The Keepers of the Books

Where have books been? Where are they going? In this tour d’horizon, Alice-Catherine Carls finds common goals among keepers of books even as the many forms of the book expand.

I generally distrust social media, but scrolling through the pages of Instagram offers unexpected musings. Between royalty displays, daredevil feats, and wildlife postings, opulent and dilapidated interiors of castles and villas remind us of the vanity of all things. The photographs of French designer-turned-advertiser Francis Meslet show abandoned libraries while others showcase stately British libraries. Surfing the internet further reveals hundreds of pictures of dilapidated or abandoned libraries and entire warehouses filled with discarded books. Fortunately, throughout history, for every book destroyed, one has been saved, and for every intentional or nonintentional, commercial or accidental destruction of books, there has been a loving devotion to preserve the written word. We must never lose sight of this cycle of book production and destruction.

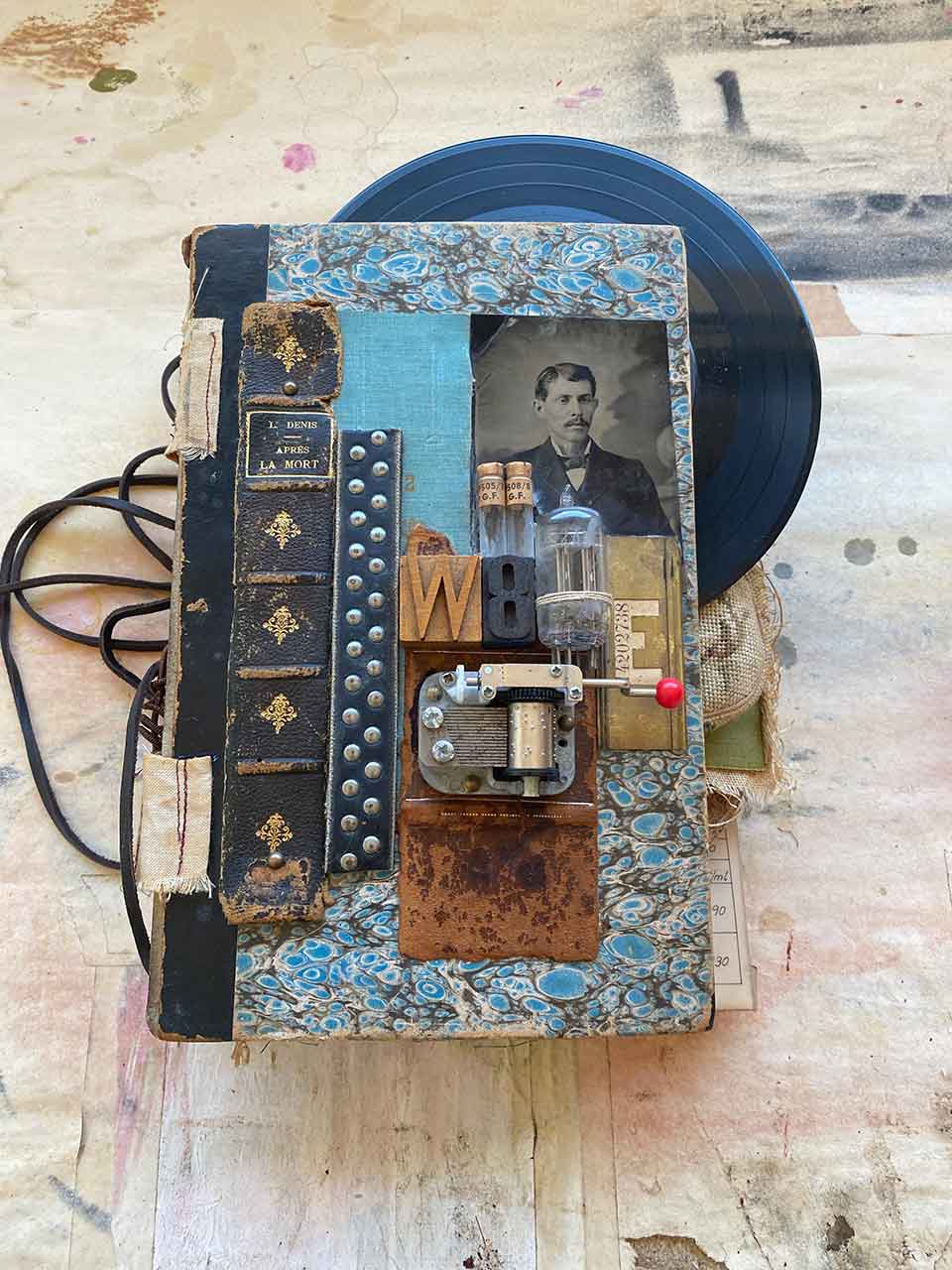

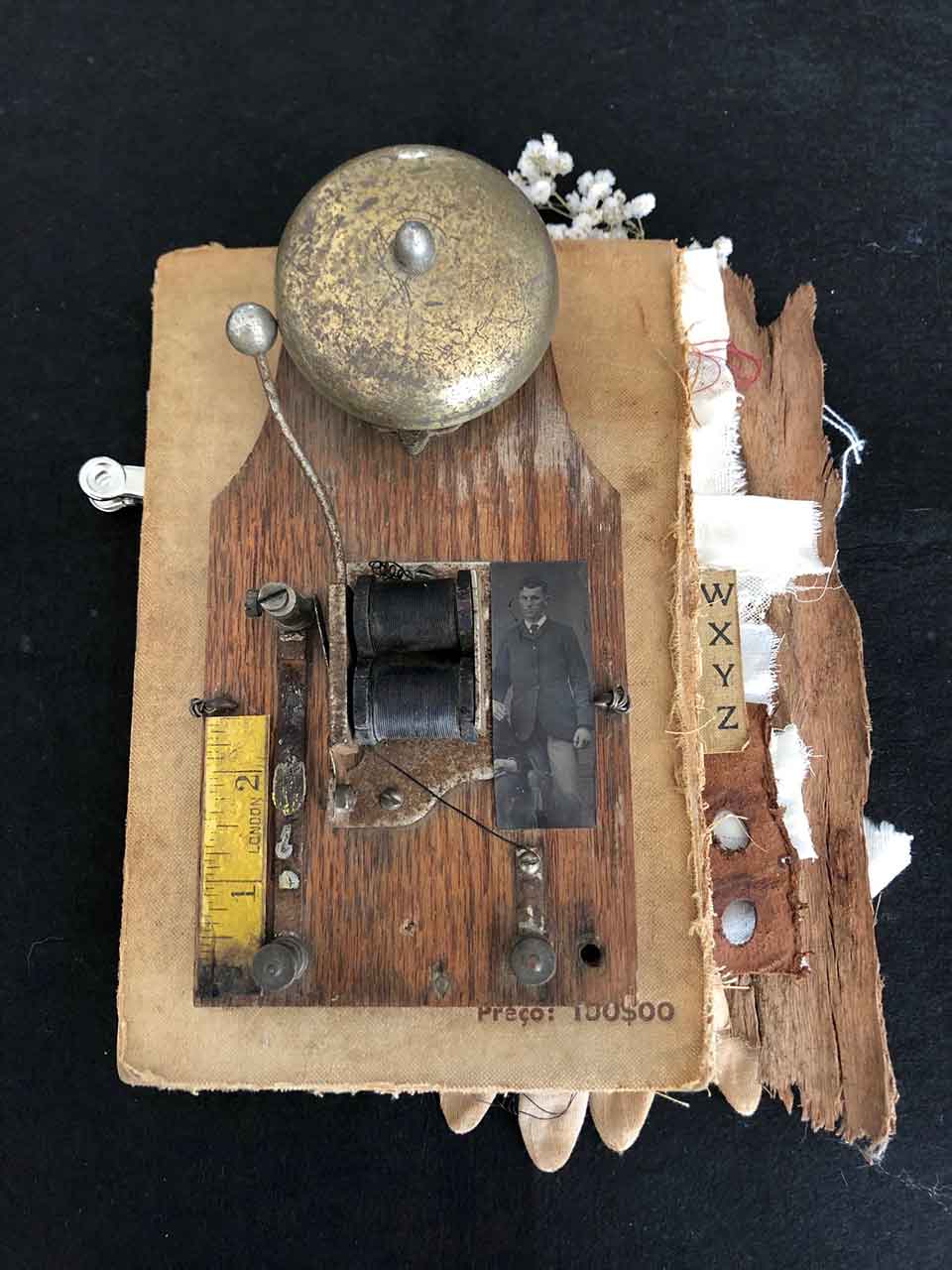

Some book-saving initiatives are respectful of form, content, and use, and some change one or all. After one century of mass production revolutionized the volume, cycle, price, and lifespan of book production, the digital revolution has opened endless possibilities. From selling used or discarded books online to creating worldwide digital book archives, a revolution in attitude has occurred. Reverence for physical copies is out, playful initiatives are in. Adding artistic or whimsical elements and deconstructing books give another visual dimension to the written word and multiply the ways in which it can be seen and read, understood and used.

A modern reverse ekphrasis is repurposing book form and content with bewildering creativity.

