments. Rewriting them many, many times let me see how the novel worked internally in ways that I don’t think I’d ever done before. With the other books, you begin them, get lost inside of them, write them—and you’re very happy to complete them. But in this one, there were these questions that were so much about what it meant to write and what it means to tell stories. Many times I thought the book probably wouldn’t work. Other times I thought I was done and then realized that no, actually I didn’t get it right, and I needed to go back and take it apart again. That process alone added at least a couple of years.

Shea: You’ve talked about this fourth novel being the closest to your first novel, The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears. It’s not just a recurring character; you’ve said you’re also critiquing your younger writer self.

Mengestu: In part, that’s because I was still learning what it meant to write. The first novel skirts around the Ethiopian diaspora community in the DC area. But I think I was not yet fully ready for that topic. Even in its earliest stages, I wanted Someone Like Us to be deeply rooted inside the evolution of that community. The novel is not just about seeing that community in one moment in time but over the course of an entire generation. Looking more deeply into that world is the heart of this story, and in many ways this is the community that I wanted to reach out to the most.

Shea: Near the novel’s end, Mamush refers to the “most important lesson” that Samuel tried to teach him: “everything was subject to doubt and uncertainty.” I wonder if this slippery quality is what led reviewers to describe Someone Like Us as “aggressively meditative,” “requiring the reader to live in uncertainty, to find any truths obliquely, if at all”? Do these descriptions ring true?

Mengestu: In some ways, they’re quite apt. Even when I don’t intend it, there seems to be an undercurrent of absence, of longing, of particular kinds of melancholy that sit under the circumstances in all my books. But it’s not that the book intends to be oblique in any way; it wants to be in dialogue with the reader. At an event someone asked me, Were you thinking about the reader as you wrote? Normally I would have said no, I don’t really think about the reader. But in this case, I very much thought about the reader as an active participant in making meaning inside of the text. That meant I had to make sure there was a text that invites you to engage with it, to sit inside the stories and find those with the most resonance, without feeling that any one story is going to define the characters in any specific way—but leaving that work up to the reader.

Shea: One of the most striking dimensions of the novel is the storytelling: the many different narratives or stories the characters tell about themselves—the lies, pretenses, inventions, and reinventions, sometimes wholesale fabrications such as Mamush’s false identity as Christopher T. Williams. You’ve said that which story a character chooses to tell and how they tell it is key to their identity. Part of that reality, especially for Samuel and Mamush, has less to do with who’s telling the story and more with the person receiving the story, someone who likely has a set of expectations for the “answer.” From a writer’s perspective, how does that work?

Mengestu: Maybe for some people that’s frustrating, but for me, one of the most important things is that the characters aren’t defined in the kind of totalizing way that makes you feel like, “Oh, I get it.” Because if you do, then I’ve done something wrong. At the end of the day, we’re just more complicated than that. So, the novel only seemed to work if there were lots of stories circling around each other and creating their own solidity by sheer volume. If there are only one or two stories that might not be real, it begins to feel like the characters are just distrustful. But if the characters are constantly inventing and telling stories—some of which are real, some of which may not be—then there are various degrees of truth. All [of the stories] together are essential to who the characters are. They all tell us something about how the characters live in the world and, sometimes, how they fail to live in the world.

“I was still standing in the middle of Samuel and Elsa’s bedroom, thinking about what Samuel would have wanted me to say to Elsa about his death, when Hannah texted me a photograph of an apple cut perfectly in half and laid to rest in the center of our coffee table.” —Dinaw Mengestu, Someone Like Us

Shea: You’ve cited the powerful influence of Susan Sontag’s book Regarding the Pain of Others. In fact, this novel’s title is taken from it: “The exhibition in photographs of cruelties inflicted on those with darker complexions in exotic countries continues this offering, oblivious to the considerations that deter such displays of our own victims of violence; for the other, even when not an enemy, is regarded only as someone to be seen, not someone like us who also sees.” Could you explain more about how Sontag’s analysis informs your sense of narrative in this novel, including Sontag’s idea of what something is “like”?

Mengestu: [For me, the question is] what does it mean to represent suffering and violence and other people’s experiences, when as the author or the person on the other side of that, you are inevitably just watching it? When you are looking at an image, whether the thing depicted is happening in real time or is even imagined, the tendency is to represent the thing in a way that allows somebody else to look at or read it, and then feel like they’ve understood what happened. That comes at a particular cost and risk. Sontag does a beautiful job of explicating that through photography.

