Introduction: Black Reparations and Restorative Justice

Santa Monica, California, has long promoted itself as an affluent resort community and tourist hotspot. The seaside town in Los Angeles County is best known today for its amusement park on the Santa Monica Pier, its sun-soaked boardwalk, and the tanned surfers and bodybuilders who frequent the outdoor gym known as Original Muscle Beach. Earlier in its history, however, it was one of the most ethnically and racially diverse parts of Greater Los Angeles, home to several thriving Black communities.

I first visited Santa Monica in the early 2000s, and I have been back multiple times since then for family vacations. Yet I was clueless about the city’s Black history until 2022, when I stumbled upon an inconspicuous historical marker for “The Inkwell,” memorializing the small stretch of Santa Monica Beach where Blacks were able to gather in relative safety during the Jim Crow period (1900–1970). The City of Santa Monica installed the commemorative landmark in 2019.

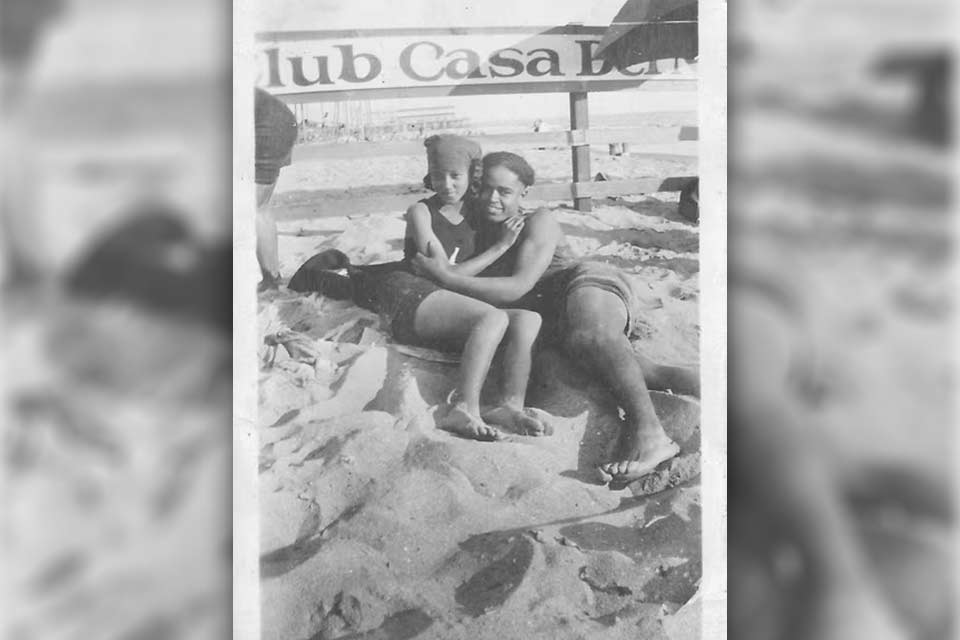

Whites in Santa Monica had disparagingly dubbed the site “The Inkwell,” a racial epithet that was used in other parts of the country as well. Among the Black community, the 200-foot partitioned-off area was affectionately known as the Bay Street Beach. The wording on the plaque only alludes to the systemic prejudice that led to the exclusion of Blacks from Southern California beaches. Interestingly, it also mentions the pioneering Black Latino surfer Nick Gabaldón, who awed Black and white beachgoers from Santa Monica to Malibu with his surfing prowess.

The Inkwell marker exploded what I thought I knew about Santa Monica. Suddenly, I was both intrigued to learn more and perplexed that I did not know more already about how Black people had helped form and sustain community in this unique waterfront city. Over the decades, Blacks in Santa Monica faced constant attempts to displace or exclude them. In 1922, for example, two Black investors sought to build a beach club on Ocean Drive, where the luxurious Shutters on the Beach Hotel is currently located. To the businessmen’s dismay, city leaders refused to issue them a building permit. The property holder subsequently sold the land to the Shutters investors, and the new white owners were quickly granted a permit to build a hotel, which opened in 1924 and has operated continuously ever since. As this example suggests, overt city-sanctioned racism stymied Black access to property ownership and wealth creation in Santa Monica.

Due to systemic housing discrimination throughout the Los Angeles area, Blacks were forced to live and build businesses in multiple overlapping enclaves on Santa Monica’s geographic and economic periphery. During the 1920s, the Black community was concentrated mainly within the Belmar Triangle and Broadway neighborhoods along Pico Boulevard, the major thoroughfare connecting Santa Monica to downtown LA. Home to restaurants, meeting halls, churches, and a variety of entertainment establishments, Broadway and Belmar flourished despite the pervasiveness of racial prejudice.

During the urban-renewal campaigns of the mid-twentieth century, Santa Monica’s predominantly Black neighborhoods were targeted for demolition. In the 1950s, city leaders utilized the construction of a new civic auditorium to displace Black and brown businesses and homes within the Belmar Triangle. On a wider scale, large swaths of the Broadway neighborhood were razed to make way for the Santa Monica Freeway. According to the Los Angeles Times, 550 Black families were displaced through eviction when eminent domain was exercised to seize property for the new section of interstate. The original demolition zone included the Phillips Chapel Christian Methodist Episcopal Church, a symbol of the Broadway community and the Black community’s first and oldest institution, but it was spared by city leaders after extensive community protest.

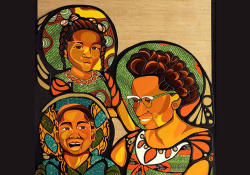

I conducted four interviews for this Bearing Witness section to glean more information about Black history and Black life in Santa Monica. The first two interviews highlight remembrances of Black Santa Monica during its founding years and later during its heyday in the 1950s. Leana Brunson McClain and Carolyne Edwards, who spent their childhoods in Santa Monica, recall the historic Broadway neighborhood as a haven for the city’s Black, Mexican, and immigrant communities. Separately they have organized multiple community projects to preserve this history for future generations. In my interviews with them, they discuss those community remembrance projects and their intended impacts.

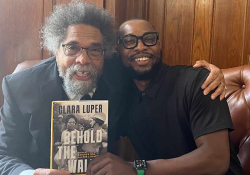

The other two interviews probe the relationship between remembrance and repair. I discuss with civil rights attorney and activist Areva Martin the Section 14 case in v, which involved a historic reparations settlement in compensation for decades of discrimination against the city’s Black residents. In my final interview, I dialogue with University of California Los Angeles professor Marcus Hunter about his new book, Radical Reparations, which makes a bold case for how reparations for slavery and historical anti-Black discrimination can lead to contemporary societal flourishing.

I have been inspired by what I have learned about the history of Black community-building in Santa Monica and greater Los Angeles and the testament it offers to resilience. I hope the four interviews presented here offer collective evidence that bearing witness can serve as a profound form of resistance to historical and contemporary racism.

University of Oklahoma