We have come a long way from the early repurposing of leather spines, gold lettering, and gilded pages stuffed with empty blocks filling nouveau riche bookshelves. A modern reverse ekphrasis is repurposing book form and content with bewildering creativity. From DIY enthusiasts to renowned artists, aesthetic surgery repurposes pages into paper cups, saucers, wall art, or containers for flora sculptures. Laurent Niclot and Kailee Bosch’s teapots made of laminated book pages pressed between turned wood pieces inspire a new reflection on the term “vessels of knowledge.” UK-based Maisie Matilda draws gorgeous paintings on the edges of hardcover books, creating “magical-feeling settings” for the books. Isobelle Ouzman creates altered book sculptures from hardback novels, journals, and notebooks, creating “a mix of illustrated and carved sculptures” with dreamlike visual scenes, prolonging the storytelling in a fairytale genre. New York–based artist Brian Dettmer cuts into old books to create remixed works of art, carving around whatever he finds interesting. LA-based Mike Stilkey uses stacks of old books as his canvases to make small portraits and giant sculptural installations, and often paints in the margins of books. A spectacular version of the book stack concept is Matej Kren’s Idiom book tower. This trend was even featured on the front page of the American Historical Association’s February 2023 Perspectives. There is a lot to learn from giving books and readers a second chance to rethink literacy. The proliferation of multispatial, multiuse books raises a question, however: Will future generations no longer know how to turn pages (in the way prescribed by their native traditions), the way they no longer know how to read time on analog watches? Will the digital age find an Esperanto format for books?

There is a lot to learn from giving books and readers a second chance to rethink literacy.