As she notes, when we make images, we have to assume that we can know who the viewers are, because we are imagining their interpretation—and thus construct a “we.” We are here and that thing that happened is over there. Doing so allows us to look at the event from a distance, as spectators. But doing so also creates a problem, because it separates us from the experience and allows us to remain somewhat immune to it. One of the things that the “something like” does is to move away from a singular representation toward something that demands multiple ways of understanding it, multiple ways of representing it, in order to approximate a version of what happened. That multitude [of possible interpretations] does something to us as the spectators: we are no longer able to just watch it, or say, I saw it, and I understand it, because now we’re charged with looking at it again and again and again.

The “something like” moves away from a singular representation toward something that demands multiple ways of understanding it.

There’s something similar in the characters in Someone Like Us and the multiple stories that they tell. If the reader doesn’t like that, there’s space to walk away—to a certain degree. But if the reader stays with that multiplicity and engages it in multiple ways, then the multiplicity itself is the thing closest to what actually happened. It’s the thing that implicates us, as spectators, because we have to put in the work and look at it again and again and again until the idea of the separation between us and the object of our observation begins to collapse—not in the sense that we’re inside of it, but in that our relationship to it is under interrogation.

Shea: The nine photographs interspersed throughout the novel are haunting in and of themselves, but you’ve said they also form their own story arc. They were taken by your wife, who is a photographer, as is Mamush’s partner Hannah. Could you talk about how these images work as another narrative and also how they came about?

Mengestu: I remember the very first time I tried playing with the idea of what the photographs could do and thinking about the images together, and I hadn’t told my wife that I was doing it yet. Certainly that was coming from thinking a lot about photography, because of my wife and her work, but also from reading Sontag. The first time I kind of dropped an image that she’d taken into the manuscript while I was working on it, I liked the way it worked on the page, but I also liked the way it gave her a kind of autonomy in the novel, different than anything I could do on my own. For a while, I thought maybe that one photograph would be it, or maybe there’d be another photograph. But after the first draft was completed, I realized that the way Hannah communicates through images, especially to Mamush, is very particular. Her communication is its own discourse with its own vocabulary, a way of trying to get him to see something that he might not be able to recognize. Oftentimes these gestures express a kind of love he might not be fully witness to.

Once that became really clear, I asked my wife to take the photographs. I gave her some of the text and the pages where I wanted the images to go. I asked her to take them, but I told her that however she wanted to interpret what was inside of the text, however she wanted to respond, was entirely up to her. It was important that I not say anything about that at all. I tried to say very little when she would show me different versions, even if I preferred one version or the other, because I felt like it was necessary that I not be in control of the images, that there be a secondary perspective in the story independent of my own but still in conversation with the novel or with me. She would construct these scenes, and we would build them up together as she did different drafts and versions. We found these wonderful echoes happening in the text that weren’t even planned. That matching of text with image—no, it’s not matching—that interaction between image and text is really nice.

Shea: If there is one word that captures the essence of the novel, I think I’d go for “restless.” Some characters are restless to achieve bigger homes, more of whatever the American Dream is. But isn’t there a deeper psychological restlessness that defies the trope of the immigrant experience? Samuel and Mamush are always in motion—going from one place to the next, shuttling from cab to cab. In fact, Samuel’s American Dream is in motion: “building a business that stretched from D.C. to California, one that operated by word of mouth and that catered exclusively to . . . immigrants, migrants, refugees, anyone who was in the wrong place and needed to be somewhere else but didn’t know how to get there.” Does this restlessness come from anxiety, paranoia, displacement?

Mengestu: I’d say all of the above. For some, it’s that they are where they are but not necessarily where they would like to be. This is where you are, and it’s not where you imagined or expected you would be, but this is what life has done with you. It’s not such a bad place, just not the place you consider yourself to be inside. Sometimes people are born and raised in an area they know, and it feels like home, an anchored space for them. But other experiences make that feeling hard, if not impossible. There’s a certain restlessness that comes just from what you have. Another restlessness comes from ambitions and ideas that you have that aren’t going to be realized—in part because of where you are, where you ended up, and when the opportunities you might have had no longer present themselves to you—and coming to terms with that.

Shea: I’m intrigued by how you handle time in the novel. The constant motion is not only geographical. Mamush realizes that the very concept of time is arbitrary, because nothing is certain or fixed. In terms of the novel, which takes place over three days, that means constant movement between past, present, and, ultimately, an imaginary future. Sometimes when I’m reading a paragraph, I hardly even realize that I’ve shifted from one time frame to another, but it’s so beautifully done that I feel it’s exactly what I need—not to understand, but simply to be with the characters. How did you keep track through writing, planning, and revising?

