Preserving Santa Monica’s Black Past: A Conversation with Carolyne and Bill Edwards

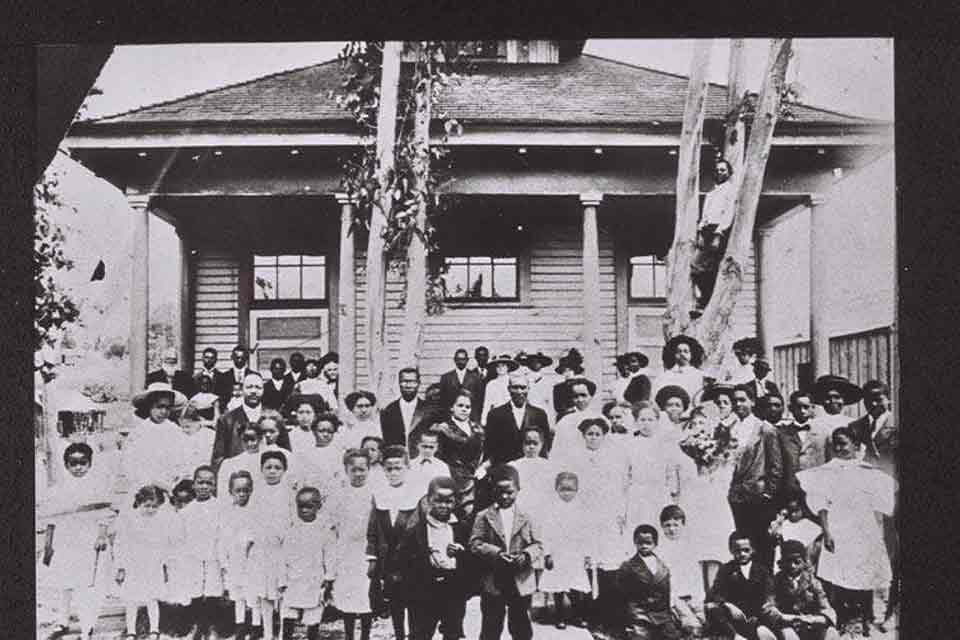

Bill and Carolyne Edwards met and married in Santa Monica’s Black community, where they continued to live until it was demolished in the 1960s to make way for the section of I-10 known as the Santa Monica Freeway. The rich Black history of this area is not well known, but Bill and Carolyne remember the varied and vibrant communities in the Belmar Triangle and Broadway neighborhoods. In 2019 the Edwardses created an educational archive, the Quinn Research Center, to preserve the forgotten history of Black Santa Monica. It was named for Dr. Alfred T. Quinn, a prominent Black educator, community leader, and bibliophile, who collected hundreds of photos, documents, and artifacts over the years that constitute the bulk of the holdings.

Santa Monica’s extensive Black history had been largely forgotten until the Quinn Research Center collaborated with the Santa Monica History Museum on a public history project titled Broadway to Freeway: Life and Times of a Vibrant Community. The resulting exhibition, which opened at the museum in April 2022, recalled the heyday of the once-thriving Black community that developed between 14th and 20th Streets on Broadway Avenue. Bill and Carolyne graciously shared with me their memories of living in Black Santa Monica in the period before the freeway came through and split the community apart, demolishing homes and businesses that had once been an integral part of the fabric of Black life there.

Karlos K. Hill: Few people in this country would associate Blackness with Santa Monica. And yet a prosperous Black community had developed in the city by the 1940s, only to be destroyed in the 1960s to make way for construction of the Santa Monica Freeway. When did your families first come to the Santa Monica area, and what was it like for them when they arrived?

Carolyne Edwards: My father, who was living in Fort Worth, Texas, at the time, came out to California in 1932 to see a cousin who was living in Los Angeles. The very first time he visited Santa Monica, he fell in love with it. He was so impressed with the climate and the community that he decided it was where he wanted to live. He went back to Fort Worth, packed up all his belongings, and came right back to California. It was in Santa Monica that he met my mother, whose father was a minister who had been assigned to the AME church at 19th and Michigan. Their four children—my brother and I and our twin sisters—were born in Santa Monica and raised there.