Turning to the “real” preservation of books, everyone can name private or state foundations with unique collections, from the Mazarin Library in Paris to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello; everyone has a favorite antiquarian bookstore or knows private book collectors, from the proud owners of priceless ancient copies to the managers of more democratic collections, such as Alberto Manguel. But these are local and have limited circulation. The real book preservation today is digital and global. UNESCO’s World Book Capital Network, launched digitally in the fall of 2022, is committed to encouraging literacy, lifelong learning, and freedom of expression. A collaborative project with worldwide partner organizations created the World Digital Library to which all major national libraries have access. Its descriptive metadata of world libraries’ holdings is available in seven languages including English. It features prominently on the home page of the Library of Congress and includes downloadable maps, texts, photographs, movies, and music as well as conference videos, podcasts, and museum artifacts and exhibits. Several bookstores such as the French FNAC now offer free downloadable book selections.

Open access works hand in hand with preservation to lessen the concern about book damage and book loss and to enlist books in a global cultural exchange. This in turn is changing the settings of libraries away from traditional on-site consultation or checking-out activities. National or municipal libraries increasingly offer a broader range of and settings for book consumption. Areas reserved for young readers have perhaps seen the greatest transformation since the 1960s. All these are signs of the democratization of book consumption. In Helsinki, Finland, the Oodi Library offers space not just for every reader—open spaces for group readings, womblike, intimate children’s stations—but also industrial-looking cataloging and shelving spaces for prereading and digital stations for postreading, scanning, copying, online surfing, and creative writing. Book users may confidently “sail” into the future of book culture and experience the shrinking distance between book consumption and creation.

