Bordeaux

In December 1801 the poet Friedrich Hölderlin accepted a position as tutor at the Bordeaux residence of German wine merchant Daniel Christoph Meyer. For reasons unknown, he walked the six hundred miles from his home in Nürtingen, Germany, to his new appointment, shivering over the mountains and sleeping on the ground with a loaded pistol in his hand.

Fewer than a dozen documents make note of Hölderlin’s French sojourn. One was his poem “Andenken” (Remembrance), in which he captures the loneliness he felt in Bordeaux, his confusion, his lovesickness, his desire to “speak the thoughts of the heart, / And to hear much of days of love, / And of deeds that occur.” What deeds occurred during Hölderlin’s time in France is unclear, but it proved to be a pivotal turning point for the young man. The cloak of madness was approaching, and he left only three months later, walking back to Germany and eventual internment at a psychiatric clinic.

Hölderlin lost his sense of life. Things slipped away from him.

I arrived to Bordeaux in darkness, the rain slapping the windows of the train. The Garonne split the city in two, a creaseless ribbon of brown under the fuzzy lights of the Pont de Pierre. I walked through the downpour to my hotel, where the halls smelled like a vet clinic, and fell asleep to the sound of water rushing through a drainpipe.

What might have made for a gloomy visit was not so bad, for, come morning, I had what Hölderlin lacked: companionship, conversation, and ardor. The rain carried through to morning, the sky as flat and gray as the bottom of a cast-iron pan, but mon amie and I took our cue from Stendhal, who, though he visited in rain so heavy it crumpled his umbrella, considered Bordeaux a city “where one thinks only of living well.”

In France, living well is sensory: visual (women’s eyes penciled like Egyptian ankhs), auditory (the generous use of Madame and Monsieur), and gustatory, which for us meant good coffee, croissants that pulled apart like honeycomb, and the local wine, both hard and smooth, like an iron fist in a velvet glove. Henry James, a heavy boozer, said Bordeaux was “dedicated to Bacchus in the most discreet form.” Like him, we occupied ourselves with a search for good claret from “the bright, cheerful, smokeless industry,” but we drank more plonk than Pauillac.

Between meals, we walked along the wide river camber upon which Bordeaux is built. This curve gave the city the alias the Port of the Moon. Bordeaux-born painter Pierre Lacour turned his eye on the riverside, as did Édouard Manet, both capturing the busyness of the Garonne; Lacour’s neoclassic Vue d’une partie du port . . . looks upriver, while Manet’s realist The Port of Bordeaux looks down, the twin peaks of the Saint-André Cathedral rising behind a forest of boat masts. We visited the Saint-André, and the Basilica Saint-Michel, both sheathed in scaffolding, both cavernous and cold.

Evening fell. The brass-covered lights strung over the streets pulsed dimly. Above us were the narrow balconies of urban homes, thin rectangles of warmth, framed by wooden shutters. One cannot help but feel there is good life there, although one can only see perhaps the leaves of a plant or the top shelf of a bookcase. But it is not about what one can see as much as what one can sense.

We supped at Le Vieux Chaudron, a fissure of untreated stone just up from the Grosse Cloche, with an inauspicious facsimile of The Last Supper hung above the bar. French restaurants have a tumbling quality, with the energy of both a grand opening and closing day. The cuisine may be known for its refinement, but the meals in Bordeaux had a heaped, everything-must-go form. I was beaming over my duck gizzard salad and beef tartare with raw egg yolk. “They forgot to cook your food!” my amoureuse said, guarding her goat’s cheese and turkey breast avec frites.

Leaving the restaurant, the rain had eased. The air smelled of graphite and leaves. We strolled arm in arm back across the Garonne. It was nothing like Hölderlin’s six hundred miles, but it was a turning point nonetheless. A shift toward living well. What precipitated the change? To paraphrase Bordeaux’s erstwhile mayor Michel de Montaigne, “Parce que c’était elle, parce que c’était moi.”

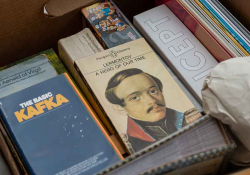

Head to Bradley’s Bookshop for new English books, Quai des Livres for French, and La Nuit des Rois and Au Petit Coin for used.

What to Read with a Glass of Claret

Soledad Puértolas

Bordeaux

Trans. Francisca González-Arias

University of Nebraska Press

Jean-Pierre Alaux & Noël Balen

Treachery in Bordeaux

Trans. Anne Trager

Le French Book

Alcide Bontou

La cuisinière bordelaise

Editions De Borée

Stendhal

Travels in the South of France

Trans. Elisabeth Abbott

Alma Classics

David Mandessi Diop

Hammer Blows

Trans. Frank Jones

Indiana University Press