Clara Luper, Freedom’s Classroom, and the Civil Rights Movement: A Conversation with Marilyn Luper Hildreth

Bearing Witness: In his ongoing column, which appears in every other issue, Karlos K. Hill highlights the efforts of cultural figures doing works of essential good around issues of social justice.

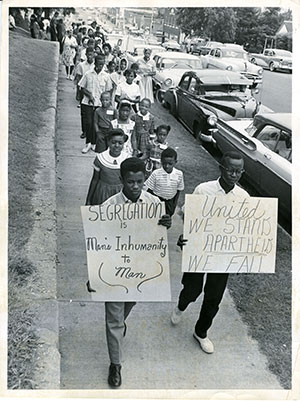

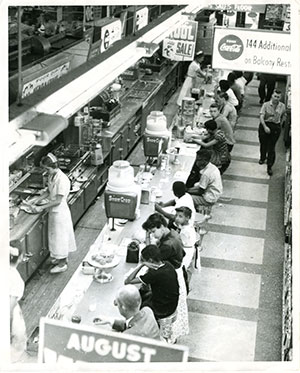

On August 19, 1958, a high school history teacher named Clara Luper and thirteen members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Youth Council, ranging in age from seven to fifteen, organized a sit-in at a segregated Katz Drug Store in downtown Oklahoma City. Within two days, the Katz Drug Company had desegregated not just this one local store but more than fifty locations in states across the Midwest. One of the first sit-ins of the civil rights movement, this peaceful protest by a small group of young activists would galvanize future demonstrators in Oklahoma City and throughout the nation.

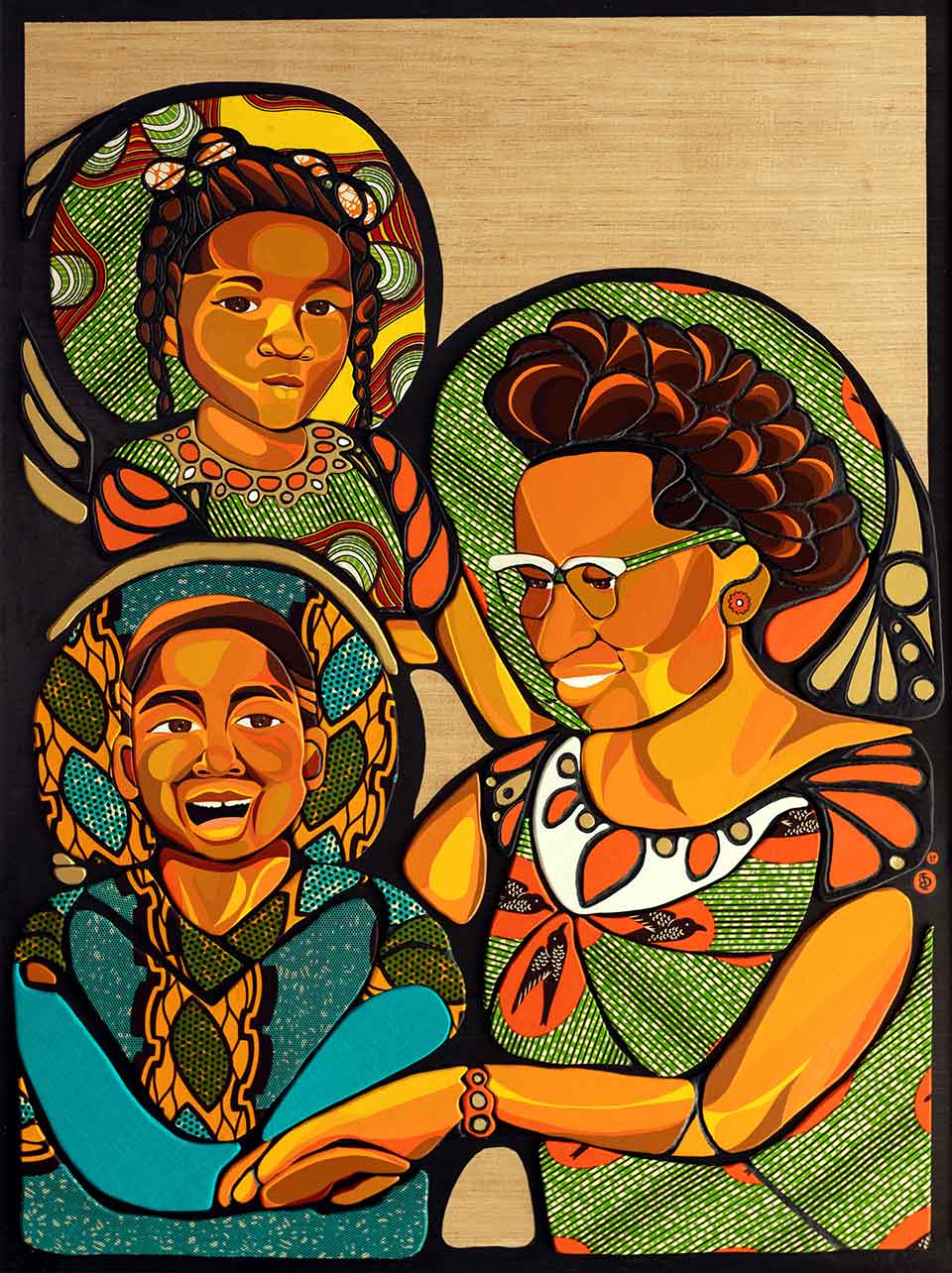

Over the next six years, Clara Luper and her students organized sit-ins, lay-ins, and boycotts that would eventually lead to the desegregation of white downtown stores and restaurants in advance of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. By courageously fighting against injustice while simultaneously centering youth activism, Luper created an enduring legacy of nurturing social change through nonviolent civil disobedience.