How do we know which books to keep? Before we can answer this, we must look at the book industry and know who decides what is worth publishing. Authors, agents, publishers, editors, publicists, and primary receptors such as libraries, critics, and book clubs have long formed inevitable and necessary creative nebulae. At one end of the spectrum are creators like the Japanese poet Shizue Ogawa and the French author/artist Serge Chamchinov who create first and then self-promote. At the other end are mega-publishing houses that, whether driven by gambling or passion, engage in dizzying games of acquisitions and mergers, fight book rights in court, reinvent book genres and publicity, and manipulate authors’ texts into formulaic, success-driven productions.

The digital revolution has democratized what gets published by enabling the creation of virtual audiences.

Yet increasingly, here again, the digital revolution has democratized what gets published by enabling the creation of virtual audiences. The newest readers/authors nebula of #BookTok brings new life to overlooked books such as Lloyd Devereux Richards’s 2012 mystery novel Stone Maidens, which reached the top of Amazon’s best-seller list two weeks after his daughter posted a seventeen-second TikTok video. Other tight-knit book communities such as the California-based Point Reyes indie bookstore, writers’ groups, and state branches of the National Endowment for the Humanities help propel titles to fame and show that people still love to read.

Given this changed landscape, how do we choose which books to keep, and how do we anoint the classics of tomorrow? By their shelf life? By their international or blockbuster reputation? By their timeless message about the human condition, if one can define it? Will we keep slow-emerging gems such as Andrzej Sapkowski’s eight-volume The Witcher series, which was recently made into a successful movie after languishing for decades? This is not a new conundrum; digital technology has an expiration date and at some point in the future will have to be weeded out by concerns for its “sustainability” and “growth.”

Scottish artist Katie Paterson’s latest project answers these questions in a most unusual way. Conceived in 2014 as an art project, the Future Library is now being built entirely of wood in Oslo, Norway. Each year, for one hundred years, the project’s trustees invite one young yet internationally known author to submit a new, unpublished manuscript that they store in special drawers. The one hundred books are to be published in 2114 from a Future Library Forest of one thousand trees that have been planted to replace the wood used to build the library housing the manuscripts. The authors are selected for their ability to “capture the imagination of this and future generations.” The delayed consumption stimulates a new kind of literacy by forcing interested individuals to read “the rest of” these author’ works, to reflect on their staying power over time, to value the environment, and to think of a sustainable culture that embeds literature into art. The first nine writers and poets already chosen from Europe, Asia, and Africa, can be identified online.

O let me count the way we love books: as consumers and as co-creators, alone or in groups; reading, listening, watching; through word, still image, sound, or moving images; as merchandisers, producers, commentators, critics, or protectors; as recyclers, as destroyers, as worshippers. At home or in bookstores, at book clubs, libraries, little free libraries, passers of books through book reviews, teaching, or simply as gifts, in movie theaters, at literary evenings and book festivals, through podcasts, radio programs. There is no monotony in the book world. Books and their extensions—online versions, graphic versions—generate a web of words and affirm identities in freely shared exchanges. This emerging peri-culture broadens and democratizes the educational value of books. Most importantly, by creating book communities, readers know they are not alone. Books are part of our landscape, they become our palimpsests as we learn to recognize the “hero with a thousand faces” and to create resonances between ourselves and the books we read.

Most importantly, by creating book communities, readers know they are not alone.

Besides encouraging literacy, another very important mission for books became clear following the massive cultural destructions of World War II. From the beloved Parisian bouquinistes to the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, memorializing human culture has been valued. ILAB was founded in 1947 by Denmark, France, the UK, the Netherlands, and Sweden to open book markets in order to foster international peace, friendship, and understanding in the early days of the Cold War. Since then, preserving books has been a political and civic decision. Today there are twenty-two national antiquarian booksellers’ associations working in thirty-seven countries and over 1,600 individual affiliates worldwide. ILAB not only promotes standards in the trade but fosters a broader appreciation of the history and art of the book.

What emerges from this tour d’horizon is that all keepers of the book have common goals: advancing peace, freedom, lifelong literacy in a new digital Tower of Babel; recognizing that communication among nations is important to promote tolerance and democratic values; documenting the history of the printed word; encouraging identity formation and awareness individually and collectively. Enhancing the great diversity of modes of humanistic expression through time is a proven way to encourage cultural enrichment and progress. May book culture remain alive and well, and long life to the keepers of the books!

University of Tennessee at Martin