Repairing the Breach: A Conversation about Reparations with Marcus Anthony Hunter

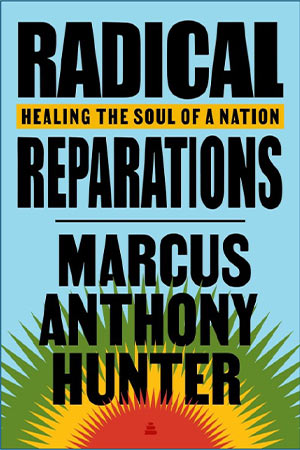

The idea of reparations for slavery—a polarizing topic—continues to gain traction in US society. According to a 2023 Pew Research Center survey, 18 percent of Americans now support reparations, a significant increase since 2000, when only 4 percent were in favor. To date, the state of California and more than a dozen American cities have created reparations commissions or programs aimed at ameliorating the effects of historical racism. With his recent book Radical Reparations: Healing the Soul of a Nation (HarperCollins, 2024), UCLA sociologist and Black Studies professor Marcus Anthony Hunter has produced a manifesto for the burgeoning movement, aimed at those who assert that it is impossible to assess the cumulative effects of slavery and therefore provide commensurate restitution. Radical Reparations offers seven broad areas of repair for the historical harms and present-day legacies of African enslavement and Native dispossession. In my recent conversation with Dr. Hunter, I asked him to explain what he means by radical reparations and why it is that we need them if we are going to authentically heal the American soul.

Karlos K. Hill: Your current work is not only thought-provoking, it’s also very timely. Can you help us understand why you see focusing on loving Black people, caring for Black people, as key to healing the soul of this country?

Marcus Anthony Hunter: People today are fed a steady diet of misinformation, especially about Black people and human hierarchy, but I didn’t grow up like that. I came from a background that was deeply Black. In fact, I grew up in an extremely blackity-Black household. My parents were fans of anyone who was Black and succeeding or doing something, and they filled our house with Black music, from folk bands to R&B to pop. I am really fortunate to have come from that vibration of Blackness into the world, and I carry it with me everywhere I go. In my opinion, much of what keeps us back and blocks us spiritually, materially, and financially comes not from white people but from things amongst ourselves. In “Art and Such,” Zora Neale Hurston said—and I’m paraphrasing really terribly—“Black people have a thousand and one interests. Only one of them is what white people are doing and saying.” So I’m really curious about the other thousand: What are we doing and saying? The community I was raised in wasn’t impaired only by things like government policies but also by how we were with each other—our boundaries, our hierarchies, our food chain. So I want to pour light and possibility and imagination and love into that space, because I think it badly needs it. And it deserves it.

Hill: You dedicated your most recent book, Radical Reparations, to the late legal scholar and activist Derrick Bell. Can you explain his importance to this book and why you chose him as the dedicatee?

Hunter: I think of Derrick Bell the same way I think of W. E. B. Du Bois. I never met either of them, but through their contributions as intellectual scholars and activists, they have been great teachers for me. I started out knowing only a little bit about Bell, but as I became more familiar with him and his work, I discovered a lineage of sorts of Black law professors who were impacted by him. Among that group are Kimberlé Crenshaw, Cheryl Harris, and Devon Carbado at UCLA, so when I got there and was able to meet them, I asked them to tell me about him. Despite their different relational fields, they all had really positive things to say. And the way they talked about him brought him to life for me, so that I was able to see him as a real person, a teacher, someone who cared for people and affirmed them and challenged them.

For Cheryl Harris, one of Bell’s most important contributions was that he freed up the legal form by reintroducing story. As Black people, we come from a griot tradition. Storytelling comes naturally to us, but in writing and communicating our ideas or our findings as legal scholars, we’re not allowed to tell stories. In her description, Bell tore down a metaphysical barrier, a professional barrier, an industry barrier. When I went back to his work with that kind of lens, I was amazed. His book Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism was my inspiration and blueprint for Radical Reparations. If this legal genius is telling us that racism is permanent, why are we operating like it’s something we can simply move on from? Why do our minds work like that?

Black people aren’t of one mind about reparations, but it is a resource-driven conversation. If that resource were to come our way, what could I do to help unlock and unblock others’ minds about it so that we could envision solutions for our community that we could agree on? Obviously, no amount of money could balance out the debt that is owed, but it seems like economic reparations are all we hear about. What about political reparations, intellectual reparations, legal reparations, and spatial, spiritual, and social reparations? When reparations are reduced to a matter of dollars, we end up being deprived of the opportunity to arrive at our own destinations, for our own communities, for our own well-being, to decide what kind of repair is due to us, so that we can heal ourselves and then heal a nation that is accountable for the disrepair we’ve experienced.

What about political reparations, intellectual reparations, legal reparations, and spatial, spiritual, and social reparations?

Hill: You’ve done a lot of work with US Representative Barbara Lee as part of the push for reparations in California. How did you get involved with this movement? And how does that work connect, if at all, to the book?

Hunter: Congresswoman Lee called me out of the blue one day. A panel on slavery I took part in at the LA Times Book Festival had aired on C-SPAN Book TV, and she was calling to praise me for the job I did. She told me she was introducing legislation to establish a US Commission on Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation, and she wondered if I would be interested in helping.

Fast-forward six years, and we’re still working on it. The legislation we drafted was introduced in 2020, and since then we’ve worked with a number of wonderful people and organizations, including Prophet and the Black Music Action Coalition, David Johns and the National Black Justice Coalition, Dreisen Heath and the “Why We Can’t Wait” campaign, Ron Daniels and NAARC, and Kennis Henry and N’COBRA. A lot of groups were organized as this started to unfold, because the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor galvanized the public in a way we hadn’t seen before.