It was my father’s dream to own property in Santa Monica, and he worked hard to achieve it. —Carolyne Edwards

It was my father’s dream to own property in Santa Monica, and he worked hard to achieve it. He and my mother got help from the US government in the early 1940s, in the form of an FHA loan. The Black population was increasing in Santa Monica because of all the people coming from other parts of the United States to work at Douglas Aircraft, but there was a housing shortage, so the federal government gave five recipients grants of $50,000 each to build apartment units to be rented to African Americans. My parents were awarded one of those five grants. They built three single-unit apartments originally, then added three more in the 1950s. Those six units are still there. Before my father passed, he expressed to us his strong desire that we would never sell the land or the property.

Hill: Why did that property mean so much to your father?

Carolyne Edwards: He worked hard to accumulate enough cash or capital to purchase it. At one point he was working three jobs. Plus he knew that it was prime property. We lived there in one of those apartment units until the early 1950s, and then my parents were able to use the additional rental income to buy a home south of Pico. Back then, it was unheard of for African Americans to even think about crossing Pico. But they were able to purchase a three-bedroom home on Hill Street.

In those days, when you heard of a property that was being sold, you could knock on the door and ask about it. And that’s what they did. They knocked, and when the people who owned the place came to the door, it turned out that they were African Americans who were passing as white, and it just so happened that they knew my mother through one of their daughters. So it was a bit of a fluke that my parents were able to buy the property where we were raised. When we first moved there, there was a lot of hostility. My mother and father were called the N-word. But after a while, things kind of settled down. People got used to seeing us and recognized that we weren’t going to somehow bring down the neighborhood or lower their property values.

Hill: Could you share some of your favorite memories of your years in Santa Monica?

Carolyne Edwards: The area I grew up in on Virginia Avenue in the Pico neighborhood was a mixed community. There were African American, Mexican American, Japanese, and white families. We played together, we went to school together, and we were all great friends. If there were racial overtones, I wasn’t aware of them. I’ve talked to other people who lived in the area at the time, and they said the same thing, that there were no racial problems between us. At one point, my sisters and I were the only African Americans in the school we were going to at the time, and even then I don’t remember having any difficulties. I have fond memories of the community and don’t feel as though I was subjected to a lot of prejudice. In junior high and high school, I always felt as though I was just as good as anyone else.

Hill: Bill, do any memories come to mind for you?

Bill Edwards: I didn’t grow up in Santa Monica. I grew up in East Texas, but I moved to California in 1955 or ’56 to live in West LA with my sister. Back then I didn’t know anything about the Pico neighborhood or that the city had even had a Black community. In 1964, though, I took a job with the Santa Monica school district, and that’s when I started learning more about Pico.

Not long after I moved to California, I took my sister up on her suggestion that I should take the bus downtown and look around. I was on Main Street, or maybe Broadway, and I was feeling hungry, so I went into a restaurant where there weren’t too many people inside. I sat down at the counter, and a white lady came over and sat down right beside me. I couldn’t help but get nervous, because that wasn’t something I was used to. In Texas, where I grew up, we had a segregated school out in the country. Everything we had there was hand-me-down, from the books to the football equipment, so I know what segregation is really like. And when I was in basic training during my time in the military, I saw how the white southern soldiers looked at us Black soldiers, even though we were in the same unit together. In Texas we knew what we could and couldn’t do.

So, when I came to California, it really opened my eyes about the race issue. Living and working in Santa Monica and seeing everybody get along was a great experience.

When I came to California, it really opened my eyes about the race issue. —Bill Edwards

Hill: As someone who lived in the Pico neighborhood before the Santa Monica Freeway came through, can you talk about the impact of its construction and the way it displaced people?

Carolyne Edwards: I remember my mother and father going to meetings about the freeway, and I’m sure they were worried that it would come through the area where we lived, but it didn’t have as big an impact for us as it did north of, say, Olympic. It mainly affected the merchants in the Broadway neighborhood, which was the hub of the African American community back then. That’s where all of the businesses were—the beauty shops and barbershops, the lodge hall, the social hall, many of the churches, the local mortuary, auto shops and restaurants and markets.

