Best Actor

Reflecting on his love of football, Oliverio Coelho has an epiphany: some players on the pitch stand out, not just for their skill, but their intelligence, and it is these players that establish the beat for the expression of political solidarity that, in these difficult times, is the ultimate goal.

I can’t say precisely what it was that, for decades, I so enjoyed about football. I regard myself as a generally unemotional person, with the odd exception—adolescence, for instance—but an attentive observer. At first, perhaps, it was because I went to almost all the stadia of Buenos Aires with my father in the 1980s and ’90s. Going to the football match was an activity we could do together. Afternoons at the match had a distinctive quality: the smell of choripán sausage sandwiches and burgers, the inchoate chanting from the stands, the flags, the deafening firecrackers, the drums, and quasicriminal groups of lumpen youth who would invariably end up entangled with the mounted police.

Today I watch football and see it more as a chessboard, an arena for class warfare, arithmetic, the golden ratio, immigration, xenophobia, skill, and, every now and again, the odd line of poetry uttered by a manager.

On the other hand, I know exactly what it is that attracts me now, something new and different from when I was young, when I watched with passion and not a cool, objective appreciation of, for instance, the elaborate roles played by the fullbacks at Guardiola’s Manchester City. Today I watch football and see it more as a chessboard, an arena for class warfare, arithmetic, the golden ratio, immigration, xenophobia, skill, and, every now and again, the odd line of poetry uttered by a manager. But above all, it’s a collective construct. This was proved by the Argentine national team at the Qatar World Cup. A flexible construct only possible in the apodictic territory of play. And so, at the age of forty-six, for me every game of football is now a performance: if it’s on TV, it’s like cinema; at the stadium, it’s a play.

This revelation began to dawn on me about a year ago, when my son and I were watching a rerun of the 1985 Intercontinental Cup final between Juventus and Argentinos Juniors in Tokyo. Connoisseurs claim that it was the most exciting final in living memory, which is to say that if there were an Oscar for the best game of the year, the ’85 Argentinos versus Juventus would take the statue. On one side were Michel Platini and Michael Laudrup. On the other, Bichi Borghi and Sergio Batista, who would the following year become world champions as part of the team led by Diego Maradona. That year, in Tokyo, they were competing in the best actor category.

Football is like an immaterial encyclopedia under constant revision. Every game, every corner kick, bears the imprint of how the world works and its future history.

I don’t know why it took me so long to learn the secret of football. It’s like an immaterial encyclopedia under constant revision. Every game, every corner kick, bears the imprint of how the world works and its future history. You don’t necessarily get to see that at the stadium. Or better put, you don’t necessarily get to see that in the cheaper seats at the Estadio Diego Armando Maradona, in the heart of the Paternal neighborhood between the streets of Boyacá, San Blas, Gavilán, and Juan Agustín García. Sitting in said seats is almost like being on the pitch; a strategic appreciation of the game is sacrificed for the thrill of being so close to the players.

However, in the upper tier of the stand that bears the name “Checho Batista”—in honor of the central midfielder who, even today, together with Fernando Redondo, another player who came up through the ranks of the Argentinos Juniors youth system, is considered the best-ever Argentine to have played in that position—one gets an excellent view of the game as a whole. It was in this tier that I had another footballing epiphany, before the one mentioned above: some players on the pitch stand out, not just for their skill, but their intelligence. Watching Juan Román Riquelme play in his retirement year in Paternal demonstrated to me the advantage this kind of player has: no longer able to run very fast, he made a difference because he always knew the exact positions of his teammates and opponents before he received the ball.