As a result of that one call from Barbara Lee, I found myself participating in Zoom calls and work groups, meeting with members of Congress, and learning how our legislative system works, all while continuing my research on reparative justice and its history across the world. How policy folks and activists and legislators work and think is different from how professors and academics work and think, and it all started to overlap in my mind in ways that made me realize I had an opportunity to weave these things together for others so that they would have a combined resource they could go to. I didn’t want people to feel like they should have done their homework before they encountered these concepts. The only thing you need to bring to this conversation is shared humanity, because anything having to do with racial equity, anything Black people have ever asked for, anything related to reparative justice, is genuinely a human request.

Multiple congressional leaders, led by Rep. Lee, have been working with the current administration to get from them in the last sixty days what we asked them for in the first hundred days, which is an executive order to establish a truth and reparations commission, so that we can bring together the nation’s leading figures and give some advocacy to an infrastructure of love and legislative policy that could transform our current existence.

Hill: In addition to Derrick Bell, is there anyone else you’d want to acknowledge as an inspiration for the book?

Hunter: The book was actually dedicated to five people. The others are my dad, Marcus Allen Hunter, who died of a heart attack on Labor Day in 2020; one of my oldest friends, and someone who taught me the power of love through friendship, Medina Johnson, who died in June 2021, before her fortieth birthday; one of the most important Black male teachers I ever had, Manning Marable, who also died early; and the science fiction writer Octavia Butler, whose Parable of the Sower was part of the foundation for Radical Reparations alongside Derrick Bell’s work.

The first chapter of Butler’s book opens with “All that you touch you change. All that you change changes you. The only lasting truth is change. God is change.” As I work through this process of reparative justice, I offer up a remix of my own, the Reparations Parable: “All that you repair you heal. All that you heal heals you. The only lasting truth is love. God is love.” For me, the biggest takeaway from what Butler talks about in her book is that slavery, both as an idea and as a practice, not only defames the humanity of Black Africans but also creates a breach in the soul of who we are as human beings. There’s a spiritual authorization that reverberates across the world when you decide that there are large populations who are not human. So until that breach is repaired, we will never be able to succeed.

There’s a spiritual authorization that reverberates across the world when you decide that there are large populations who are not human.

I think we only have one real chance to have this conversation and see something happen, and it will require that all of us feel that we have a role in the process and a stake in the outcome.

Hill: Have you given any thought to how you would ideally like your book to live in the world?

Hill: Have you given any thought to how you would ideally like your book to live in the world?

Hunter: There is a well-known quote from Audre Lorde, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” I’ve seen various analyses of it, but my own reading of the sentence is that the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house because the master didn’t build his house. The master owned slaves, and it was those slaves who built the house. This interpretation gives us permission to reorient ourselves to the story of ourselves, to the idea that racism has workers behind it who have built up a wall, and rather than focus on tearing down that wall, because in some cases they made us build it, they tell us we can build something else. I would caution against a pure focus on dismantling things if we aren’t also building at the same time. If we could build an infrastructure of love, I don’t think we’d be talking about hate. If we could build an infrastructure of systemic equity, we wouldn’t have to focus on inequity.

But we haven’t been building, and that’s where we’re getting lost. So I want this book to be an invitation to build. I want it to be the first block in building something positive. A therapist once told me, “I’m not going to say that what you feel to be your bad habits or bad behaviors or traumas are somehow going to be removed from you. That’s not going to happen. What I can help you do is seed, water, and nurture something positive, and eventually those other things will be dwarfed by its presence.” It’s not like we can just uproot everything, then look to the right and see everything already built. So, I wanted to write a book that would encourage people to take up the tools and resources available to them, to help them see that healing isn’t just a concept, it’s an experience.

Hill: You’ve given me a better understanding of the depth of this work, how layered it is, and how it can speak to people spiritually. But I also have a better sense now of the practices you’ve learned along the way and were able to instill into the text. Beyond the framework you’ve provided for helping people grapple with the various ramifications of restitution, how would you envision an America that has been healed as a result of some of the things in your book?

Hunter: I see peace of mind. I see dramatically fewer people un-aliving themselves. I see dramatic declines in anxiety and stress, dramatic declines in criminal behavior and gun violence, dramatic declines in poverty. I see increased development of new forms of rehabilitation, whether they be for addiction to substances or addictions to criminal behavior. I see a society with less debt, greater educational attainment, and increased generational wealth. I see people reporting more happiness, more hope, more optimism. Those would be the indicators that we’re in a healed place.

Hill: Are you saying that the inherent promise in healing the soul of the nation is a revolutionary change in how we relate to one another, and perhaps to ourselves?

Hunter: It’s revolutionary in the sense that there’s a movement underway, but the most important thing is that we can become something that all of us actually want. Everybody longs for something that would be different from what we currently have; we all seem to have that desire in common, even if we don’t agree on the best way to get there. When we think about an issue like slavery, it almost seems untouchable—and if people do want to touch it, they don’t want to touch it for very long.

What if we could hold onto that and integrate it into the very nature of who we are as a country, who we are as a world, and simply accept it? When a drug addict finally gets clean, one of their first steps is to lean into the fact of who they are and say, “I am an addict”—not “I used to be an addict” or “That was my past but I’m over it,” but “I am an addict. This is something I am constantly managing, every single day.” The ability to say that is what unlocks the pathway to their new life. You can’t become your best self if you remain in denial of the thing you now want to move beyond. Until we embrace that contradiction, we won’t be able to tap into the true potential of what it can unlock for us. That, to me, is where the true power is.

November 2024

Marcus Anthony Hunter is the Scott Waugh Endowed Chair in the Social Sciences Division and professor of Sociology & African American Studies at UCLA. Dr. Hunter drafted and advised Congresswoman Barbara Lee’s historic bill to establish the first-ever US Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation Commission.