Mengestu: I think that’s a lovely way to express it: the idea of wanting to be with them—the feeling of being carried away with them. Maybe, if you don’t know everything about them, you get a different type of proximity. I think that feeling of having moved through these interior states that float in and out of time is the way we remember things.

I wanted to start a sentence in spring and end in December—to feel like I could carry a person through all these layers of their past in one motion.

Psychologically, we sort of move in and out of time quite fluidly, so I wondered what it meant to reflect that. I remember the first time writing it felt like testing how elastic a page or paragraph or chapter could be. It’s that sense of not being in the right place—displaced physically, emotionally, temporally—what it meant to start a story with one scene and then move to another and through another. I remember even a year or so before I started writing, I had this character in my head, and I wanted to start a sentence in spring and end in December—to feel like I could carry a person through all these layers of their past in one motion.

I think the novel grew into that feeling, and as I grew comfortable in that mode, it increasingly became possible to sustain it. I could put myself into a memory and allow that memory the space to flow, sometimes one memory flowing into another. I think the craft itself was a matter of time: the time it was taking to write these scenes, not to get them right on the first try, but to rewrite them and then try to figure out how I could keep opening them up to more and other possibilities.

Shea: The constant physical and geographical movement of Samuel and Mamush—across time and place, continents and cultures—dramatically contrasts with the stillness of Hannah and their young son. In one passage, Mamush observes the two of them sitting on the bed together, leaves for a short while, comes back, and says nothing happened between the time he left and returned. Hannah takes him to task: “That’s the American in you talking. You think everything has to be different in order to change. You come back, and you think: Nothing has moved. Everything is the same. But that isn’t true. So many things are different with us. You just can’t see them.” Is that stillness something Mamush has to learn about, or am I reading too much into it?

Mengestu: No, I think you’re right. What she’s trying to tell him is to look carefully at the world in front of him and he’ll find so much more there than he might be able to see because he’s not settled. That sort of unsettled nature means a person fails to see the complexity of layers—a found sort of love and beauty that exists in the world right before him. Things might be still in a certain sense, but she’s saying that this stillness that he imagines isn’t stillness; there’s a whole undercurrent of intimacy and love that he is unable to see, though it’s not because he doesn’t want it. There is a way to give love, but it’s equally important to receive it. And he hasn’t figured out the second part yet.

Some of what I think Hannah’s doing with the photos is saying, You don’t know what you have because you’re not seeing it fully. You’re only noticing the first layer, and you haven’t learned how to look beyond that superficial layer into all the things underneath.

Shea: Samuel is Mamush’s guide, the one who asks him to ask himself. He posits questions and waits for Mamush to respond, yet Mamush never seems to entirely comprehend the questions. Will he ever realize why Hannah and Samuel have been in constant communication to bring him to the same point, which boils down to family as home? In other words, is Mamush ever going to be okay?

Mengestu: I think so. That’s where he lands at the end; it’s why he’s going to go back home. If he wasn’t going to go back, there would be a very hard future for him. But in the end, he is in the process of stitching together these different pieces of his life and recognizing where he needs to be. Out of all the scattered parts of his identity, the one space that is core is home. He recognizes that the one thing, the one space where he can actually be rooted, is with his wife and son.

Shea: And so the stillness is family?

Mengestu: It’s where he might—might—be able to be still.

November 2024

A native of Ethiopia, Dinaw Mengestu is the author of four award-winning novels: The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears (2007), How to Read the Air (2010), All Our Names (2014), and most recently Someone Like Us (2024), all named New York Times Notable Books. As a freelance journalist, Mengestu has written about Darfur, northern Uganda, and eastern Congo. A MacArthur and Guggenheim Fellow, in 2016 he joined the faculty of Bard College, where he is the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Professor of the Humanities and founding director of the Center for Ethics in Writing.

A native of Ethiopia, Dinaw Mengestu is the author of four award-winning novels: The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears (2007), How to Read the Air (2010), All Our Names (2014), and most recently Someone Like Us (2024), all named New York Times Notable Books. As a freelance journalist, Mengestu has written about Darfur, northern Uganda, and eastern Congo. A MacArthur and Guggenheim Fellow, in 2016 he joined the faculty of Bard College, where he is the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Professor of the Humanities and founding director of the Center for Ethics in Writing.