Clara Luper passed away in June 2011. On May 3, 2023, she would have turned one hundred years old. Additionally, August 19, 2023, will mark the sixty-fifth anniversary of the historic Katz Drug Store sit-in. In anticipation of these upcoming commemorations, I talked with Clara Luper’s daughter, Marilyn Luper Hildreth, who participated in the Katz Drug Store sit-in, to help me understand its significance.

Karlos Hill: To start with a simple question, can you explain to readers who Clara Luper was to you?

Marilyn Luper Hildreth: Clara Luper was my mother. And not only was she my mother, but she was a mother to many other children, both in our community and in our society. She would always make room for another child. Mom was a teacher before she became the Youth Council adviser, and she was really popular with her students. She enjoyed creating experiences for young people that they otherwise could never have had, and that was especially true in the classroom. She had a way of bringing history alive in her classes.

For example, in order that they could better understand the functions of the government in Washington, DC, she had her students take part in mock elections, where they cast votes to elect fellow classmates as senators, members of the House of Representatives, and president. And for fifty years she took young people to the NAACP National Convention, including people who I call the “have-nots.” They did not have a lot of money and did not have a lot of things, but she wanted to give them that opportunity, because she was able to see things in young people that others overlooked.

She believed that all children can learn, so she had to find out how best to teach those young people in order to motivate them to be the best that they could be. She remembered every one of her students for the rest of her life. She had a real concern for them and felt deeply committed to them, and they felt the same way about her. They knew that she would always be honest with them. Even when she was correcting them, they knew that she was trying to help guide them in the right direction. She tried to bring out the best in everyone she dealt with.

Hill: Can you share a favorite story about your mother, perhaps a time when she helped to guide you in that same kind of way?

Luper Hildreth: Mom was always inviting people to dinner, and there was one time when she had asked some people to come for dinner and told us that we were having fried chicken. We always had enough food, but we lived frugally, and it was not every day that we got to have fried chicken. So Calvin and I got into an argument about how we were going to get our favorite piece of chicken off the plate before our guests got theirs. Mom heard us and said, “I can’t believe the two of you are arguing about that!” Our feelings were hurt because she was so disappointed in us for acting that way. So when we sat down to dinner, we said the blessing and then passed the chicken. And do you know what happened? Our guests turned out to be vegetarians! Here we’d been raising so much Cain about that chicken, and our visitors didn’t even want any. Calvin and I felt so bad that we ended up not eating any of it either.

Hill: So she was always teaching, even at the dinner table. What was the lesson that you think she wanted you to learn that day?

Luper Hildreth: She wanted us to think about things that have substance, to focus on things that really matter.

Mom wanted us to think about things that have substance, to focus on things that really matter.

Hill: Your mom had a special talent for empowering people. She believed that everybody has greatness in them; you just have to develop it, cultivate it, nurture it, and watch it grow. Having gotten to know some of her former students, I would say that her greatest legacy is the love that her students have for her to this day. I can see the deep love you all have for one another and the profound sense of camaraderie that you share.

It goes back so many years that it has made you a family. That kind of connection is something your mother cultivated. Her students could feel the love that she had for them and her unwavering commitment to them. And you all still live it and share it by remaining active in the community, working and advocating and pushing the conversation ever forward. I like to use the term “freedom’s classroom” in thinking about your mother’s legacy: her work as a teacher remains transformative because her students continue to have an impact.

Luper Hildreth: She would always say that no matter how much education you get, it can’t teach you how to treat people and get along with them. And if you don’t know how to relate to people, you don’t really know anything. She also believed that everybody has their own story, and you can never really know someone else’s motivation.

Hill: That is so true. We come from so many different places and are impacted by so many different things that we end up on different journeys. We may think that someone else is on a similar path to our own, but so often that’s not the case.

Luper Hildreth: And it wasn’t just the kids who looked to her as a leader. The community listened to her radio show for guidance. When they wanted to know whom to vote for, she would bring in the people who had come to our community wanting us to give them our votes, and she would ask them the hard questions that nobody else was asking. A lot of people did not want to be on her show because of that. If you made a decision that affected this community, you were going to have to come to us and explain why.