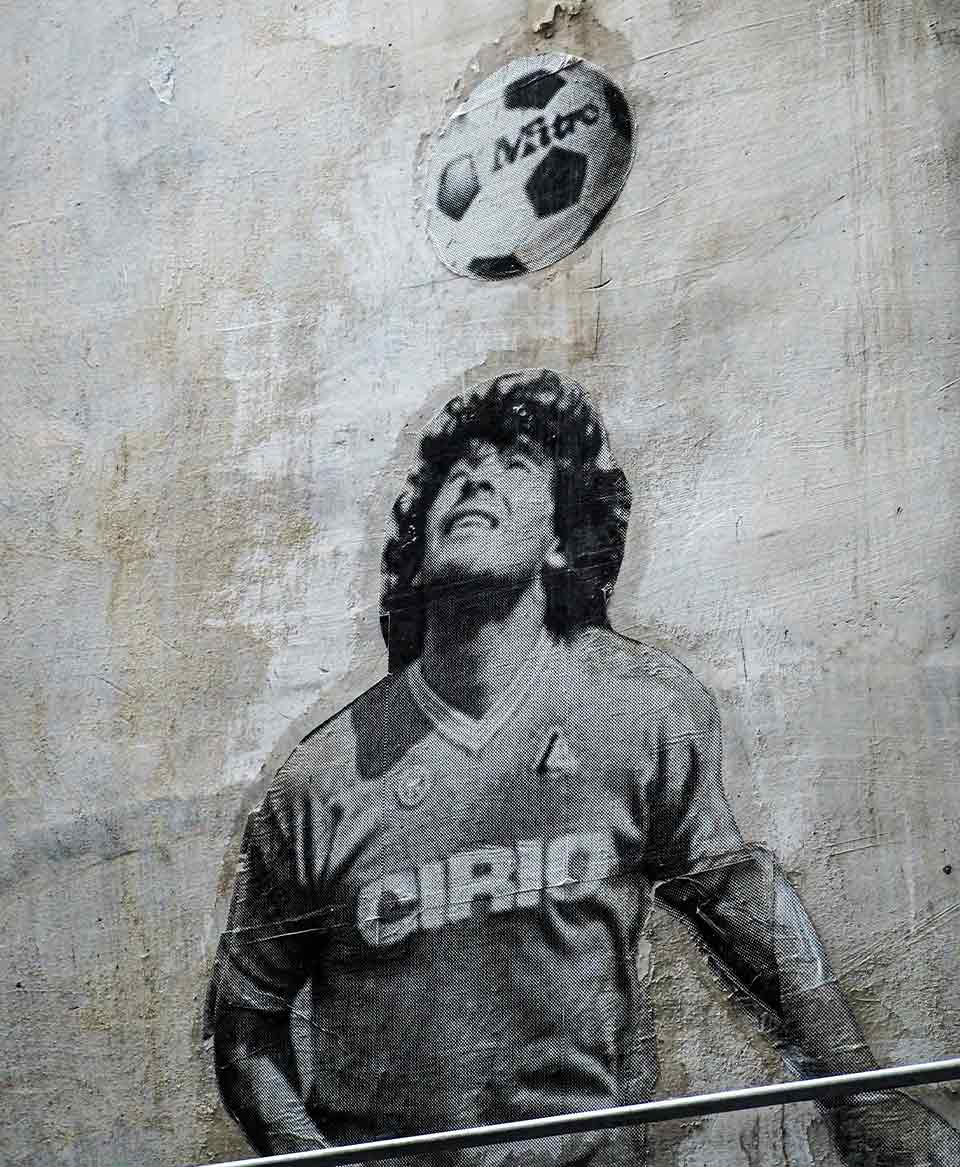

As a boy, when I watched Maradona play in a game between Argentina and Uruguay, I didn’t understand that difference. All I wanted from the genius was for him to show off his gifts: his tricks, swerving past players, scoring goals. I thought that genius meant flamboyance, and, on that night, Maradona wasn’t flamboyant, he was only efficient. The truth is that the player who makes a difference, the gift that can only be appreciated from higher up in the Checho Batista stand, is the one who can dominate and keep an image of the entire pitch in his mind, who can intuitively get the whole team playing the same tune. To a degree, they are the conductor who establishes the beat for the expression of political solidarity that, in these difficult times, is the ultimate goal.

Buenos Aires

Translation from the Spanish