Almaty, Kazakhstan

In Almaty, people read everywhere, bookstores are plentiful, and the Kazakh language, engaged in a “lingual fracas” with Russian, is reasserting itself.

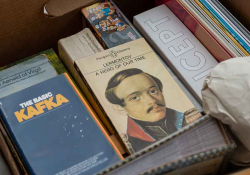

In central Almaty, in a leafy park off Gogol Street, an old man held two thick books in one hand, while his other—open and palm upward—rose and fell with the weight of a phantom donation. The two books were Russian, their black hardcovers inlaid with golden Cyrillic lettering. I told him, in a faltering Russian of my own design, that I didn’t read the language. “Man-ay! Man-ay!” he insisted, not aggressive but laughing kindly. I gave him the tenge coins in my pocket and let him keep the books. There were plenty more to be had, in nearby Меломан (Meloman)—which besides crisp new books printed in Russian, Kazakh, and English sells ice cream, vacuum cleaners, electronics, and other household paraphernalia—or in Bouquiniste, the best kind of secondhand store, smelling of earthy vanilla, with books on the floor and plenty of obscure titles to rootle through.

In Almaty, you see people reading everywhere—on park benches, in the many cafés, while on the metro, or stuck in the appalling traffic. Russian books are the most common: it is the lingua franca of the Central Asian, ex-Soviet bloc, and, though it and the Kazakh language bear few similarities, many Kazakhs across the country—even the youth—still use it, and not their native Kazakh tongue, to communicate. Yet Kazakhstan is today riding a surge of nationalistic pride, slipping out from under the shadow of its colonizing nation, becoming rich on its natural resources, and using that money to fund ethno-supportive endeavors: from sport (the 2024 Nomad Games, held in Astana, provided the opportunity to showcase not only the country’s modernized capital but its dominance in ethnosport) to scholarship (in 2021, the government sponsored Kazakh-language translations of one hundred international textbooks to be used in school across the country).

The Kazakh language itself is being reassessed, with its alphabet now in the process of replacing Cyrillic lettering with Latin.

And the Kazakh language itself is being reassessed (one could say decolonized), with its alphabet now in the process of replacing Cyrillic lettering with Latin. Thus, кітап (book) becomes kitap, өлең (poem) becomes öleñ, and so forth. The process, meant to be completed by 2031, will be the fourth iteration of the alphabet. The originating languages of the region—Old Turkic and Mongolic—were first carved into rocks in runic figures. When Islam arrived in the eighth century, so did Arabic script, and since the arrival of the Russian Empire in the 1800s, Cyrillic has taken over the nation’s written form, albeit with forty-two letters over the Russian thirty-three, to accommodate Kazakh intonation.

These changes in Kazakh writing are reflected in its literature through W. B. Yeats’s famous phrase, “We make out of the quarrel with others, rhetoric, but of the quarrel with ourselves, poetry.” The quarrel is interior, one of marrying mythology with modernism, the rural village, the aul, with the ultramodern aspirations of Astana and Almaty, the Russian nostalgia with traditional folklore; the art most readily tackling the lingual push and pull is that latter form.

Poetry has been a part of Kazakh culture since the times of nomads and khanates, when aqyns, oral storytellers, were the conduit of the nation’s mythic past. But historic enthusiasms must be tempered with modern realities. The act is in part generational. Those younger individuals who grew up speaking both languages can find themselves pressed between the two tongues, able to fully express themselves only by continuing to speak both. What the poet Anura Duisenbinov calls “tilечь” (a portmanteau of the Kazakh til and the Russian речь, both of which mean “speech”) is a theme encountered repeatedly in Kazakh poetry, such as in Tumanbay Moldagaliyev’s poem “Mother Tongue,” in which he tells his son: “Understand / my language which is yours and take / my Kazakh heart. The rest is up to you.”

I discussed this with Alisa Ganieva, a Russian author who has lived in Almaty since 2022. In a café surrounded by Russian speakers, discussing books—her Dagestan-set novels—and the thorny business of Moscovian publishing, she said: “Even here, next to Kyrgyzstan, to China, we’re still closer to Russia in so many ways.” She said she would start learning Kazakh soon; not an easy task, but as a native Avar-speaker from Dagestan (which has some forty endemic languages), she understands the importance of integrating into a linguistic identity.

When I asked about Kazakh literature, Ganieva pointed me to Duisenbinov, Moldagaliyev, and other poets who are entangled in the lingual fracas. As it deals with its internal changes, Kazakh literature has been slow in its international presentation into English. The most ready example is the Contemporary Kazakh Literature Poetry Anthology (2019), a collection of thirty-one poets that includes many existential poems on the subject of the Kazakh language. The continued presence of Russian is sometime felt like a hot knife against the skin, as in Aliya Dauletbayeva’s “The Language of Abaj”:

Brought up in a foreign land

I cannot speak of it without anger,

Back then, I lived like an orphan

trying in vain to find his mother.

Abaj Ķůnanbajůly, Kazakhstan’s preeminent aqyn, is there, waiting to be received and absorbed in Kazakh, if only Dauletbayeva could access him as easily in that language as in the Russian she was raised to speak. Russian (especially within the Soviet system) was so pervasive, so obfuscating, that today’s dual wielding of these languages puts a turn on the classic phrase and makes home, rather than the past, the more foreign country. As usual, the quarrel with ourselves yields more poetry than answers.

I finished my days in Almaty wandering the clean, wide streets and visiting the nearby mountains that stand blurred by the smog which hangs over the city. When I left the country for Kyrgyzstan, I went by train. We crossed late at night, and while waiting for the border guards, I sat in my cabin drinking whisky and reading the Kazakh Anthology. When the guard appeared to stamp me out of the country, he noted the book, and the others on my table—Sebald, Nabokov, Pushkin, Silvestre. I feared the worst, but he only said, “Я люблю Джак Лондон.” I like Jack London.

Gladstone, Manitoba