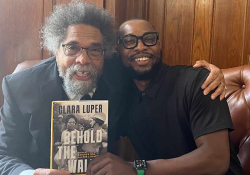

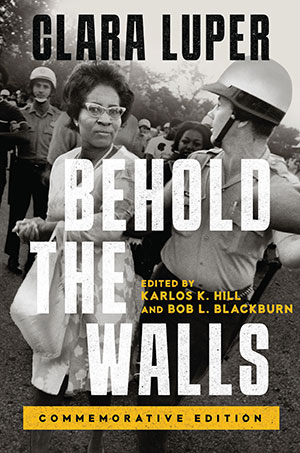

Hill: In 1979 your mother published a memoir of the movement in Oklahoma City, which she titled Behold the Walls. The book does a great job of giving readers a sense of what happened, why it happened, how it happened, and what it felt like when it happened. It also shows how integral children were to the movement. She goes into detail about why it was so necessary for her and the students to resist Jim Crow segregation, specifically the segregated lunch counters in downtown Oklahoma City. Is there anything you can tell me about your mother’s reasons for wanting to write Behold the Walls?

Hill: In 1979 your mother published a memoir of the movement in Oklahoma City, which she titled Behold the Walls. The book does a great job of giving readers a sense of what happened, why it happened, how it happened, and what it felt like when it happened. It also shows how integral children were to the movement. She goes into detail about why it was so necessary for her and the students to resist Jim Crow segregation, specifically the segregated lunch counters in downtown Oklahoma City. Is there anything you can tell me about your mother’s reasons for wanting to write Behold the Walls?

Luper Hildreth: I don’t know what motivated her to write it. All I know is that I looked up one day and she was working on the book. She had always kept a daily journal, and she was constantly taking notes. I can tell you something else about Mom that you don’t know: she read the Congressional Record every day. She was frequently ignored by both the white community and the Black community, but she would always say, “One day people are going to write about me.” I think she wanted her story to be told, and she wanted to tell it her way.

“Each of us must be a Joshua, Blowing our trumpet of Freedom’s Songs.” - Clara Luper, Behold the Walls!

Hill: With the upcoming republication of Behold the Walls, a whole new generation of readers will be introduced to this story that your mother wanted to share with the world, by reading it in her own words. What do you hope today’s audience will gain from the book?

Luper Hildreth: My mother wanted to have a voice, and she wanted others to understand why she did what she did. She wanted them to know about the courage and the dreams of the young people who took part in the sit-ins. She wanted people to know their names. Who could have imagined sixty-five years ago that a group of young people in this town would launch a movement that would end up changing the minds, the hopes, and the dreams of so many young people throughout this nation?

Hill: That is the radical faith of what you all did. It was never about you. It was never about your mother. It was always about something so much bigger: the struggle, and right versus wrong. She was never someone who tried to win popularity contests; she always lived in service to her students and to the movement. I would venture to say that your mother’s wealth can be measured in people—the number of people who knew her and loved her, the number of people she touched. If she were alive today, what words of encouragement do you think she would offer to those who are currently fighting both for peace and against injustice?

Hill: As someone who studies our Black radical political tradition, I view leaders like your mother as extremely bold. It wasn’t just that she loved people. It wasn’t just that she centered nonviolent civil disobedience. On top of all those other attributes that we’ve talked about, she had the kind of boldness and courage that scared people. Her willingness to go into that Katz Drug Store in 1958 with thirteen students—that was a bold move. And because she was willing to be bold, she encouraged others to be bold right along with her. She taught them how to be bold in a nonviolent way. That’s where so much of her power was, and still is. That is where her magic lay.

We must have faith, hope, and determination if we want the dreams of the civil rights movement to become a reality.

She truly lived a rich and amazing life. She was only thirty-five when she became the NAACP Youth Council mentor, and it was not long thereafter that you all began to make history. Having gotten to know her through you and some of her former students and colleagues, I can confidently call her a peer of Martin Luther King Jr., a peer of Malcolm X, a peer of Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker. Clara Luper stands tall alongside the other great civil rights leaders. If she was able to lead a small group of children in Oklahoma City in ways that changed the country as a whole, at a time when it was not always safe to be a Black child in America, then we should all strive to summon that same kind of strength to deal with our own challenges. Her teachings can provide the rest of us with a way to think about our own lives, and a model for how best to live them.

February 2023

Editorial note: The University of Oklahoma Press’s new edition of Behold the Walls is forthcoming in July 2023.

One of the late Clara Luper’s three children, Marilyn Luper Hildreth was one of the original thirteen children who participated in the first sit-in that took place at Oklahoma City’s Katz Drug Store. She currently serves on committees for the Clara Luper Sit-In Plaza, Clara Luper Legacy, and the Oklahoma Clara Luper Civil Rights Center, and spends her time giving motivational speeches and continuing her mother’s legacy.

One of the late Clara Luper’s three children, Marilyn Luper Hildreth was one of the original thirteen children who participated in the first sit-in that took place at Oklahoma City’s Katz Drug Store. She currently serves on committees for the Clara Luper Sit-In Plaza, Clara Luper Legacy, and the Oklahoma Clara Luper Civil Rights Center, and spends her time giving motivational speeches and continuing her mother’s legacy.