When I-10 went through the Olympic area, it wiped out hundreds of homes. The state and city gave those property owners some money, but it wasn’t enough for people to be able to buy another home in Santa Monica. So they had to take that little bit of money and go elsewhere, which ended up being Inglewood, Los Angeles, and even the San Fernando Valley. That took a lot of families out of Santa Monica, and then as the older generation started dying out, the younger generation whose families had been able to stay in the Black neighborhoods opted to sell their family property because the offers sounded so good. They chose to take that money and move to supposedly fancier neighborhoods. So the Black-owned homes in the Pico neighborhood were sold to other people who now have the rights to that land. I can’t tell you how many homes were sold on 19th Street alone.

There is a lot of industry now in the area where the 10 Freeway came through. Big corporations swooped in to buy that land and put up high-rise buildings. The land in the Belmar community where the county courthouses and the Rand Corporation are located used to belong to an African American man. I think they paid him less than $50,000 for the property where Rand now sits. All of the valuable pieces of downtown land that used to be owned by Black families are gone now. Developers gobbled it all up. That’s probably why my father was so adamant in asking us to please hold on to our family’s property. We get calls all the time from real estate people who want to buy it, and when we tell them it’s not for sale at any price, they can’t believe it. We’re holding on to it for future generations.

Bill Edwards: Many of the Blacks who are in Santa Monica now are renters. They aren’t Santa Monica natives who have any connection to the days when there was a thriving Black community here. They maybe don’t know about Broadway or what life was like before the freeway came through. They may have no idea that it was originally supposed to go down Venice Boulevard. That’s why Carolyne and I decided that we needed to do something to educate the younger generations, both Black and white, and show them what Santa Monica used to be like and how the freeway impacted it.

Hill: Is that how the exhibit Broadway to Freeway: Life and Times of a Vibrant Community came about?

Bill Edwards: We wanted to make sure that this knowledge could be passed down to later generations, so we got some of the older people to talk to us and share what they knew and remembered. It’s amazing that Blacks used to own so much property in Santa Monica, and the Black churches used to be full. There’s a lot of Black history here, a lot to be proud of, and a lot of Blacks aren’t familiar with it. We wanted to make sure it got told.

Carolyne Edwards: The exhibit began as a series of small events that just started evolving day by day. In 2017 or 2018 we had the good fortune of meeting a woman from Copenhagen who was spending six months in Santa Monica as a resident artist at the 18th Street Arts Center as part of a collaborative effort between the US government and the Danish government. We struck up a wonderful friendship with her. She told us that people in Europe put a lot of emphasis on the history, not just of buildings, but of cultures as well. That really struck a chord with us. We gave her a tour of Santa Monica. We showed her the apartments my parents built and took her on a tour of Broadway and the Belmar area—we went all over the city. We told her about various things that we remembered, and she was so intrigued that she incorporated them into her final project, an exhibition that was displayed at the Airport Campus of Santa Monica College.

That seemed to pique some interest locally. I then created a virtual PowerPoint presentation on Broadway for the Santa Monica History Museum, and the city brought in a historian who had done some work on the Belmar community. I was surprised to learn how many people had been under the assumption that Broadway was a spillover from Belmar; they didn’t even know that these were separate communities. We had amassed a lot of information on the area, including photos and a published listing from the 1950s of businesses in the Broadway community, so we talked to the History Museum about the possibility of an exhibition. We had a lot of materials to sort through, so it took a year to get it together, but it finally opened in April 2022. It was well attended and was selected for a Cultural Heritage Award by the Santa Monica Conservancy.

Hill: In Germany, the Holocaust remembrance community places special importance on making sure that there will always be visible reminders of the Nazi era so that future generations will never forget what happened there. The two of you have provided a valuable service in bearing witness to the destructive impact that the freeway construction had on the Black community in Santa Monica, raising awareness so that this history can be passed down from one generation to the next. And through your stewardship of the Quinn Research Center, you have made a treasure trove of information available to anyone in the community or beyond who wants to learn more about the city’s Black heritage more generally. By leaving these tangible reminders for those who will come after you, you have made it possible for others to continue the important work that you started.

July 2022